Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel was born near Morganfield in Union County, Kentucky, to John and Elizabeth McAllister Mitchel, who had moved there from Virginia. His father died when Ormsby was three years old.

|

| Union County, Kentucky |

|

| Lebanon, Ohio |

When I was a boy of twelve years, I was working for twenty five cents a week with an old lady, and I tell you I had my hands full; but I did my work faithfully. I used to cut wood, fetch water, make fires, and scrub and scour of mornings for the old lady before the real work of the day commenced; my clothes were bad, and I had no means for buying shoes, so was often barefooted. One morning I got through my work early, and the old lady, who thought I had not done, or was specially ill humored then, was displeased, scolded me, and said I was idle, and had not worked. I said I had; she called me ‘a liar.’ I felt my spirit rise indignantly against this, and, standing erect, I told her that she should never have the chance of applying the word to me again.

I walked out of the house, to re-enter it no more. I had no a cent in my pocket when I thus stepped out into the world. What do you think I did then, boys? I met a countryman with a team. I addressed him boldly and earnestly, and offered to drive the leader, if he would only take me on. He looked at me in surprise, but said he did not think I’d be of any use to him. ‘Oh, yes, I will,’ said I; ‘I can rub down and water your horses, and do many things for you if you will only let me try.’ He no longer objected. I got on the horse’s back. It was hard traveling, for the roads were deep, and we could only get on at the rate of twelve miles a day.

This was, however, my starting point. I went ahead after this. An independent spirit, and a steady, honest conduct, with what capacity God has given me have carried me successfully through the world.

|

| John McLean |

|

| Robert E. Lee |

Ormsby Mitchel graduated in 1829, ranked fifteenth in his class of forty-six cadets. After graduation, the Army assigned him to teach mathematics at West Point. While teaching, he met Mrs. Louisa Clark Trask, the young widow of a West Point graduate, with a son, Thomas, who had been born in 1828. Ormsby and Louisa married in 1831.

In 1831, he was reassigned to St. Augustine, Florida and served as a second lieutenant of artillery. Unhappy with military life, he studied law. While in Florida, the Mitchel's first child, Harriett, was born in 1832.

He was 50 years old when the Civil War began.

|

| Cincinnati, Ohio |

In 1833 Mitchel resigned his commission and moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. In Cincinnati, Mitchel passed the bar and became an attorney. Less than a year after becoming an attorney, Mitchel returned to teaching. In 1834, he accepted a position at Cincinnati College as a professor of mathematics, natural philosophy, and astronomy.

In 1836, he established "Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel’s Institute of Science and Language", located on the corner of Broadway and Third Street in Cincinnati. One of his students was George Hunt Pendleton, who became a "Peace Democrat" and Copperhead during the Civil War.

The Mitchels joined the church of Lyman Beecher, the father of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Mitchel became noted for his zeal at prayer meetings.

|

| Cincinnati College |

|

| George Hunt Pendleton |

The Mitchels had five more children while living in Cincinnati: Virginia, born in 1834; Louisa, born in 1836 (died in 1837); Edwin William, born in 1838; Louise, born in 1842; and Ormsby McKnight, born in 1843.

In 1836 and 1837, he also filled the office of Chief Engineer of the Little Miami Railroad, which was then in process of construction. He surveyed and recommended the route of the planned railroad between Cincinnati and Springfield, Ohio. He was adjutant-general of the state of Ohio from 1841 to 1848.

Mitchel played the leading role in establishing an observatory in Cincinnati. He convinced Nicholas Longworth to donate land for the project: the site of the future observatory was a 4-acre lot at the top of Mt. Ida, some 400 feet above the city of Cincinnati.

Mitchel generated public enthusiasm for astronomy through a series of public lectures. At that time, there were a few small telescopes in the country, but no organized observatory with a powerful instrument existed. Mitchel was able to interest a number of people in the possibility of erecting the first such observatory in the United States. At the end of one of his lectures, Mitchel presented his plan to an audience of 2,000. The plan was to organize the Cincinnati Astronomical Society, members of which would be shareholders in the observatory. Their shares would go for the purchase of a first-class instrument, and would entitle them to the use of the telescope. He promised to serve as director of the observatory for the first 10 years without pay.

In three weeks, 300 subscribers had been obtained, and Mitchel set out to purchase the telescope. On June 16, 1842, he booked passage on a sailing vessel to Europe, not having enough money to go in a steamer. He traveled to Fraunhofer's optical institute in Munich, where he procured a 12-inch objective lens for his telescope. In England he entered the Greenwich Observatory as a student for a few months.

Returning to the United States, Mitchel undertook the supervision of the construction of the observatory. On the 9th of November, 1843, the cornerstone was laid by John Quincy Adams, former President of the United States. Adams had a deep interest in astronomical science, and had tried unsuccessfully in 1825 to persuade Congress to found a National Observatory. Although 77 years old, and not in the best of health, Adams travelled to Cincinnati for the occasion because he felt that the founding of the Cincinnati Observatory was an important step to be taken if the United States were to become internationally recognized for its intellectual and scientific endeavors. At the dedication, Adams gave his last public speech. Mt. Ida was renamed Mt. Adams following this event.

When the observatory building foundation had been laid, the country was still in an economic depression, and with nearly all of the money raised having gone to the purchase of the telescope (which cost about $10,000, a considerable sum in those days), the project was without any money for its completion. Mitchel raised some additional money (and paid for much of it out of his own funds), while the majority of workmen gave their time and labor in exchange for shares in the Society.

The telescope arrived in January 1845. In March 1845 Mitchel began hoisting the telescope into place; it went into operation on April 14, 1845. At the time, it was the second-largest refracting telescope in the world. By June 1845 the building was complete and its telescope in place. Under Mitchel's leadership, the observatory was utilized for astronomical research, as well as general viewing and educational purposes.

Because there were no funds for an endowment for the new Cincinnati Observatory, Mitchel had agreed to serve as director without salary, relying on his income from the Cincinnati College. However, the college burned down, and he was left without a job or any monetary support. Mitchel still continued serve as director of the Observatory, as he had promised. He supported himself by civil engineering on the Ohio & Mississippi Railroad and by lecturing. He began serious scientific investigations with the telescope. It was at this time that he discovered the stellar companion to the bright star Antares.

