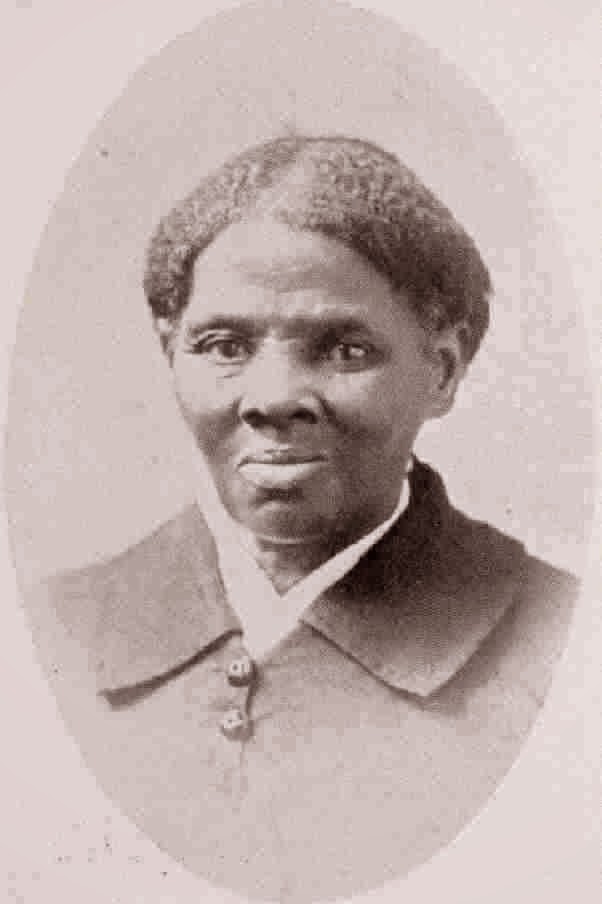

Araminta "Minty" Ross, who was later known as Harriet Tubman, was born to slave parents, Harriet ("Rit") Green and Ben Ross in Maryland, in the early 1820s. Neither the exact year nor place of her birth was recorded. The year 1822 is based on a midwife payment and several other historical documents, including a later runaway advertisement. She was probably born on Anthony Thompson’s plantation

|

| Dorechester County, Maryland (in green) |

In 1808, Harriet and Ben had their first child, Linah. According to court records, they had nine children together: Linah, born in 1808, Mariah Ritty in 1811, Soph in 1813, Robert in 1816, Minty (Harriet) in 1822, Ben in 1823, Rachel in 1825, Henry in 1830, and Moses in 1832.

Anthony Thompson had married Mary Pattison Brodess when Edward was a small child; when she died in 1810, Thompson became guardian of his nine-year-old stepson. Thompson remained in that role until Edward Brodess reached the age of twenty-one in 1822, when he became legally independent and gained rights to his inheritance, which included Rit and her children. He married Eliza Ann Keene in March 1824; they would have eight children over the next twenty years. By 1824, Rit Ross and her children were forced to move away from Ben Ross and the Thompson plantation, to Brodess’s farm in Bucktown, ten miles away. Edward Brodess and his stepfather were not on good terms when he came of age, and their difficulties made it impossible for the slaves they owned to continue living together.

|

| Slave sale in Easton, Maryland |

Edward Brodess, wanting more cash, sold one of Rit's daughters in 1825. Intending to make money from the other children as well, Brodess hired out Minty when she was five or six years old. In the 1869 biography of Tubman written by Sarah Bradford:

The first person by whom she was hired was a woman who was "Miss Susan" to her slaves. . . This woman was possessed of the good things of this life, and provided liberally for her slaves--so far as food and clothing went. But she had been brought up to believe, and to act upon the belief, that a slave could be taught to do nothing, and would do nothing but under the sting of the whip. Harriet, then a young girl, was taken from her life in the field, and having never seen the inside of a house better than a cabin in the negro quarters, was put to house-work without being told how to do anything. The first thing was to put a parlor in order. "Move these chairs and tables into the middle of the room, sweep the carpet clean, then dust everything, and put them back in their places!" These were the directions given, and Harriet was left alone to do her work.

The whip was in sight on the mantel-piece, as a reminder of what was to be expected if the work was not done well. Harriet fixed the furniture as she was told to do, and swept with all her strength, raising a tremendous dust. The moment she had finished sweeping, she took her dusting cloth, and wiped everything "so you could see your face in 'em, de shone so," in haste to go and set the table for breakfast, and do her other work. The dust which she had set flying only settled down again on chairs, tables, and the piano. "Miss Susan" came in and looked around. Then came the call for "Minty"-- Harriet's name was Araminta at the South. She drew her up to the table, saying, "What do you mean by doing my work this way, you--!" and passing her finger on the table and piano, she showed her the mark it made through the dust. "Miss Susan, I done sweep and dust jus' as you tole me." But the whip was already taken down, and the strokes were falling on head and face and neck. Four times this scene was repeated before breakfast, when, during the fifth whipping, the door opened, and "Miss Emily" came in. She was a married sister of "Miss Susan," and was making her a visit, and though brought up with the same associations as her sister, seems to have been a person of more gentle and reasonable nature. Not being able to endure the screams of the child any longer, she came in, took her sister by the arm, and said, "If you do not stop whipping that child, I will leave your house, and never come back!" Miss Susan declared that "she would not mind, and she slighted her work on purpose." Miss Emily said, "Leave her to me a few moments;" and Miss Susan left the room, indignant. As soon as they were alone, Miss Emily said: "Now, Minty, show me how you do your work." For the sixth time Harriet removed all the furniture into the middle of the room; then she swept; and the moment she had done sweeping, she took the dusting cloth to wipe off the furniture. "Now stop there," said Miss Emily; "go away now, and do some of your other work, and when it is time to dust, I will call you." When the time came she called her, and explained to her how the dust had now settled, and that if she wiped it off now, the furniture would remain bright and clean. These few words an hour or two before, would have saved Harriet her whippings for that day, as they probably did for many a day after.

As a child, Minty also worked at the home of a planter named James Cook. She had to check the muskrat traps in nearby marshes; after contracting measles, she became so ill that Cook sent her back to Brodess, where her mother nursed her back to health. Brodess then hired her out again. These separations from her family exacted a heavy toll on her, and she suffered loneliness and fear throughout her childhood.

Brodess hired out other members of Tubman’s family; his farm was too small to productively use all the enslaved labor he owned, and Brodess constantly needed cash for his living expenses. He sold three of Tubman’s sisters, Linah, Mariah Ritty, and Soph, to out-of-state buyers. Linah and Soph both left young children behind. Brodess turned the proceeds from their sales into land purchases to expand his own farm. When a trader from Georgia approached Brodess about buying Rit's youngest son, Moses, she hid him for a month, aided by other slaves and free blacks in the community. At one point she confronted her owner about the sale. Finally, Brodess and "the Georgia man" came toward the slave quarters to seize the child, where Rit told them, "You are after my son; but the first man that comes into my house, I will split his head open." Brodess backed away and abandoned the sale.

Brodess hired out other members of Tubman’s family; his farm was too small to productively use all the enslaved labor he owned, and Brodess constantly needed cash for his living expenses. He sold three of Tubman’s sisters, Linah, Mariah Ritty, and Soph, to out-of-state buyers. Linah and Soph both left young children behind. Brodess turned the proceeds from their sales into land purchases to expand his own farm. When a trader from Georgia approached Brodess about buying Rit's youngest son, Moses, she hid him for a month, aided by other slaves and free blacks in the community. At one point she confronted her owner about the sale. Finally, Brodess and "the Georgia man" came toward the slave quarters to seize the child, where Rit told them, "You are after my son; but the first man that comes into my house, I will split his head open." Brodess backed away and abandoned the sale.