It was also during this period that he founded The Sidereal Messenger, the first astronomical publication in the United States. In 1848 he also developed what was probably the first working chronograph for automatically recording the beats of a clock, a necessity for accurate timing observations. This was part of a larger program to automatically transmit time and observational information in "real time" over telegraph wires. It was developed, in part, because of an experiment using telegraphy of time signals to determine the longitude of Cincinnati with respect to Philadelphia. It had been suggested by Sir George Airy, the Astronomer Royal in England, that Cincinnati be the zero-point for land surveys in the United States, as Greenwich was in England.

|

| Nicholas Longworth |

In three weeks, 300 subscribers had been obtained, and Mitchel set out to purchase the telescope. On June 16, 1842, he booked passage on a sailing vessel to Europe, not having enough money to go in a steamer. He traveled to Fraunhofer's optical institute in Munich, where he procured a 12-inch objective lens for his telescope. In England he entered the Greenwich Observatory as a student for a few months.

Returning to the United States, Mitchel undertook the supervision of the construction of the observatory. On the 9th of November, 1843, the cornerstone was laid by John Quincy Adams, former President of the United States. Adams had a deep interest in astronomical science, and had tried unsuccessfully in 1825 to persuade Congress to found a National Observatory. Although 77 years old, and not in the best of health, Adams travelled to Cincinnati for the occasion because he felt that the founding of the Cincinnati Observatory was an important step to be taken if the United States were to become internationally recognized for its intellectual and scientific endeavors. At the dedication, Adams gave his last public speech. Mt. Ida was renamed Mt. Adams following this event.

|

| John Quincy Adams |

The telescope arrived in January 1845. In March 1845 Mitchel began hoisting the telescope into place; it went into operation on April 14, 1845. At the time, it was the second-largest refracting telescope in the world. By June 1845 the building was complete and its telescope in place. Under Mitchel's leadership, the observatory was utilized for astronomical research, as well as general viewing and educational purposes.

|

| The Mt. Adams Observatory |

It was also during this period that he founded The Sidereal Messenger, the first astronomical publication in the United States. In 1848 he also developed what was probably the first working chronograph for automatically recording the beats of a clock, a necessity for accurate timing observations. This was part of a larger program to automatically transmit time and observational information in "real time" over telegraph wires. It was developed, in part, because of an experiment using telegraphy of time signals to determine the longitude of Cincinnati with respect to Philadelphia. It had been suggested by Sir George Airy, the Astronomer Royal in England, that Cincinnati be the zero-point for land surveys in the United States, as Greenwich was in England.

Eventually, Mitchel had to temporarily leave Cincinnati to find some source of income. Because his lectures in Cincinnati had been so well received, he spent much of his time from 1842 to 1848 lecturing around the country on astronomy to large public audiences. Mitchel's enthusiasm and clarity impressed the people who heard his talks. The great expansion of interest in astronomy, and the proliferation of observatories during the next few years owes a great deal to the efforts of Mitchel, who has sometimes been called "The Father of American Astronomy."

Mitchel was chief engineer of the Ohio & Mississippi railroad in 1848-49 and again in 1852-53. He also helped establish observatories for the United States Navy and at Harvard University.

Mitchel was the author of several works on astronomy, the principal of which are The Planetary and Stellar Worlds (1848) and The Orbs of Heaven (1851). In his Astronomy of the Bible, the theology which he learned from the stars was Calvinistic. In his final lecture, after showing that the universe was governed by immutable law, he concluded with this passage:

When the American Civil War began in 1861, Mitchel made a speech in Union Square, New York City:

Mitchel's wife of 30 years, Louisa, died on August 21, 1861.

At the request of the citizens of Cincinnati, Mitchel was transferred to that city and commanded the Department of the Ohio from Sept. 19 to Nov. 13 1861. He organized the northern Kentucky defenses around Cincinnati. Mitchel led a division in the Army of the Ohio from December 1861 to July 1862. William Haines Lytle of Cincinnati commanded the Fourth Ohio Regiment in General Mitchel's brigade.

Mitchel assisted in the capture of Nashville, Tennessee, by the Union Army on February 23, 1862. The mayor of Nashville surrendered the city to Mitchel. The Nashville correspondent of The Cincinnati Gazette reported in March:

The raid began on April 12, 1862 when the regular morning northbound passenger train with the locomotive General stopped at Big Shanty, Georgia on its regular run from Atlanta to Chattanooga, so that the crew and passengers could breakfast at the Lacy Hotel. There Andrews and his raiders hijacked the General and the train's first of several cars. Their plan was to operate the train north towards Chattanooga, stopping to damage or destroy the track, bridges, telegraph wires, and track switches behind them. They chose to capture the train at Big Shanty station because it had no telegraph office.

The train's conductor, William Allen Fuller, along with two other men, chased the stolen train, first on foot, then by handcar. Locomotives of the time normally averaged 15 miles per hour (24 km/h), with short bursts of an average speed of 20 miles per hour. In addition, the terrain north of Atlanta is very hilly; even today, average speeds are usually never greater than 40 miles per hour between Chattanooga and Atlanta. Since Andrews intended to stop periodically to perform acts of sabotage, a determined pursuer, even on foot, could conceivably have caught up with the train before it reached Chattanooga. Fuller spotted the locomotive Yonah at Etowah and commandeered it. Two miles south of Adairsville, however, the raiders had destroyed the tracks, and Fuller was forced to continue the pursuit on foot. Beyond the damage, he took command of the southbound locomotive Texas at Adairsville, running it backwards and tender-first northward.

The raiders never got far ahead of Fuller. First, destroying the railway behind the hijacked train was a slow process. he railway was too well built for their efforts to yield anything more than minor, temporary, and superficial damage. Second, the raiders had stolen a regularly scheduled train on its route, and they needed to keep to that train's timetable. If they reached a siding ahead of schedule, they would have had to wait there until scheduled southbound trains passed them before they could continue north. Third (and neither Andrews nor Mitchel understood or foresaw this,) Mitchel's threat to Chattanooga occurred long enough in advance of the commencement of Andrews’ raid that Confederate Military Railway officials in Chattanooga had sufficient time to order, organize, and implement the emergency evacuation of all engines and rolling stock in Chattanooga. Special freight trains with superior right of passage (over the single track line between Chattanooga and Atlanta) were made up in Chattanooga and ordered southbound, hauling critical railroad supplies away from the Union threat, so as to prevent their either being captured by General Mitchel or trapped uselessly inside Chattanooga during a Union siege of the city.

Andrews’ explanation to the station masters he encountered moving northward was that his train was a special northbound ammunition movement, ordered by General Beauregard. This story was sufficient for the isolated station masters Andrews encountered as he moved northwards (as he had cut the telegraph wires to the south), but it had no impact upon the train dispatchers and station masters north of him, whose telegraph lines to Chattanooga were working. The authorities in Chattanooga had given the conductors of southbound trains superior right of passage over all other train movements between Chattanooga and Atlanta, including the regularly scheduled passenger train that Andrews had stolen and was operating northbound. It was this mechanism of delay that gave Fuller all the time needed to close the distance between them.The raid on April 12 failed. Andrews and a number of his men were captured. Andrews himself was among eight men who were tried in Chattanooga. They were hanged in Atlanta by Confederate forces.

Writing about the exploit, Corporal William Pittenger said that the remaining raiders worried about also being executed. They attempted to escape and eight succeeded. Traveling for hundreds of miles in pairs, they all made it back safely to Union lines, including two who were aided by slaves and Union sympathizers and two who floated down the Chattahoochee River until they were rescued a Union ship.

The remaining six were held as prisoners of war and exchanged for Confederate prisoners on March 17, 1863.Secretary of War Edwin Stanton awarded some of the raiders with the first Medal of Honor. Private Jacob Wilson Parrott, who had been physically abused as a prisoner, was awarded the first medal.

Later all but two of the other soldiers also received the medals, with posthumous awards to families for those who had been executed. As a civilian, James Andrews was not eligible.

Although a military failure, the story of Andrew's Raid became known to American history as"The Great Locomotive Chase. The pursuit of Andrews' Raiders formed the basis of the Buster Keaton silent film, The General, and a 1956 Disney film, The Great Locomotive Chase.

When Buell headed west to support General Ulysses Grant at Shiloh, he left Mitchel to hold Nashville. While Andrew's raid was going on, Mitchel advanced on Huntsville, Alabama. He only had fifteen thousand troops under his command, and Confederate guerrillas successfully attacked his men. He sent the following report to Stanton in Washington, D.C.

During the rest of the month no services were held in the churches as all Huntsville citizens were restrained within the picket lines. Mary Jane Chadick, a resident of Huntsville, wrote in her diary:

On May 2nd twelve prominent men in Huntsville were arrested and "put into confinement under guard." One of these hostages was Bishop Lay who was locked up in the Probate Judge's office. Then followed two weeks of conferences, exchanged notes, consultations with each other, and interviews with General Mitchel. Mitchel wanted his prisoners to sign a statement which read in part, "We disapprove and abhor all unauthorized and illegal war; and we believe that citizens who fire upon railway trains, attack the guards of bridges, destroy the telegraph lines and fire from concealment upon pickets deserve and should receive the punishment of death." Bishop Lay wrote to his wife, "It is all an attempt to mortify and humiliate us. Let us possess our souls with patience." In another note, "Your chief anxiety must be that we may behave ourselves like men and Christians. There will be a trial of moral power. We must trust in God & keep good cheer." After an interview which the twelve had with Mitchel, Bishop Lay wrote, "He had no charges against us, he said, but arrested us to show that he would arrest anybody. He sent for us to make us use our influence to promote amicable relations between his army and our people. He proposed

conditions of release to us in writing. These were considered by the whole 12, and we declined subscription. We must take the consequences. I know not what they will be. I am very quiet & easy in mind. The way of duty is very plain— and to do nothing is easy."

Ivan Turchaninov was born into a Don Cossack family in the Russian Empire. In 1856, he and his wife immigrated to the United States, where he settled in Chicago and worked for the Illinois Central Railroad. John Basil Turchin, as he was now known, joined the Union army at the outbreak of the war in 1861 and became the colonel of the 19th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment. His unit was under the command of the newly organized Army of the Ohio under General Don Carlos Buell, who was impressed by Turchin. Buell promoted him to command a brigade in the Army of the Ohio's Third Division, commanded by General Mitchel.

The occupation of northern Alabama by this division of the Union Army led to attack by combined partisan and Confederate cavalry units. One attack overran one of Turchin's regiments at Athens, Alabama. Frustration had been building among these Union soldiers for weeks over the repeated attacks and Buell's conciliatory policy of protecting the rights and property of Southerners. The reported involvement of local citizens in the rout at Athens and the humiliation suffered by the Union soldiers led to the sacking of the town when Turchin brought up reinforcements. Turchin, after learning that the civilians of Huntsville had prevented several blacks from rescuing Union soldiers from being roasted alive between the engine and coal-car of a destroyed train, had become enraged. After reoccupying the town on May 2, 1862 Turchin assembled his men and reportedly told them: "I shut my eyes for two hours. I see nothing." He left the town to reconnoiter defensive positions, during which time his men ransacked the business district.

The list of charges from The Official Record of the War of the Rebellion includes details of his soldiers' actions:

General Mitchel hurried to the town immediately upon hearing of the incident, met with the victimized citizens, and encouraged them to establish a committee to gather complaints against individual soldiers. While Mitchel promised to punish those responsible, "if the perpetrators could be found," he was sympathetic to the frustration created in his men by rebel hit-and-run tactics.

At first, the "Sack of Athens" did not receive much attention from Union officers or northern newspapers. It was not until early July, when Buell arrived in Huntsville, that Turchin faced disciplinary action. Buell charged Turchin with several offenses, chiefly neglect of duty, conduct unbecoming an officer, and disobedience of orders. Buell insisted on court-martialing Turchin. Turchin's court proceedings received national attention and became a focal point for the debate on the conduct of the war, related to the conciliatory policy as Union casualties in the war mounted. The Cincinnati Times reported:

Garfield resigned from the panel before the trial ended due to health problems. The board found Turchin guilty of failing to control his men and violating Buell’s General Order No. 13a, which forbade depredations, and recommended he be discharged. They also recommended leniency, because of the circumstances of the action, which General Buell opposed.