In late fall, sometime between 1834 and 1836, Minty was nearly killed. She had been hired out to a neighboring farmer, and one evening she accompanied the family's cook to the local store to purchase items for the kitchen. When they arrived at the store, she encountered a slave owned by another family, who had left the fields without permission. His overseer, furious, demanded that Minty help restrain the young man. She refused, and as the slave ran away, the overseer threw a two-pound weight at him. He struck Minty instead, which she said "broke my skull." She later explained her belief that her hair – which "had never been combed and ... stood out like a bushel basket" – might have saved her life. The weight struck the girl's head with such force that it fractured her skull and drove fragments of her shawl into her head. Bleeding and unconscious, Tubman was returned to her owner's house, where she remained without medical care for two days.

They carried me to the house all bleeding and fainting. I had no bed, no place to lie down on at all, and they lay me on the seat of the loom, and I stayed there all that day and the next.She was sent back into the fields, "with blood and sweat rolling down my face until I couldn't see." She was sent back to Brodess, who attempted to sell her, but no buyer was interested in purchasing a sick and wounded slave. “They said they wouldn’t give a sixpence for me,” she later told Sarah Bradford. The injury left her suffering from headaches, seizures, and periods of semi-consciousness for the rest of her life.

In addition, she had dreams, visions and heard music:

We'd been carting manure all day, and t'other girl and I was gwine home on the sides of the cart . . . when suddently I heard such music as filled all the air.She often dreamed of flying over fields, rivers, mountains, and towns, looking down on them "like a bird."

As a child, she had been told Bible stories by her mother, and developed a passionate faith in God. She rejected the teachings of the New Testament that urged slaves to be obedient, and found guidance in the Old Testament tales of deliverance. She also had dream and visions which she considered to be revelations from the divine.

As she grew older and stronger, she was assigned to field and forest work, driving oxen, plowing, and hauling logs.

In 1836, Anthony Thompson died, leaving provisions in his will for Ben Ross to be manumitted five years after Thompson's death. Thompson also requested that Ben receive a piece of land on his property, becoming a perpetual free laborer.

In 1836, Anthony Thompson died, leaving provisions in his will for Ben Ross to be manumitted five years after Thompson's death. Thompson also requested that Ben receive a piece of land on his property, becoming a perpetual free laborer.

|

| Dorchester County |

Minty was hired out to John T. Stewart, a Dorchester County farmer, merchant, and shipbuilder. Laboring first in Stewart’s house, she soon began working in his fields, docks, and timber yards, exhibiting strength and endurance. Brodess eventually allowed her to hire herself out, after paying him a yearly fee of sixty dollars for the privilege to work for herself. This allowed her to earn enough money to buy a pair of oxen.

By 1840, her father was manumitted from slavery at the approximate age of 45. He continued working as a timber estimator and foreman for the Thompson family, who had held him as a slave.

Around 1844, Minty married a free black man named John Tubman. Little is known about him or their time together. Since the mother's status determined that of her children, any children born to the couple would be the property of Edward Brodess.

|

| 1844 Reward for runaway slave owned by Absalom Thompson brother of Anthony C. Thompson |

Around 1844, Minty married a free black man named John Tubman. Little is known about him or their time together. Since the mother's status determined that of her children, any children born to the couple would be the property of Edward Brodess.

In 1847, Minty hired herself out to Dr. Anthony C. Thompson, Anthony Thompson’s son. In 1849, she became ill again. Edward Brodess tried to sell her, but could not find a buyer. Angry at his action and the unjust hold he kept on her family members, Minty began to pray for her owner, asking God to make him change his ways:

She said, "from Christmas till March I worked as I could, and I prayed through all the long nights--I groaned and prayed for ole master: 'Oh Lord, convert master!' 'Oh Lord, change dat man's heart!' 'Pears like I prayed all de time," said Harriet; " 'bout my work, everywhere, I prayed an' I groaned to de Lord. When I went to de horse-trough to wash my face, I took up de water in my han' an' I said, 'Oh Lord, wash me, make me clean!' Den I take up something to wipe my face, an' I say, 'Oh Lord, wipe away all my sin!' When I took de broom and began to sweep, I groaned, 'Oh Lord, wha'soebber sin dere be in my heart, sweep it out, Lord, clar an' clean!'" . . .

"An' so," said she, "I prayed all night long for master, till the first of March; an' all the time he was bringing people to look at me, an' trying to sell me. Den we heard dat some of us was gwine to be sole to go wid de chain-gang down to de cotton an' rice fields, and dey said I was gwine, an' my brudders, an' sisters. Den I changed my prayer. Fust of March I began to pray, 'Oh Lord, if you ant nebber gwine to change dat man's heart, kill him, Lord, an' take him out ob de way.'On March 7, 1849, Edward Brodess, died on his farm at Bucktown at the age of forty-seven. She expressed regret for her earlier sentiments:

"Nex' ting I heard old master was dead, an' he died jus' as he libed. Oh, then, it 'peared like I'd give all de world full ob gold, if I had it, to bring dat poor soul back. But I couldn't pray for him no longer."

The slaves were told that their master's will provided that none of them should be sold out of the State. This satisfied most of them, and they were very happy. But Harriet was not satisfied; she never closed her eyes that she did not imagine she saw the horsemen coming, and heard the screams of women and children, as they were being dragged away to a far worse slavery than that they were enduring there.At the time of Edward Brodess's death, he had eight children; five of them were under the age of eighteen. His estate was deeply in debt, leaving his widow Eliza Ann Brodess facing serious financial problems. In contrast to what the slaves were told, his death made it likely that property would be sold and the enslaved families broken apart, as frequently happened in estate settlements. According to his will, the slaves were held in trust for his young children. In April, Eliza Brodess received a court order to sell all of her husband's personal property, "negroes excepted," to pay his debts. She took out a loan for one thousand dollars and also petitioned the court to sell slaves in order to raise cash.

At some point in her young adult life, Minty began calling herself "Harriet" Tubman; she was approximately 40 years old when the Civil War began.

Harriet Tubman and her brothers ran away from their masters in September 1849. Tubman had been hired out to Dr. Anthony Thompson, who owned a large plantation in neighboring Caroline County; it is likely that her brothers labored for Thompson as well. At the beginning of October, Eliza Brodess posted a runaway notice in the Cambridge Democrat newspaper, offering a reward of up to 100 dollars for each slave returned.

The brother apparently had second thoughts about continuing their escape: Ben may have just become a father. The two men went back, and although Harriet may have returned with them, she soon ran away again, this time without her brothers. Her exact route is unknown. The Preston area in Caroline County had a Quaker community which was probably Tubman's first stop. From there, she made her way north into Pennsylvania, a journey of nearly 90 miles. She crossed into Pennsylvania with a feeling of relief and awe, and recalled the experience years later:

When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.

Philadelphia and the surrounding area contained the largest concentration of free blacks in

the nation. By 1850 there were more free blacks living in Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland than in all the other states combined. Philadelphia had the largest community of blacks, with a population of 20,000 by 1847. The Underground Railroad was active in the city, as were abolition societies.

One of the most prominent free black men in Philadelphia was Robert Purvis, a man of mixed race who chose to identify with the black community; he used his education and wealth to support the abolition of slavery, as well as projects in education to help the advance of African Americans. In 1833, Purvis had helped abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison establish the American Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. From 1845 to 1850, Purvis served as president of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, a biracial organization.Purvis also served as chairman of the General Vigilance Committee from 1852-1857, which gave direct aid to fugitive slaves. He used his own house, located outside the city, as a station on the Underground Railroad. Purvis supported many progressive causes in addition to abolition; with his good friend Lucretia Coffin Mott, he promoted the recognition of women's rights and suffrage. He believed in integrated groups working for greater progress for all. Lucretia Mott, a Quaker abolitionist, became one of Tubman's earliest supporters.