However, for the previous several weeks, Turchin's wife and influential Illinois statesmen had been seeking redress in Washington, D.C. Their efforts were successful: Secretary of War Edwin Stanton recommended to Congress that Turchin be promoted to brigadier general. The promotion became official in mid-July and invalidated the court martial verdict because officers could only be tried by equals or superior officers. As a result of the promotion, Turchin outranked six of the court's seven members.

For a brief time in the summer of 1862, Turchin became a symbol of a fundamental change in public opinion among Northerners. The war goal of 1861 had been to restore the southern states to the Union, slavery and all. The rebellion was seen as the action of a hot-headed minority of southerners. It took a year of fighting to convince Northerners that the Confederacy had deep support and that defeating the South would entail a desperate struggle. Shiloh, fought in April 1862, drove home that point. A sizable minority turned against the war in disgust and formed the basis for a strong peace movement. To bolster support for the war, Republican newspapers, The Chicago Tribune among them, began to demonize the rebels with rumors of atrocities against northern soldiers. The brutal slave system had made southerners full of "the malignant fury and the foul lust of the savage," and therefore different from other Americans.

Norton then contacted The Louisville Courier with accusations that Mitchel was using his position to speculate in the illegal cotton trade, and that Mitchel had acquiesced in Turchin's pillage of Athens. The newspaper published the story, and it was picked up by other papers. Norton left his regiment without leave, and went to Washington to press charges against Mitchel. In July he presented a deposition to the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, hearing that Colonel Norton was in the capital without proper leave, and that his accusations violated normal military channels, issued an order for his arrest. Norton left the city, but was relieved of his command.

On the 24th of October, five weeks after his arrival, there was an outbreak of yellow fever at the Union camp. Mitchel and his two sons, who were on his staff, came down with the disease. Yellow fever presents in most cases with fever, nausea and pain. Though it generally subsides after several days, a toxic phase can follow that turns the skin of the afflicted yellow until death. This yellowing of the skin is behind the name of the disease.

Mitchel died in Beaufort, South Carolina of yellow fever on October 30, 1862. He was 52 years old.

His body was buried in the graveyard of the Episcopal Church at Beaufort. Later it was moved to the Mitchel family plot in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, where his wife was buried. His tombstone lists his date of birth as July 20, 1805. The inscription at the base reads:

The Huntsville Daily Confederate reported on November 12, 1862, the death of "his detestable lowness, Maj. Gen. O.M. Mitchel. No man ever had more winning ways to excite people's hatred than he. We have no space to do justice to his vices - virtues he showed none, in his dealings with the people of North Alabama."

MGS Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) observations of this region show the bright "Mountains of Mitchel" to be a somewhat elevated region of rough, heavily cratered southern highlands. However, the "Mountains of Mitchel" do not appear to be "mountains." There are other areas nearby at similar elevation that do not retain frost well into southern spring. Part of the Mountains of Mitchel feature includes a prominent, south-facing scarp (at center-left) that would tend to retain frost longer in the spring because it is somewhat protected from sunlight (which comes from the north). The persistence of frost on the Mountains of Mitchel remains mysterious, but new observations from the MGS MOC are helping to unravel the story. Thus far, it seems that the frost here, for whatever reason, tends to be brighter than frost in most other places within the polar cap.

After the Civil War broke out, the Cincinnati Observatory ceased operation, and remained dormant until 1868, with the appointment of Cleveland Abbe as its new director. Abbe strongly urged that the Observatory be moved, since the Mt. Adams site had been rendered unsuitable due to the heated air, smoke, and dust of the rapidly-growing city. At this time he also established a system of daily weather reports and storm predictions, earning him the nickname "Old Probabilities". His work impressed the federal government so much that he was summoned to Washington to establish the United States Weather Bureau, and the Observatory was once again shut down.

In 1871 the University of Cincinnati took over control of the Observatory, and began its move to a new location at Mt. Lookout, a few miles away. The move was complete in 1873, and the original cornerstone of the old observatory became part of the new building, built by Cincinnati architect Samuel Hannaford.

The original Mitchel telescope lens was refigured in 1876 and the original tube shortened. In 1904, the telescope was moved into a new building by Hannaford, called the Mitchel Building.

A larger instrument, a 16-inch refractor built by Alvan Clark & Sons, was installed in the main Observatory building.

The 1843 Merz und Mahler 11-inch refractor may be the oldest continually used telescope in the world. It is currently used for public education programs.

In 1979, the Observatory formally became part of the Physics Department of the University of Cincinnati. In 1997, Observatory received the Department of the Interior’s National Historic Landmark designation for the Cincinnati Observatory’s buildings and grounds. In 1999, the University of Cincinnati, which owns the Observatory, granted The Cincinnati Observatory Center a long-term lease to the Observatory buildings and grounds, and the Cincinnati Observatory Center became a private not-for-profit organization. With a commitment of support from the University of Cincinnati, the Center has implemented an expanded educational program. The educational program uses the buildings and equipment as a base for public science education programs and for supporting science education in local K-12 schools. In addition, volunteers donate hours of support.

Fort Mitchell, Kentucky was also named for him. The original town of Fort Mitchell was incorporated in March 1910. Through an oversight, the name of the town was spelled with two L’s. The exact location of Fort Mitchel is believed to have been on the hill between the end of Summit Lane and Barrington Road near the Dixie Highway. It was one of 23 Civil War forts and batteries manned by the Union armies and located on the hills and ridges of Northern Kentucky.

There are plans for a permanent, national "freedom park", at Mitchelville on Hilton Head Island, to include a heritage and educational center, archaeological digs, genealogy research, statues, and replicas of the "freedmen's" cottages, school and prayer house. Mitchelville Preservation Project, a non-profit organisation, wants Mitchel's actions honored, and recognition for the slaves who risked their lives fleeing to Hilton Head.

Two of the campaigners are Priscilla Mitchel and Johnnie Mitchell. Priscilla, 53, is a direct descendant of Ormsby Mitchel, and Johnnie, 65, is the direct descendant of slaves he freed. Their shared names are no coincidence. "Ex-slaves tended to take the names of good white people who had been nice to them," explains Johnnie, whose husband's slave ancestors were named after the general. "Meeting Priscilla was like meeting family, family that I didn't know but loved and cherished, we just bonded as sisters."

"I definitely credit everything, my life situation, my children's good fortune, my family, to General Mitchel - that's why I'm passionate about it, because one person can make a difference," says Johnnie.

The Toni Morrison Society, in partnership with the Mitchelville Preservation Project, dedicated a bench in honor of the historic settlement in Mitchelville Freedom Park, off Beach City Road on Hilton Head Island. The bench is the eighth the society has placed as part of its "Bench by the Road" series, which began with a dedication on Sullivan's Island near Charleston in 2008. Among the other locations are Oberlin, Ohio; Paris, France; and George Washington University in Washington, D.C. The project was inspired by an excerpt of an interview that Morrison, a Nobel laureate, conducted with World Magazine in 1989. In it, Morrison said: "There is no suitable memorial or plaque or wreath or wall or park or skyscraper lobby. There is no 300-foot tower. There's no small bench by the road," where people can reflect upon slavery and what sprang from it.

Mitchel was the author of several works on astronomy, the principal of which are The Planetary and Stellar Worlds (1848) and The Orbs of Heaven (1851). In his Astronomy of the Bible, the theology which he learned from the stars was Calvinistic. In his final lecture, after showing that the universe was governed by immutable law, he concluded with this passage:

No, my friends, the analogies of nature applied to the moral government of God would crush out all hope in the sinful soul. There for millions of ages these stern laws have reigned supreme. There is no deviation, no modification, no yielding to the refractory or disobedient. All is harmony because all is obedient. Close forever if you will this strange book claiming to be God’s revelation, blot out forever if you will its lessons of God’s creative power, God’s super-abounding providence, God’s fatherhood and loving guardianship to man, his erring off-spring, and then unseal the lids of that mighty volume which the finger of God has written in the stars of heaven, and in these flashing letters of living light we read only the dread sentence, ‘The soul that sinneth it shall surely die.’In another place, in speaking of the power of the astronomer, he said,

“By the power of an analysis created by his own mind the astronomer rolls back the tide of time and reveals the secrets hidden by countless years, or, still more wonderful, he predicts with prophetic accuracy the future history of the rolling spheres. Space withers at his touch, Time past, present and future become one mighty NOW.”In 1852, Mitchel provided the plans for another observatory, the Dudley Observatory in Albany, New York. In 1859, he accepted the directorship of Dudley, which paid him a regular salary.

When the American Civil War began in 1861, Mitchel made a speech in Union Square, New York City:

I owe allegiance to no particular State, and never did, and, God helping me, I never will. I owe allegiance to the Government of the United States. A poor boy, working my way with my own hands, at the age of twelve turned out to take care of myself as best I could, and beginning by earning but four dollars per month. I worked my way onward until this glorious Government of the United States gave me a chance at the Military Academy at West Point. There I landed with my knapsack on my back, and, I tell you God's truth, just a quarter of a dollar in my pocket. There I swore allegiance to the Government of the United States. I did not abjure the love of my own State, nor of my adopted State, but high above that was proudly triumphant and predominant my love for our common country. . . . When the rebels come to their senses we will receive them with open arms; but until that time, while they are trailing our glorious banner in the dust, when they scorn it, condemn it, curse it, and trample it under foot, I must smite, and in God's name I will smite, and as long as I have strength I will do it I am ready, God help me, to do my duty. I am ready to fight in the ranks or out of the ranks. Having been educated in the Academy, having been in the army several years, having served as a commander of a volunteer company for ten years, and having served as an Adjutant-General, I feel I am ready for something. I only ask to be permitted to act; and in God's name, give me something to do!Mitchel gave several speeches in Cincinnati, encouraging men to enlist. On August 8, Mitchel received a commission as a brigadier-general of Ohio volunteers.

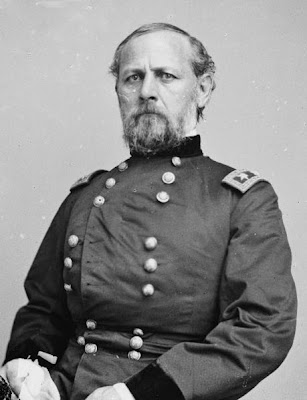

|

| Mitchel in Uniform as Union General |

At the request of the citizens of Cincinnati, Mitchel was transferred to that city and commanded the Department of the Ohio from Sept. 19 to Nov. 13 1861. He organized the northern Kentucky defenses around Cincinnati. Mitchel led a division in the Army of the Ohio from December 1861 to July 1862. William Haines Lytle of Cincinnati commanded the Fourth Ohio Regiment in General Mitchel's brigade.

|

| William Haines Lytle |

The following interesting scrap of news is told by an eye-witness to the scene: One day last week General Buell and the Brigadiers of the Department, who were present, went in a body to call upon Mrs. James K. Polk and her niece, daughter of Rev. Gen. Leonidas Polk. Mrs. Polk seemed determined that no doubt should be entertained as to her sentiments in regard to our unhappy difficulties. The gentlemen present, as they were severally addressed, simply bowed in silence, until Gen. Mitchel who was standing somewhat away from the party, was singled out. To him Mrs. P. remarked: "General, I trust this war will speedily terminate by the acknowledgment of Southern Independence." The remark was the signal for a lull in the conversation, and all eyes were turned upon the General to hear his reply. He stood with his lips firmly compressed, and his eyes looking fully into those of Mrs. Polk, as long as she spoke. He then said: "Madam, the man whose name you bear was once the President of the United States; he was an honest man and a true patriot, he administered the laws of this Government with equal justice to all. We know no independence of one section of our country which does not belong to all others, and judging by the past, of the mute lips of the honored dead, who lies so near us, could speak, they would express the hope that this war may never cease if that cessation was purchased by the dissolution of the Union of States over which he once presided." Needless to say that remark was, in a calm dignified tone, apt with that earnestness for which the General is noted, no offence could be taken. Southern independence was not mentioned again during the interview.Mitchel conspired with Union espionage agent James J. Andrews of Kentucky on plans to steal a Confederate train in Georgia and disrupt a railroad vital to the Confederate Army coincident with Mitchel's planned attack on Chattanooga. Mitchel planned to move south with his army and seize Huntsville, Alabama, before turning east in hopes of capturing Chattanooga. He believed that if he could block railroad reinforcement of the city from Atlanta to the south, he could take Chattanooga. And, once taken, the Union could enjoy the city's natural defenses. The Union Army would then have rail reinforcement and supply lines to its rear, leading west to the Union-held stronghold and supply depot of Nashville. Andrews, a civilian scout and spy, proposed to Mitchell a daring raid to destroy the Western and Atlantic Railroad as a useful supply link to Chattanooga, thereby isolating the city from Atlanta. He recruited the civilian William Hunter Campbell and 22 volunteer Union soldiers from three Ohio regiments. Andrews instructed the men to arrive in Marietta, George; they traveled in small parties in civilian attire to avoid arousing suspicion.