Harriet Tubman escaped to freedom as the conflict over slavery was increasing between the North and South. In January 1850, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky proposed a series of resolutions which he believed would reconcile Northern and Southern interests. Clay originally intended the resolutions to be voted on separately, but at the urging of southerners he agreed to the creation of a committee to consider the measures. As chairman of the committee, Clay presented an omnibus bill linking all of the resolutions. The resolutions included:

|

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

I had crossed the line. I was free; but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land; and my home, after all, was down in Maryland; because my father, my mother, my brothers, and sisters, and friends were there.

But I was free, and they should be free. I would make a home in the North and bring them there, God helping me. Oh, how I prayed then. . . I said to de Lord, 'I'm gwine to hole stiddy on to you, an' I know you'll see me through.'

|

| Executive Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, ca. 1851 Lucretia and James Mott are sitting on the right Robert Purvis is sitting next to them |

Harriet Tubman escaped to freedom as the conflict over slavery was increasing between the North and South. In January 1850, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky proposed a series of resolutions which he believed would reconcile Northern and Southern interests. Clay originally intended the resolutions to be voted on separately, but at the urging of southerners he agreed to the creation of a committee to consider the measures. As chairman of the committee, Clay presented an omnibus bill linking all of the resolutions. The resolutions included:

- Admission of California as a free state, ending the balance of free and slave states in the senate

- Organization of the Utah and New Mexico territories without any slavery provisions, giving the right to determine whether to allow slavery to the territorial populations

- Prohibition of the slave trade, but not the ownership of slaves, in the District of Columbia

- A more stringent Fugitive Slave Act

- Establishment of boundaries for the state of Texas in exchange for federal payment of Texas's ten million dollar debt.

- A declaration by Congress that it did not have the authority to interfere with the interstate slave trade.

The omnibus bill, despite Clay's efforts, failed in a crucial vote on July 31 with the majority of his Whig Party opposed. He announced on the Senate floor the next day that he intended to persevere and pass each individual part of the bill.

In August, as Congress was debating the new and harsher fugitive slave law, abolitionists gathered in the upstate New York town of Cazenovia to take protest against the bill. Over 2,000 people attended the Fugitive Slave Law Convention, including about 50 fugitive slaves.

|

| Fugitive Slave Law Convention, August 1850 |

Ezra Greenleaf Weld, brother of one of the abolitionists, Theodore Weld, was in the crowd; he was a Daguerrean artist and captured an image of some of the participants, including his brother Theodore, Gerrit Smith, Frederick Douglass, Abby Kelley Foster, and the Edmondson sisters.

On September 18, 1850, the U.S. Congress passed the Compromise of 1850. Among the provisions of the Compromise of 1850 was the creation of a stricter Fugitive Slave Law. Helping runaways had been illegal since 1793, but the 1850 law required that everyone, law enforcers and ordinary citizens, help catch fugitives.

In spite of pro-slavery advocates' claim to support "States' Rights" and the freedom of American citizens, their actions forced Northern states and their residents to not only support slavery, but to actively participate in it. Those who refused to assist slave-catchers, or aided fugitives, could be fined up to $1,000 (about $28,000 in present-day value) and jailed for six months. It also eliminated what little legal protection fugitives once had. Before 1850, some northern states had required slave-catchers to appear before an elected judge and be tried by a jury which would determine the validity of a claim. After the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, any black person could be taken from the street, accused of being a fugitive from slavery, and taken before a federally appointed commissioner who received $5 for every fugitive released - and $10 for every one sent south.

On September 18, 1850, the U.S. Congress passed the Compromise of 1850. Among the provisions of the Compromise of 1850 was the creation of a stricter Fugitive Slave Law. Helping runaways had been illegal since 1793, but the 1850 law required that everyone, law enforcers and ordinary citizens, help catch fugitives.

In spite of pro-slavery advocates' claim to support "States' Rights" and the freedom of American citizens, their actions forced Northern states and their residents to not only support slavery, but to actively participate in it. Those who refused to assist slave-catchers, or aided fugitives, could be fined up to $1,000 (about $28,000 in present-day value) and jailed for six months. It also eliminated what little legal protection fugitives once had. Before 1850, some northern states had required slave-catchers to appear before an elected judge and be tried by a jury which would determine the validity of a claim. After the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, any black person could be taken from the street, accused of being a fugitive from slavery, and taken before a federally appointed commissioner who received $5 for every fugitive released - and $10 for every one sent south.

The law also specified that any person, white or black, could be held responsible for the return of the alleged runaway to the alleged owner. It raised all fines and terms of imprisonment for violation of the law. It made any federal marshal or other official who did not arrest an alleged runaway slave liable to a fine of $1,000. Law-enforcement officials everywhere were now obliged to arrest anyone suspected of being a runaway slave on no more evidence than a claimant's testimony of ownership. The law not only threatened the freedom of all people of color, it also destroyed the freedom of all people, black or white, in the free states by demanding their participation in the capture and return of enslaved people.

There were, however, no penalties in the law for those who made false claims or abducted free people, whether black or white. Free blacks and anti-slavery groups argued the system actually bribed commissioners to send kidnapped people into slavery, and obliged citizens to participate in the slavery system. The Fugitive Slave Law brought the issue home to citizens in the North, as it made them and their institutions responsible for enforcing slavery.

Abolitionists were now faced with the immediate choice of defying what they believed to be an unjust law or breaking with their own consciences and beliefs. It brought a defiant response from many people, both white and black. Reverend Luther Lee, pastor of the Wesleyan Methodist Church of Syracuse, New York, wrote:

Abolitionists were now faced with the immediate choice of defying what they believed to be an unjust law or breaking with their own consciences and beliefs. It brought a defiant response from many people, both white and black. Reverend Luther Lee, pastor of the Wesleyan Methodist Church of Syracuse, New York, wrote:

I never would obey it. I had assisted thirty slaves to escape to Canada during the last month. If the authorities wanted anything of me, my residence was at 39 Onondaga Street. I would admit that and they could take me and lock me up in the Penitentiary on the hill; but if they did such a foolish thing as that I had friends enough on Onodaga County to level it to the ground before the next morning.

|

| Lucretia Mott |

Twelfth month 22d, 1850. Lucretia Mott came forth with a fresh testimony against slavery and the Fugitive Slave Law. She cited a case where a colored man from Jersey, coming from market yesterday, was arrested, bound and hurried away South, after undergoing a partial examination, which she considered illegal.

Even colored people who had been free all their lives felt themselves very insecure in their freedom, for under this law the oaths of any two villains were sufficient to consign a free man to slavery for life.

While the law was a terror to the free, it was a still greater terror to the escaped bondman. To him there was no peace. Asleep or awake, at work or at rest, in church or market, he was liable to surprise and capture. By the law the judge got ten dollars a head for all he could consign to slavery, and only five dollars apiece for any which he might adjudge free.

Although I was now myself free, I was not without apprehension. My purchase was of doubtful validity, having been bought when out of the possession of my owner and when he must take what was given or take nothing. It was a question whether my claimant could be estopped by such a sale from asserting certain or supposable equitable rights in my body and soul.

|

| 1849 advertisement for the sale of Tubmman's niece, Kizziah |

Tubman began working with Thomas Garrett, a Quaker in Wilmington, Delaware. Garrett was an abolitionist and leader in the Underground Railroad movement. Garrett had been born into a prosperous Quaker family in Pennsylvania. When he was a young man, a family servant was kidnapped by men who planned to sell her as a slave in the South. Garret tracked them down and rescued her. Garret moved to Wilmington, Delaware and established a prosperous iron and hardware business. In 1827, he was an officer of the Delaware Abolition Society and represented the group at the National Convention of Abolitionists. Garrett openly worked as a stationmaster for the Underground Railroad; Thomas Garrett would secure transportation to William Still's office in Philadelphia, or the homes of other Underground Railroad operators in the greater Philadelphia area.