|

| James J. Andrews |

The train's conductor, William Allen Fuller, along with two other men, chased the stolen train, first on foot, then by handcar. Locomotives of the time normally averaged 15 miles per hour (24 km/h), with short bursts of an average speed of 20 miles per hour. In addition, the terrain north of Atlanta is very hilly; even today, average speeds are usually never greater than 40 miles per hour between Chattanooga and Atlanta. Since Andrews intended to stop periodically to perform acts of sabotage, a determined pursuer, even on foot, could conceivably have caught up with the train before it reached Chattanooga. Fuller spotted the locomotive Yonah at Etowah and commandeered it. Two miles south of Adairsville, however, the raiders had destroyed the tracks, and Fuller was forced to continue the pursuit on foot. Beyond the damage, he took command of the southbound locomotive Texas at Adairsville, running it backwards and tender-first northward.

|

| William Allen Fuller |

Andrews’ explanation to the station masters he encountered moving northward was that his train was a special northbound ammunition movement, ordered by General Beauregard. This story was sufficient for the isolated station masters Andrews encountered as he moved northwards (as he had cut the telegraph wires to the south), but it had no impact upon the train dispatchers and station masters north of him, whose telegraph lines to Chattanooga were working. The authorities in Chattanooga had given the conductors of southbound trains superior right of passage over all other train movements between Chattanooga and Atlanta, including the regularly scheduled passenger train that Andrews had stolen and was operating northbound. It was this mechanism of delay that gave Fuller all the time needed to close the distance between them.The raid on April 12 failed. Andrews and a number of his men were captured. Andrews himself was among eight men who were tried in Chattanooga. They were hanged in Atlanta by Confederate forces.

|

| Trial of James Andrews |

|

| William Pittenger |

The remaining six were held as prisoners of war and exchanged for Confederate prisoners on March 17, 1863.Secretary of War Edwin Stanton awarded some of the raiders with the first Medal of Honor. Private Jacob Wilson Parrott, who had been physically abused as a prisoner, was awarded the first medal.

|

| Jacob Wilson Parrott |

Later all but two of the other soldiers also received the medals, with posthumous awards to families for those who had been executed. As a civilian, James Andrews was not eligible.

|

| Monument to the Andrews Raiders, National Cemetery, Chattanooga, Tennessee |

|

| Buster Keaton in the film, The General |

HEADQUARTERS THIRD DIVISION, Huntsville, April 17, 1862.

Honorable E. M. STANTON, Secretary of War:

On Friday, the 11th, I entered Huntsville, capturing a large number of engines and cars. On Saturday expeditions were dispatched by rail east and west, seizing Stevenson and Decatur. Decatur was at once occupied. On Sunday we advanced cautiously upon Tuscumbia and Florence, and found the enemy had burned the railroad bridges. These were repaired and reconstructed. On Monday night I threw forward a strong force by rail to within 15 miles of Tuscumbia, and ordered them to advance prudently, in the hope of opening our communication directly with General Buell. From deserters we learn that the enemy had burned just in advance of us the bridge at Florence across the Tennessee and railway bridge between Tuscumbia and Corinth, thus manifesting their alarm at our approach. My point of operations extended from Stevenson to Tuscumbia. My entire effective force on that line scarcely exceeds 7,000 men. One of my regiments is at Fayetteville, another at Shelbyville, protecting my line of communication and supplies. Had I sufficient force I would deem it my duty to advance promptly upon Tuscumbia and throw myself in the rear of the enemy to Jacinto, on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. I send this directly to the Secretary of War, as I am uncertain whether any of my dispatches reached General Buell. None of them have been answered. I deem the line I occupy one of vast importance, and a heavier force is required for its defense and protection.

Very respectfully,

O. M. MITCHEL, Brigadier-General, Commanding Third Division.

|

| Union Soldiers in Huntsville, Alabama |

April 28, 1862: General Mitchel has been in a rage all the week on account of the cutting of the telegraph wires, the tearing up of the railroad track, firing into trains, and holds the citizens responsible for the same, having had 12 of the most prominent arrested. .. Great depredations have been committed by the Federal cavalry in the country surrounding Huntsville, and the citizens of Athens have suffered terribly.

|

| Mary Jane Chadick |

conditions of release to us in writing. These were considered by the whole 12, and we declined subscription. We must take the consequences. I know not what they will be. I am very quiet & easy in mind. The way of duty is very plain— and to do nothing is easy."

Ivan Turchaninov was born into a Don Cossack family in the Russian Empire. In 1856, he and his wife immigrated to the United States, where he settled in Chicago and worked for the Illinois Central Railroad. John Basil Turchin, as he was now known, joined the Union army at the outbreak of the war in 1861 and became the colonel of the 19th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment. His unit was under the command of the newly organized Army of the Ohio under General Don Carlos Buell, who was impressed by Turchin. Buell promoted him to command a brigade in the Army of the Ohio's Third Division, commanded by General Mitchel.

|

| John Basil Turchin |

The list of charges from The Official Record of the War of the Rebellion includes details of his soldiers' actions:

A party entered the dwelling of Milly Ann Clayton and opened all the trunks, drawers, and boxes of every description, and taking out the contents thereof, consisting of wearing apparel and bed-clothes, destroyed, spoiled, or carried away the same. They also insulted the said Milly Ann Clayton and threatened to shoot her, and then proceeding to the kitchen they there attempted an indecent outrage on the person of her servant girl.

A squad of soldiers went to the office of R.C. David and plundered it of about $1,000 in money and of much wearing apparel, and destroyed a stock of books, among which was a lot of fine Bibles and Testaments, which were torn, defaced, and kicked about the floor and trampled under foot.

For six or eight hours that day squads of soldiers visited the dwelling house of Thomas S. Malone, breaking open his desk and carrying off or destroying valuable papers, notes of hand, and other property, to the value of about $4,500, more or less, acting rudely and violently toward the females of the family. This last was done chiefly by the men of Edgarton’s battery. The plundering of saddles, bridles, blankets, etc., was by the Thirty-seventh Indiana Volunteers.

The store of Madison Thompson was broken open and plundered of a stock of goods worth about $3,000, and his stable was entered, and corn, oats, and fodder taken by different parties, who on his application for receipts replied “that they gave receipts at other places, but intended that this place should support them,” or words to that effect.

Squads of soldiers, with force of arms, entered the private residence of John F. Malone, and forced open all the locks of the doors, broke open all the drawers to the bureaus, the secretary, sideboard, wardrobes, and trunks in the house, and rifled them of their contents, consisting of valuable clothing, silver-ware, silver-plate, jewelry, a gold watch and chain, etc., and in the performing of these outrages they used coarse, vulgar, and profane language to the females of the family. These squads came in large numbers and plundered the house thoroughly. They also broke open the law office of said Malone and destroyed his safe and damaged his books. A part of this brigade went to the plantation of the above-named Malone and quartered in the negro huts for weeks, debauching the females and roaming with the males over the surrounding country to plunder and pillage.

A party of this command entered the house of R.S. Irwin and ordered his wife to cook dinner for them, and while she and her servant were so engaged they made the most indecent and beastly propositions to the latter in the presence of the whole family, and when the girl went away they followed her in the same manner, notwithstanding her efforts to avoid them.

Mrs. Hollinsworth’s house was entered and plundered of clothing and other property by several parties, and some of the men fired into the house and threatened to burn it, and used violent and insulting language toward the said Mrs. Hollinsworth. The alarm and excitement occasioned miscarriage and subsequently her death.

Several soldiers came to the house of Mrs. Charlotte Hine and committed rape on the person of a colored girl and then entered the house and plundered it of all the sugar, coffee, preservers, and the like which they could find. Before leaving they destroyed or carried off all the pictures and ornaments they could lay their hands on.

The house of J.H. Jones was entered by Colonel Mihalotzy, of the Twenty-fourth Illinois Volunteers, who behaved rudely and coarsely to the ladies of the family. He then quartered two companies of infantry in the house. About one hour after Captain Edgarton quartered his artillery company in the parlors, and these companies plundered the house of all provisions and clothing they could lay their hands on, and spoiled the furniture and carpets maliciously and without a shadow of reason, spoiling the parlor carpets by cutting bacon on them, and the piano by chopping joints on it with an axe, the beds by sleeping in them with their muddy boots on. The library of the house was destroyed, and the locks of the bureaus, secretaries, wardrobes, and trunks were all forced and their contents pillaged.

|

| Don Carlos Buell |

One of Gen. Mitchell's brigades is commanded by Col Turchin of Illinois. Turchin is an old European soldier, a Prussian by birth, an accomplished soldier but loose in his morals. His own regiment, the 19th Illinois, forms part of his brigade. "Since it has been in the service, the 19th Illinois has continually disgraced itself by committing depredations on citizens and especially upon Secessionists. At Bowling Green, their conduct was so outrageous, that Gen. Mitchell was compelled to interfere, and did so effectively. The regiment behaved themselves thereafter.

After Gen. Mitchell's arrival in Alabama, he dispatched Turchin, with his brigade, to Athens. The troops were constantly subjected to assassination by the citizens of that town. Almost every hour, soldiers were murdered in cold blood, by assassins who could not be discovered. Turchin became enraged, and one day let his men loose upon the town. As the story goes, he agreed to "shut his eyes" for two hours. The revenge of the men was fearful, no one being spared in the excesses which followed, and there is no doubt that crimes of a very grave character were perpetrated by the soldiery, especially by the 19th Illinois. At the end of the two hours, Turchin "opened his eyes" and the excesses ceased.

Brigadier General James A. Garfield oversaw the trial. At first, Garfield was appalled by Mitchel and Turchin's actions. Early in July, in a private letter to a friend, he wrote, "There has not been found in American history so black a page as that which will bear the record of Gen. Mitchel's campaign in North Alabama." As the trial progressed, however, Garfield changed his mind, saying Turchin had "quite won my heart." Garfield received a letter from his wife that reflected the public's view of the proceeding:

"I hope you will find Col. Turchin guilty of nothing unpardonable... severity and sternness should be turned to the punishment of rebels for the barbarities committed on our boys rather than to the punishment of our own... It seems very strange that as soon as a man begins to accomplish something in the way of putting down the rebellion he is recalled, or superseded, or disgraced in some way."

|

| James Garfield |

However, for the previous several weeks, Turchin's wife and influential Illinois statesmen had been seeking redress in Washington, D.C. Their efforts were successful: Secretary of War Edwin Stanton recommended to Congress that Turchin be promoted to brigadier general. The promotion became official in mid-July and invalidated the court martial verdict because officers could only be tried by equals or superior officers. As a result of the promotion, Turchin outranked six of the court's seven members.

Unfortunately for Buell and southerners, the methods Turchin used to hold secessionists accountable for their actions were gaining widespread acceptance in the army and in the North. By the summer of 1862, conciliation was no longer a viable military strategy. Prominent figures called for the removal of Buell and a more aggressive conduct of the war such that it be brought to a swift end.

A historical marker at the Limestone County Courthouse ensures the town never forgets the man who came to Athens and shut his eyes for two hours.