In 1848, Garrett and his friend John Hunn were brought to trial under the Fugitive Slave Act

|

| Thomas Garrett |

Thou has left me without a dollar, and I say to thee and to all in this court room, that if anyone knows a fugitive who wants shelter, send him to Thomas Garrett and he will befriend him...

A lien was put on Garrett's house and business until the fine was paid. With the aid of friends, Garrett paid the fine and continued in his iron and hardware business and helping runaway slaves to freedom. Harriet Beecher Stowe cited Garrett's 1848 trial as inspiration for some scenes in her anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin In her book, Garrett was the model for Simeon Halliday, the benevolent Quaker.

Tubman passed through Garrett's station many times, and he frequently provided her with money to continue her missions of guiding runaway slaves to freedom. Garrett later wrote of Tubman that he

never met with any person, of any color, who had more confidence in the voice of God, as spoken direct to her soul . . . and her faith in a Supreme Power truly was great.In the fall of 1851, Tubman returned to Dorchester County for the first time since her escape in 1849. She had worked and saved money, rented a place to live, and she intended to bring her husband, John, back to Philadelphia with her. However, in the intervening two years, John Tubman had married a free black woman named Caroline. Franklin Sanborn, in his biographical sketch of Tubman in 1863, wrote that:

She bought a nice suit of men's clothes, and went back to Maryland for her husband. But the faithless man had taken to himself another wife. Harriet did not dare venture into her presence, but sent word to her husband where she was. He declined joining her. At first her grief and anger were excessive . . . but finally she thought . . . "if he could do without her, she could without him," and so "he dropped out of her heart," and she determined to give her life to brave deeds.Suppressing her anger, she found some slaves who wanted to escape and led them to Philadelphia. John and Caroline Tubman raised a family of four children together as free blacks in Maryland.

A few months later, in December 1851, Tubman guided an unidentified group of 11 fugitives, possibly including the Bowleys, northward. There is evidence to suggest that Tubman and her group stopped at the home of Frederick Douglass. In his third autobiography, Douglass wrote:

On one occasion I had eleven fugitives at the same time under my roof, and it was necessary for them to remain with me until I could collect sufficient money to get them on to Canada. It was the largest number I ever had at any one time, and I had some difficulty in providing so many with food and shelter.

On Christmas day, 1854, Tubman and six runaways, including her three brothers, arrived at Ben Ross' cabin in Caroline County. The holidays were an ideal time to escape, as masters often allowed their slaves to visit nearby family and enjoy a few days outside of direct supervision. The group hid in the corn crib in Ben's barn. Tubman did not want her mother to know that she was helping her brothers escape because she believed Rit would not be able to hide her emotions about their secret. Tubman sent the two of the runaways, John Chase and Peter Jackson, to alert her father to their presence. Ben Ross did not want to actually see his children, knowing that if the authorities questioned him on the whereabouts of his missing sons, Ross could honestly say that he had not "seen" them. Ben gave the group of runaways food and clothing while keeping his eyes closed.

The group left for Delaware, and after 3 days arrived at Thomas Garrett's home in Wilmington. Garret wrote a letter to their mutual friend, J. Miller McKim:

Wilmington, 12 mo. 29th, 1854

Esteemed Friend, J. Miller McKim:

We made arrangements last night, and sent away Harriet Tubman, with six men and one woman to Allen Agnew's, to be forwarded across the country to the city. Harriet, and one of the men had worn their shoes off their feet, and I gave them two dollars to help fit them out . . .When they reached William Still's office in Philadelphia, they told him their stories, which he later included in his 1872 book:

Harriet was a woman of no pretensions . . . Yet in point of courage, shrewdness and disinterested exertions to rescue her fellow-men . . . she was without equal. Her success was wonderful. Time and again she made successful visits to Maryland . . . and would be absent for weeks at a time, running daily risks while making preparations for herself and passengers. Great fears were entertained for her safety, but she seemed wholly devoid of personal fear. . . She was much more watchful with those she was piloting . . . She would give all to understand that "times were very critical and therefore no foolishness would be indulged in on the road."

. . . December 29th, 1854 . . . Benjamin was twenty-eight years of age . . . Henry left his wife, Harriet Ann . . . Henry was only twenty-two . . . He was the father of two small children, whom he had to leave behind . . . Catherine {alias Jane}, aged twenty-two . . . affirmed that her master, "Rash Jones, was the worst man in the country." . . . Robert was thirty-five years of age . . . The civilization, religion, and customs under which Robert and his companions had been raised were, he thought, "very wicked." . . . They anticipated better days in Canada. . . . Clothing, food and money were given them to meet their wants, and they were sent on their way rejoicing.They took new names that they would use for the rest of their lives in the North. They all traveled safely to St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, where they remained during the rest of the 1850s. Benjamin Drew, a journalist from Boston, interviewed Tubman in St. Catharines in the summer of 1855. She was quoted as saying:

I have seen hundreds of escaped slaves, but I never saw one who was willing to go back and be a slave . . . I think slavery is the next thing to hell. If a person would send another into bondage, he would, it appears to me, he had enough to send him into hell, if he could.

In 1855 or 1856, Tubman brought Henry's free wife, Harriet Ann Parker, and their two children, William Henry, Jr. and John Isaac to Canada. William Henry Stewart settled in Grantham on the outskirts of St. Catharines, where he and Harriet Ann farmed, and raised a large family of 10 children.

Thomas Garrett wrote a letter to Eliza Wigham, Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society of Edinburgh on December 16, 1855:

Thomas Garrett wrote a letter to Eliza Wigham, Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society of Edinburgh on December 16, 1855:

. . . I feel as if I could not close this already too long letter, without giving someaccount of the doings of a noble woman . . a black one . . . She is strong and muscular, now about 55 years of age; born a Slave, and raised what is termed a field hand. She escaped from Slavery some 8 years since . . . She has made 4 successful trips to the neighborhood she left; & brought away 17 of her brothers, sisters, & friends & has mostly made the journeys down on foot, alone, & with her companions mostly walked back, traveling the whole distance at night, and secreting themselves during the day. She has three times gone to Canada with those she brought, and spent every dollar she could earn, or get in the cause. . . . Last week, after a trip of two weeks, she brought up one man. She took tea with me, & has left again with the determination (during the Christmas holidays) to bring away her sister, now the last left in slavery, & her three children, a sister in law & her three children, (the husband of the latter has been a Year in Canada), & one male friend. She says if she gets them away safely, she will be content, & give up such hazardous journeys, but says she will either accomplish it or be arrested . . . Shoud she be arrested for assisting a slave . . . she would be sold a slave for life . . . I can assure you I am proud of her acquaintance.

Eliza Wigham

In the decade before the Civil War began, Tubman returned repeatedly to the Eastern Shore of Maryland, rescuing some 70 slaves; she also provided instructions for about 50 to 60 other fugitives who escaped to the north. Her work required ingenuity and risk. She usually worked during winter months to minimize the likelihood that the group would be seen. According to Ednah Cheney:

Tubman used songs to relay messages. Sometimes she had to leave a group she was leading north, and told them to hide and wait for her signal. If she came back and sang one song two times, they would know it was safe to come out of hiding. But if there was danger, she would sing another song. This would mean that the group had to stay in hiding until Tubman sang the “all clear” song.

Samuel Green was a free black farmer and African American Episcopal minister in Dorchester County; he had been born in slavery but purchased his freedom as a young man. He was able to buy the freedom of his enslaved wife, Kitty, in 1842, but their two young children, Sam, Jr. and Susan, were sold by their owner to Dr. James Muse in 1847, taking them out of the Green household. In 1852, Green served as a delegate to the Convention of the Free Colored People of Maryland in Baltimore, where he resisted efforts to encourage emigration to Africa, and later attended the National Convention of the Colored People of the United States, held at Franklin Hall in Philadelphia, as a delegate from Maryland.