On a reconnaissance excursion, Mitchel discovered Colonel Jesse Smith Norton, commander of the 21st Ohio Infantry, attending a fishbake south of Huntsville with Alabama secessionists. As Norton was absent from his command without permission, and south of the Union picket lines, he was reprimanded by Mitchel, and ordered to return to his quarters under arrest. Norton was also charged with stealing and then selling government horses for personal profit.

|

| Jesse Smith Norton |

Mitchel left his command in Alabama at the beginning of July, and was promoted to major general. That month, Mitchel was seriously debating whether or not to resign his commission because of his differences of opinion with Buell. Rather than allow a competent officer to resign, the Secretary of War transferred Mitchel to Washington, D.C., and later reassigned him to South Carolina.

In September 1862, he assumed command of the X Corps and the Department of the South at Hilton Head, South Carolina. In 1861 the Union Army had liberated the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina and their main harbor Port Royal. The white residents fled, leaving behind 10,000 black slaves. Several private Northern charity organizations stepped in to help the former slaves become self-sufficient. The Port Royal Experiment was a program in which former slaves successfully worked on the land abandoned by plantation owners. The result was a model of what Reconstruction could have been.

Mitchel issued a military order freeing the slaves from Hilton Head and nearby islands, then set land aside to create a town, giving each a quarter-acre plot to grow crops and run their own affairs. They were able to buy land, vote, farm for wages, and grow sweet potatoes and greens which provided vital supplements to their diets. There were elected officials, taxes, street cleaners, stores selling household goods, and crucially, compulsory education for children aged six to 15, the first law of its kind in South Carolina. By 1862, the town had more than 1,500 residents.

|

| Union Dock at Hilton Head |

|

| "Refugee Quarters" Hilton Head |

“Good colored people, you have a great work to do, and you are in a position of responsibility. This experiment is to give you freedom, position, homes, your families, property, your own soil. It seems to me a better time is coming … a better day is dawning.”

~ Orsmby Mitchel

|

| U.S. General Hospital, Hilton Head, 1863 |

Mitchel died in Beaufort, South Carolina of yellow fever on October 30, 1862. He was 52 years old.

|

| Mitchel family plot in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York |

LOVE GOD SUPREMELY AND EACH OTHER MOST DEEPLY ARE YOUR FATHER'S DYING WORDS

|

| Mitchel's Grave in Green-Wood Cemetery, New York |

The first post-Civil War freedmen's town created in the United States, on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, was named "Mitchelville" for him. Mitchelville housed the first self-governing community of freed slaves during the Civil War - a unique and at the time revolutionary experiment predating Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation by several months.

In 1865, President Andrew Johnson ended the Port Royal Experiment, returning the land to its previous white owners.

A persistently bright region near the south pole of the planet Mars that was first observed by Mitchel in 1846 is named in his honor" "The Mountains of Mitchel". Mitchel deduced that this area might be mountainous because it seemed analogous to the snow that is left on Earth's mountain ranges in late spring and into summer. Snow can remain on high peaks because the air temperature decreases with elevation. In 1865, President Andrew Johnson ended the Port Royal Experiment, returning the land to its previous white owners.

MGS Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) observations of this region show the bright "Mountains of Mitchel" to be a somewhat elevated region of rough, heavily cratered southern highlands. However, the "Mountains of Mitchel" do not appear to be "mountains." There are other areas nearby at similar elevation that do not retain frost well into southern spring. Part of the Mountains of Mitchel feature includes a prominent, south-facing scarp (at center-left) that would tend to retain frost longer in the spring because it is somewhat protected from sunlight (which comes from the north). The persistence of frost on the Mountains of Mitchel remains mysterious, but new observations from the MGS MOC are helping to unravel the story. Thus far, it seems that the frost here, for whatever reason, tends to be brighter than frost in most other places within the polar cap.

After the Civil War broke out, the Cincinnati Observatory ceased operation, and remained dormant until 1868, with the appointment of Cleveland Abbe as its new director. Abbe strongly urged that the Observatory be moved, since the Mt. Adams site had been rendered unsuitable due to the heated air, smoke, and dust of the rapidly-growing city. At this time he also established a system of daily weather reports and storm predictions, earning him the nickname "Old Probabilities". His work impressed the federal government so much that he was summoned to Washington to establish the United States Weather Bureau, and the Observatory was once again shut down.

In 1871 the University of Cincinnati took over control of the Observatory, and began its move to a new location at Mt. Lookout, a few miles away. The move was complete in 1873, and the original cornerstone of the old observatory became part of the new building, built by Cincinnati architect Samuel Hannaford.

|

| The Observatory at Mt. Lookout |

|

| The Observatory and Mitchel Building |

|

| The Mitchel Building, Cincinnati Observatory |

|

| The 1843 Merz und Mahler 11-inch refractor in the Mitchel Building |

Fort Mitchell, Kentucky was also named for him. The original town of Fort Mitchell was incorporated in March 1910. Through an oversight, the name of the town was spelled with two L’s. The exact location of Fort Mitchel is believed to have been on the hill between the end of Summit Lane and Barrington Road near the Dixie Highway. It was one of 23 Civil War forts and batteries manned by the Union armies and located on the hills and ridges of Northern Kentucky.

There are plans for a permanent, national "freedom park", at Mitchelville on Hilton Head Island, to include a heritage and educational center, archaeological digs, genealogy research, statues, and replicas of the "freedmen's" cottages, school and prayer house. Mitchelville Preservation Project, a non-profit organisation, wants Mitchel's actions honored, and recognition for the slaves who risked their lives fleeing to Hilton Head.

Two of the campaigners are Priscilla Mitchel and Johnnie Mitchell. Priscilla, 53, is a direct descendant of Ormsby Mitchel, and Johnnie, 65, is the direct descendant of slaves he freed. Their shared names are no coincidence. "Ex-slaves tended to take the names of good white people who had been nice to them," explains Johnnie, whose husband's slave ancestors were named after the general. "Meeting Priscilla was like meeting family, family that I didn't know but loved and cherished, we just bonded as sisters."

|

| A BENCH BY THE ROAD Placed by The Mitchelville Preservation Project Hilton Head, South Carolina April 16, 2013 |