She always came in the winter, when the nights are long and dark, and people who have homes stay in them. She was never seen on the plantation herself; but appointed a rendezvous for her company eight or ten miles distant . . . She started on Saturday night . . . they would not be missed until Monday morning.Franklin Sanborn later wrote in his Commonwealth article:

|

| Franklin Sanborn |

When going on these journeys she often lay alone in the forests all night. Her whole soul was filled with awe of the mysterious Unseen Presence, which thrilled her with such depths of emotion, that all other care and fear vanished. Then she seemed to speak with her Maker "as a man talketh with his friend;" her child- like petitions had direct answers, and beautiful visions lifted her up above all doubt and anxiety into serene trust and faith. No man can be a hero without this faith in some form; the sense that he walks not in his own strength, but leaning on an almighty arm. Call it fate, destiny, what you will, Moses of old, Moses of to-day, believed it to be Almighty God.

Tubman was familiar with the abolitionist and Underground Railroad networks in Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts and Maryland. Although many of these helpers were secret, and remain so, according to Sara Bradford, Tubman was assisted by both Samuel Green of Maryland and Thomas Garrett of Delaware:

Sam Green, the man who was afterwards sent to State Prison for ten years for having a copy of "Uncle Tom's Cabin" in his house . . .

Thomas Garrett is a Quaker, and a man of a wonderfully large and generous heart, through whose hands, Harriet tells me, two thousand self-emancipated slaves passed on their way to freedom. He was always ready, heart and hand and means, in aiding these poor fugitives, and rendered most efficient help to Harriet on many of her journeys back and forth.

. . . When asked, as she often is, how it was possible that she was not afraid to go back, with that tremendous price upon her head, Harriet always answers, "Why, don't I tell you, Missus, t'wan't me, 'twas de Lord! I always tole him, 'I trust to you. I don't know where to go or what to do, but I expect you to lead me,' an' he always did."

|

| Samuel Green |

|

| Pages from William Still's August 1854 journal |

In August 1854, Sam Green’s son, Sam Jr., a skilled blacksmith, ran away from Dr. Muse after learning that he might be sold. Using instructions probably given to him by Tubman, he made his way to the office of William Still in Philadelphia. From there, he was sent along to Ontario, Canada, just across the U.S. border near Niagara Falls, where he joined other

|

| William Still |

|

| 1856 Reward advertisement from Cambridge, Maryland |

In March 1857, a group of slaves from Dorchester County called the "Dover Eight" fled to Delaware; a Dover man in the Underground Railroad network was to help them but instead turned them in for a $3,000 reward. In a dramatic escape, they kicked out a window of the Dover jail, jumped from the second story and hid in the woods until other abolitionists helped them. Seven were known to have reached freedom, but the fate of the unidentified one is unknown. Their flight and escape made national headlines.

The group had received help and shelter from Samuel Green in East New Market, then from Tubman's father, Ben Ross, at Poplar Neck in Caroline County. When the Dorchester County sheriff searched Green's house, he found the letters from Sam Jr. naming Jackson and Bailey. Raising further suspicions, Green had recently returned from a trip to Canada to visit with his son. Authorities also discovered a Canadian map, various railroad schedules, and a copy of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book, Uncle Tom's Cabin. Green was arrested on April 4, 1857, and charged with "knowingly having in his possession a certain abolition pamphlet called 'Uncle Tom's Cabin,' of an inflammatory character and calculated to create discontent amongst the colored population of this State" and "knowingly having in his possession certain abolition papers and pictorial representation of an inflammatory character calculated to create discontent amongst the colored population of this State." After a two week trial, Green was found guilty of a felony and sentenced to the ten years at the Maryland Penitentiary in Baltimore.

Word of Green's case spread throughout the country; support for Green began to build and letters arrived at Governor Thomas Watkins Ligon's door in favor of pardon. Letters from Dorchester County slave owners also arrived, demanding that Green should remain behind bars because of the many slave runaways in the area. The barrage of petitions continued when Thomas Holliday Hicks, a native of Dorchester County, became the governor. Hicks, a believer in the right to own slaves, declared that Green would remain in jail as long as he was governor, and kept his promise. The cost of the trial forced the Greens to sell their property in Dorchester County; Kitty then moved to Baltimore to be closer to her husband in prison, and supported herself by taking in laundry.

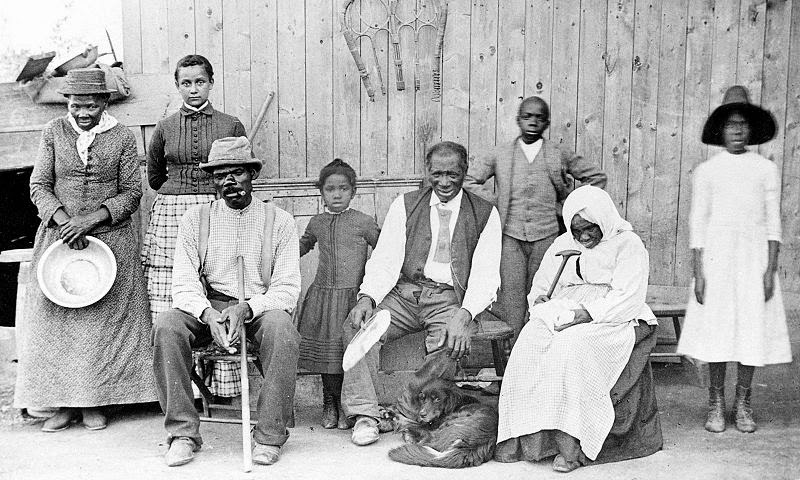

There was much suspicion of Ben Ross's participation in the Underground Railroad. Eastern Shore slave owners, particularly in Dorchester County, were desperate to stop the exodus of slaves. According to Thomas Garrett, Ben Ross was suspected of aiding the "Dover Eight." Believing that her parents' freedom, and possibily their lives, were in danger, Tubman made a trip down to Caroline County to escort her aging parents to safety. At almost seventy years of age, Ben and Harriet Ross fled Caroline County for Canada in June, 1857.

In early January 1858, Tubman spent a few days with Frederick Douglass and his family at their home in Rochester. Douglass wrote the Irish Ladies' Anti-Slavery Association that she had "been spending a short time with us since the holidays." Later that year, the fanatical abolitionist John Brown and twelve of his followers, including his son Owen, traveled to Chatham, Ontario, where on May 8 he convened a Constitutional Convention, put together with the help of Martin Delany. One-third of Chatham's 6,000 residents were fugitive slaves. John Brown was introduced to Harriet Tubman: he was so impressed by her that he referred to her as “General Tubman.” She became a devoted supporter, helping Brown recruit people for his plan to liberate slaves. Tubman later said that John Brown was the greatest white man she had ever met.

Tubman frequently attended abolition and suffrage meetings throughout New York and in the Boston area, sometimes under the pseudonym “Harriet Garrison” to protect her from slave catchers. Needing additional money to support her family and her rescues, Tubman turned to the antislavery lecture platform as a means to raise money for both her family and her missions. In the fall of 1858, SanbornSanborn was one of six influential men who supplied Brown with support for the raid on Harper's Ferry; the group was later termed the "Secret Six." Sanborn would defend Brown to the end of his life, assist in the support of his widow and children, and make periodic pilgrimages to Brown's grave.

Tubman also met Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who not only supported abolition, but also temperance, labor rights, and rights of women. He supported disunion abolitionism, organizing the Worcester Disunion Convention in 1857. The convention asserted abolition as its primary goal, even if it led the country to war. Higginson, a supporter of John Brown, was another of the "Secret Six" group who helped Brown raise money and acquire supplies for his intended slave insurrection. Higginson wrote in a letter to his mother:

|

| John Brown |

Tubman frequently attended abolition and suffrage meetings throughout New York and in the Boston area, sometimes under the pseudonym “Harriet Garrison” to protect her from slave catchers. Needing additional money to support her family and her rescues, Tubman turned to the antislavery lecture platform as a means to raise money for both her family and her missions. In the fall of 1858, SanbornSanborn was one of six influential men who supplied Brown with support for the raid on Harper's Ferry; the group was later termed the "Secret Six." Sanborn would defend Brown to the end of his life, assist in the support of his widow and children, and make periodic pilgrimages to Brown's grave.

Tubman also met Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who not only supported abolition, but also temperance, labor rights, and rights of women. He supported disunion abolitionism, organizing the Worcester Disunion Convention in 1857. The convention asserted abolition as its primary goal, even if it led the country to war. Higginson, a supporter of John Brown, was another of the "Secret Six" group who helped Brown raise money and acquire supplies for his intended slave insurrection. Higginson wrote in a letter to his mother:

Worchester, June 17, 1859

Dearest Mother:

We have had the greatest heroine of the age here, Harriet Tubman, a black woman, and a fugitive slave, who has been back eight times secretly and brought out in all sixty slaves with her, including all her own family, besides aiding many more in other ways to escape. Her tales of adventure are beyond anything in fiction and her ingenuity and generalship are extraordinary. I have known her for some time and mentioned her in speeches once or twice---the slaves call her Moses. She has had a reward of twelve thousand dollars offered for her in Maryland and will probably be burned alive whenever she is caught, which she probably will be, first or last, as she is going again. She has been in the habit of working in hotels all summer and laying up money for this crusade in the winter. She is jet black and cannot read or write, only talk, besides acting.

. . . A more ordinary specimen of humanity could hardly be found among the most unfortunate-looking farm hands of the South. Yet in point of courage, shrewdness, and disinterested exertions to rescue her fellow-man, she is without equal.

|

| Tubman's home in Fleming, New York |

William Seward was an opponent of the Fugitive Slave Act, and he defended runaway slaves in court. Seward’s wife. Frances, was deeply committed to the abolitionist movement. Although supportive of her husband's political career, Frances Seward did not choose to move with him to Washington. Ongoing health problems and the care of her aging father kept her in Auburn. The Seward family's Auburn home was a safehouse to fugitive slaves. Seward’s frequent

travel and political work meant that it was Frances who played the more active role in Auburn abolitionist activities. Frances Seward referred to the area over the woodshed as her "dormitory."

|

| Frances Seward |

|

| Henry Highland Garnet |

While staying with the Rev. Henry Highland Garnet in New York, a vision came to her in the night of the emancipation of her people. Whether a dream, or one of those glimpses into the future, which sometimes seem to have been granted to her, no one can say, but the effect upon her was very remarkable.

She rose singing, "My people are free!" "My people are free!" She came down to breakfast singing the words in a sort of ecstasy. She could not eat. The dream or vision filled her whole soul, and physical needs were forgotten.

Mr. Garnet said to her: "Oh, Harriet! Harriet! You've come to torment us before the time; do cease this noise! My grandchildren may see the day of the emancipation of our people, but you and I will never see it."

"I tell you, sir, you'll see it, and you'll see it soon. My people are free! My people are free."

When, three years later, President Lincoln's proclamation of emancipation was given forth, and there was a great jubilee among the friends of the slaves, Harriet was continually asked, "Why do you not join with the rest in their rejoicing!" "Oh," she answered, "I had my jubilee three years ago. I rejoiced all I could den; I can't rejoice no more."

On her way to Boston in April 1860, Tubman helped rescue a fugitive slave, Charles Nalle, from the custody of United States Marshals in Troy, New York, charged with returning him to his Virginia master. She attended the New England Anti-Slavery Society Conference in Boston in May, and visited Ralph Waldo Emerson's house, met Louisa May Alcott's family, and had tea with Horace Mann's wife.

Throughout the 1850s, Tubman had tried, unsuccessfully, to return to Maryland and bring away her one remaining enslaved sister, Rachel, along with Rachel's children. On her last known rescue mission in December 1860, Tubman arrived in Dorchester County and learned that Rachel had died. Unable to retrieve Rachel’s children, Tubman instead brought away the Ennals family, including a small infant who had to be drugged to keep it quiet as they fled. They safely reached the home of David and Martha Wright in Auburn, New York, on December 28, 1860. In Martha Wright's letter to her sister Lucretia on December 30, 1860,she wrote:

Throughout the 1850s, Tubman had tried, unsuccessfully, to return to Maryland and bring away her one remaining enslaved sister, Rachel, along with Rachel's children. On her last known rescue mission in December 1860, Tubman arrived in Dorchester County and learned that Rachel had died. Unable to retrieve Rachel’s children, Tubman instead brought away the Ennals family, including a small infant who had to be drugged to keep it quiet as they fled. They safely reached the home of David and Martha Wright in Auburn, New York, on December 28, 1860. In Martha Wright's letter to her sister Lucretia on December 30, 1860,she wrote:

We have been expending our sympathies, as well as congratulations, on sevennewly arrived slaves that Harriet Tubman has just pioneered safely from the Southern Part of Maryland. One woman carried a baby all the way and brought two other children that Harriet and the men helped along. They brought a piece of old comfort and a blanket in a basket with a little kindling, a little bread for the baby with some laudanum to keep it from crying during the day.

Martha Coffin Wright

After acquiring the Auburn property, Tubman went back to Maryland at some point and returned with a light-skinned black girl named Margaret, who she said was her niece. The identity of Margaret's parents is unknown. Years later, Margaret's daughter, Alice Lucas Brickler, said that Tubman "had taken the child from a sheltered good home to a place where there was nobody to care for her." Alice Brickler described it as a "kidnapping." There has been speculation that Margaret was actually Tubman's daughter, or that she had another reason for taking the child, and kept the actual circumstances a secret.

As Tubman was frequently away from home on rescue missions and the abolition circuit, and would spend extended periods away from home during the Civil War, she entrusted Margaret to the care of Lazette Miller Worden, the sister of Frances Miller Seward. A widow, Worden resided in the Seward home in Auburn. Margaret, according to Alice Brickler, lived

Lydia Maria Child, an abolitionist, served as a member of the American Anti-Slavery

Society’s executive board during the 1840s and 1850s, alongside Lucretia Mott. She also wrote short stories exploring the complex issues of slavery. In a January 1862 letter to John Greenleaf Whittier, Child wrote:

In May 1862, Tubman traveled to South Carolina, where she joined Dr Henry K. Durant, the director of the Freedman’s Hospital at Port Royal. Soldiers as well as fugitives were dying; some of the most common illnesses were typhoid, cholera, malaria, yellow fever, chicken pox and dysentery. Tubman was knowledgeable in local roots to treat diseases; her healing powers became legendary among soldiers.

not as a servant but as a guest within her home. She taught Mother to speak properly, to read, write, sew, do housework and act as a lady. Whenever Aunt Harriet came back, Mother was dressed and sent in the Seward carriage to visit her. Strange to say, Mother looked very much like Aunt Harriet and there was hardness about her character in the face of adversity that must have been hereditary.Lazette Worden met regularly for tea with Martha Coffin Wright. Wright wrote in a letter, “Mrs. Worden was just here—she has taken a contraband 10 yrs. old to live with her, a niece of Harriet Tubman.” These women, along with others, looked out for Harriet Tubman, her parents and extended family.

Lydia Maria Child, an abolitionist, served as a member of the American Anti-Slavery

|

| Lydia Maria Child |

You have doubtless heard of Harriet Tubman, whom they call Moses, on account of the multitude she has brought out of bondage by her courage and ingenuity. She talks politics sometimes, and her uncouth utterance is wiser than the plans of politicians. She said the other day:

"Master Lincoln, he's a great man, and I am a poor negro; but the negro can tell master Lincoln how to save the money and the young men. He can do it by setting the negro free. Suppose that was an awful big snake down there, on the floor. He bite you. Folks all scared, because you die. You send for a doctor to cut the bite; but the snake, he rolled up there, and while the doctor doing it, he bite you again. The doctor dug out that bite; but while the doctor doing it, the snake, he spring up and bite you again; so he keep doing it, till you kill him. That's what master Lincoln ought to know."

|

| Harper's Weekly Illustration of wartime South Carolina |

|

| "Contraband" in South Carolina, 1862 |

|

| David Hunter |

The three States of Georgia, Florida and South Carolina, comprising the military department of the south, having deliberately declared themselves no longer under the protection of the United States of America, and having taken up arms against the said United States, it becomes a military necessity to declare them under martial law. This was accordingly done on the 25th day of April, 1862. Slavery and martial law in a free country are altogether incompatible; the persons in these three States — Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina— heretofore held as slaves, are therefore declared forever free.This order was rescinded by Abraham Lincoln, who was concerned about the political effects that it would have in the Union's border states. Despite Lincoln's concerns that immediate emancipation in the South might drive some slave holding Unionists to support the Confederacy, the national mood was moving against slavery, especially within the Army.

Confederate slave owners had been anxious before the war started that the North's goal was the abolition of slavery; they reacted strongly to the Union effort to emancipate slaves held in the Confederacy. Confederate President Jefferson Davis issued orders to the Confederate States Army that Hunter was to be considered a "felon to be executed if captured."

Undeterred by the president's reluctance and intent on extending freedom to potential black soldiers, Hunter again flouted orders from the federal government and enlisted ex-slaves as soldiers in South Carolina without permission from the War Department. This action incensed border state slave holders: Kentucky Representative Charles Wickliffe sponsored a resolution demanding a response. Hunter sent a sarcastic and defiant letter on June 23, 1862, in which he delivered a stern reminder to the Congress of his authority as a commanding officer in a war zone:

I reply that no regiment of "Fugitive Slaves" has been, or is being organized in this Department. There is, however, a fine regiment of persons whose late masters are "Fugitive Rebels"--men who everywhere fly before the appearance of the National Flag, leaving their servants behind them to shift as best they can for themselves. . . . So far, indeed, are the loyal persons composing this regiment from seeking to avoid the presence of their late owners, that they are now, one and all, working with remarkable industry to place themselves in a position to go in full and effective pursuit of their fugacious and traitorous proprietors. . . . The instructions given to Brig. Gen. T. W. Sherman by the Hon. Simon Cameron, late Secretary of War, and turned over to me by succession for my guidance,--do distinctly authorize me to employ all loyal persons offering their services in defence of the Union and for the suppression of this Rebellion in any manner I might see fit. . . . In conclusion I would say it is my hope,--there appearing no possibility of other reinforcements owing to the exigencies of the Campaign in the Peninsula,--to have organized by the end of next Fall, and to be able to present to the Government, from forty eight to fifty thousand of these hardy and devoted soldiers.The War Department eventually forced Hunter to abandon this scheme, but the government nonetheless moved soon afterward to expand the enlistment of black men as military laborers. Congress approved the Second Confiscation Act in July 1862, which effectively freed all slaves working within the armed forces by forbidding Union soldiers to aid in the return of fugitive slaves.

|

| Ormsby Mitchel |

“Good colored people, you have a great work to do, and you are in a position of responsibility. This experiment is to give you freedom, position, homes, your families, property, your own soil. It seems to me a better time is coming … a better day is dawning.”

~ Ormsby Mitchel

|

| Refuee Cabins in South Carolina |

|

| Thomas Wentworth Higginson |

Who should drive out to see me today but Harriet Tubman, who is living at Beaufort as a sort of nurse and general caretaker.While Tubman was living in the South, she occasionally received letters from her parents, which they dictated to friends who would write and mail them. One of these letter writers was a woman named Sarah Bradford, who met Tubman's mother at church in Auburn.

|

| James Montgomery |

On the morning of June 2, 1863, three steamboats made their way up the river; Montgomery landed a small detachment that drove off several Confederate pickets. Some of the fleeing Confederates rode to the nearby village of Green Pond to sound the alarm. Meanwhile, a company of the 2nd South Carolina under Captain Carver landed two miles above Fields Point at Tar Bluff and deployed into position. The two ships steamed upriver to the Nichols Plantation. Although Confederate troops stationed at Green Pond were notified of the raid, they did not respond at first. During the summer season, because of malaria, typhoid fever and small pox in the Low Country,officers had pulled back most Confederate troops from the rivers and swamps, leaving only small detachments. Montgomery's troops torched William Heyward’s plantation and C.T. Lowndes's rice mill,

|

| Illustration fo Combahee River Raid from Harper's Weekly, July 4, 1863 |

I nebber see such a sight. We laughed, an’ laughed, an’ laughed. Here you’d see a woman wid a pail on her head, rice a smokin’ in it jus’ as she'd taken it from de fire, young one hangin’ on behind, one han’ roun’ her forehead to hold on, t’other han’ diggin’ into de rice-pot, eatin’ wid all its might; hold of her dress two or three more; down her back a bag wid a pig in it. One woman brought two pigs, a white one an’ a black one; we took ‘em all on board; named de white pig Beauregard, and de black pig Jeff Davis. Sometimes de women would come wid twins hangin’ roun’ der necks; ‘pears like I nebber see so many twins in my life; bags on der shoulders, baskets on der heads, and young ones taggin’ behin’, all loaded; pigs squealin’, chickens screamin’, young ones squallin’.”After the boats were filled to capacity and beyond, the throng of escaping slaves still ashore held on to the boats to prevent them from leaving, putting the boats in danger of capsizing. Oarsmen tried beating them on their hands, but the mob would not let go, as they were afraid the gunboats would go off and leave them. The small boats made several trips back and forth to load those who wanted to leave. The Union ships returned to Beaufort the next day. Soldiers took the new freedmen to a resettlement camp.

Due to the efforts in planning and intelligence provided by Tubman and her contacts, more than 750 slaves were freed as a result of Montgomery's raid. Many of the men joined the Union Army. Newspapers reported on Tubman's "patriotism, sagacity, energy, and ability," and she was praised for her recruiting efforts. A reporter from the Wisconsin State Journal, who witnessed the victorious return, wrote:

Col. Montgomery and his gallant band of 300 hundred black soldiers, under the guidance of a black woman [Harriet Tubman], dashed into the enemies’ country, struck a bold and effective blow, destroying millions of dollars worth of commissary stores, cotton, and lordly dwellings, and striking terror to the heart of rebellion, brought off near 800 slaves and thousands of dollars worth of property, without losing a man or receiving a scratch! It was a glorious consummation.In a written report to Secretary Stanton, Union General Rufus Saxton stated

|

| Rufus Saxton |

This is the only military command in American history wherein a woman, black or white, led the raid and under whose inspiration it was originated and conducted.

The Charleston Mercury reported:

We have gathered some additional particulars of the recent destructive Yankee raid along the banks of the Combahee. The latest official dispatch from Gen. WALKER, dated Green Pond, eleven o’clock Tuesday night, and which was received here on Wednesday morning, conveyed intelligence that the enemy had entirely disappeared. It seems that the first landing of the Vandels [sic], whose force consisted mainly of three 'companies, officered by whites, took place at Field Point, on the plantation of Dr. R. L. BAKER, at the mouth of the Combahee River. After destroying the residence and outbuildings, the incendiaries proceeded along the river bank, visiting successively the plantations of Mr. OLIVER MIDDLETON, Mr. ANDREW W. BURNETT, Mr. WM. KIRKLAND, Mr. JOSHUA NICHOLLS, Mr. JAMES PAUL, Mr. MANIGAULT, Mr. CHAS. T. LOWNDES and Mr. WM. C. HEYWARD. After pillaging the premises of these gentlemen, the enemy set fire to the residences, outbuildings and whatever grain, etc., they could find. The last place at which they stopped was the plantation of WM. C. HEYWARD, and, after their work of devastation there had been consummated, they destroyed the pontoon bridge at Combahee Ferry. They then drew off, taking with them between 600 and 700 negros, belonging chiefly, as we are informed, to Mr. WM. C. HEYWARD and Mr. C.T. LOWNDES.

The residences on these plantations are located at distances from the river, varying in different cases from one to two miles. On the plantation of Mr. NICHOLLS between 8000 and 10,000 bushels of rice were destroyed. Besides his residence and outbuildings, which were burned, he lost a choice library of rare books, valued at $10,000. Several overseers are missing, and it is supposed that they are in the hands of the enemy.The dismal Confederate performance at Combahee Ferry led to a formal investigation. Captain John F. Lay filed a lengthy report on June 24; he found the action “mortifying and humiliating to our arms.” In summary he noted:

This raid by a mixed party of blacks and degraded whites seems to have been designed only for plunder, robbery, and destruction of private property; in carrying it out they have disregarded all rules of civilized war, and have acted more as fiends than human beings. Fortunately the planters had removed their families, who thus avoided outrage and insult. The enemy seem to have been well posted as to the character and capacity of our troops and their small chance of encountering opposition, and to have been well guided by persons thoroughly acquainted with the river and the country. Their success was complete, as evidenced by the total destruction of four fine residences, six valuable mills, with many valuable out-buildings (the residence of Mr. Charles Lowndes alone escaped), and large quantities of rice. They also successfully carried off from 700 to 800 slaves of every age and sex. These slaves, it is believed, were invited by these raiders to join them in their fiendish work of destruction. The loss of Messrs. Nickols and Kirkland was very great–an entire loss, including for the former a large and choice library, valued at $15,000.Shortly afterward, Tubman had someone write a letter for her to Franklin Sanborn in Boston, asking for a bloomer dress because long skirts were a handicap on an expedition. Sanborn was at that time editor of The Boston Commonwealth. He made a front page story of the Combahee raid, and Tubman's part in it. It appeared on Friday, July 10, 1863:

Col. Montgomery and his gallant band of 300 black soldiers, under the guidance of a black woman, dashed into the enemy's country, struck a bold and effective blow and brought off near 800 slaves. "Since the rebellion she [Harriet) has devoted herself to her great work of delivering the bondman, with an energy and sagacity that cannot be exceeded. Many and many times she has penetrated the enemy's lines and discovered their situation and condition, and escaped without injury, but not without extreme hazard . . .

She is the most shrewd and practical person in the world, yet she is a firm believer in omens, dreams and warnings.

|

| Robert Gould Shaw |

|

| Norwood Hallowell |

The 54th left Boston with high morale, despite the fact that Jefferson Davis' proclamation of December 23, 1862 effectively put both African-American enlisted men and white officers under a death sentence if captured. The proclamation was affirmed by the Confederate Congress in January 1863, and dictated that black soldiers and their white officers would be turned over to the states from which the enlisted soldiers had been slaves.

The 54th arrived in Beaufort in and joined with the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers led by James Montgomery. The enlisted men of the 54th were recruited on the promise of pay and allowances equal to their white counterparts. This was supposed to amount to subsistence and $14 a month. Instead, they were informed upon arriving in South Carolina that the Department of the South would pay them only $7 per month ($10 with $3 withheld for clothing, while white soldiers did not pay for clothing at all.) Colonel Shaw and many others immediately began protesting the measure. A regiment-wide boycott of the pay tables on paydays became the norm.

|

| Illustration of Battle of Fort Wagner |

|

| Lewis Douglass |

|

| Clara Barton |

The injured blacks were transported to Beaufort, where Tubman provided nursing and

|

| Henry F. Steward of the 54th, who survived the Battle of Fort Wagner, but died of his wounds 2 months later |

"I'd go to de hospital, I would, early eb'ry mornin'. I'd get a big chunk of ice, I would, and put it in a basin, and fill it with water; den I'd take a sponge and begin. Fust man I'd come to, I'd thrash away de flies, an' dey'd rise, dey would, like bees roun' a hive. Den I'd begin to bathe der wounds, an' by de time I'd bathed off three or four, de fire and heat would have melted de ice and made de water warm, an' it would be as red as clar blood. Den I'd go an' git more ice, I would, an' by de time I got to de nex' ones, de flies would be roun' de fust ones, black an' thick as eber."

In this way she worked, day after day, till late at night; then she went home to her little cabin, and made about fifty pies, a great quantity of ginger-bread, and two casks of root beer. These she would hire some contraband to sell for her through the camps, and thus she would provide her support for another day; for this woman never received pay or pension, and never drew for herself but twenty days' rations during the four years of her labors.

At one time she was called away from Hilton Head, by one of our officers, to come to Fernandina, where the men were "dying off like sheep," from dysentery. Harriet had acquired quite a reputation for her skill in curing this disease, by a medicine which she prepared from roots which grew near the waters which gave the disease. Here she found thousands of sick soldiers and contrabands, and immediately gave up her time and attention to them. At another time, we find her nursing those who were down by hundreds with small-pox and malignant fevers. She had never had these diseases, but she seems to have no more fear of death in one form than another. "De Lord would take keer of her till her time came, an' den she was ready to go."

|

| Harriet Tubman |

She has needed disguise so often, that she seems to have command over her face, and can banish all expression from her features, and look so stupid that nobody would suspect her of knowing enough to be dangerous; but her eye flashes with intelligence and power when she is roused.During the war, Tubman was paid only $200 over a period of 3 years. She supported herself by making and selling pies and root beer.

In late 1865, Tubman finally left her wartime responsilibities and headed for home. She stopped on her way to visit Lucretia Mott and

|

| Lucretia Mott and family outside their home |

The last time Harriet was returning from the war, with her pass as hospital nurse, she bought a half-fare ticket, as she was told she must do; and missing the other train, she got into an emigrant train on the Amboy Railroad. When the conductor looked at her ticket, he said, "Come, hustle out of here! We don't carry niggers for half-fare." Harriet explained to him that she was in the employ of Government, and was entitled to transportation as the soldiers were. But the conductor took her forcibly by the arm, and said, "I'll make you tired of trying to stay here." She resisted, and being very strong, she could probably have got the better of the conductor, had he not called three men to his assistance. The car was filled with emigrants, and no one seemed to take her part. The only word, she heard, accompanied with fearful oaths, were, "Pitch the nagur out!" They nearly wrenched her arm off, and at length threw her, with all their strength, into a baggage-car. She supposed her arm was broken, and in intense suffering she came on to New York. As she left the car, a delicate-looking young man came up to her, and, handing her a card, said, "You ought to sue that conductor, and if you want a witness, call on me." Harriet remained all winter under the care of a physician in New York; he advised her to sue the Railroad company, and said that he would willingly testify as to her injuries. But the card the young man had given her was only a visiting card, and she did not know where to find him, and so she let the matter go.Back home in Auburn, David Wright, who was an attorney, wanted to sue the railroad company, but apparently was unable to pursue the case, although it was publicized. Martha Coffin Wright wrote in a November 1865 letter to her daughter:

How dreadful it was for that wicked conductor to drag her out into the smoking car & hurt her so seriously, disabling her left arm, perhaps for the Winter . . . She sitll carries her hand in a sling - it took three of them to drag her out after first trying to wrench her finger and then her arm - She told the man he was a copperhead scoundrel, for which he choked her . . . She told him she didn't thank any body to call her cullud pusson - She wd he called [her] black or Negro - She was as proud of being a black woman as he was of being white.

After the war, Tubman provided a home not only for her aged parents, but for numerous friends and relatives. On their land, they grew fruit and vegetables, and raised chickens, cows and pigs. Harriet hired herself out to clean, cook, and care for her neighbors' children, as well as making baskets to sell. She also worked to raise money for the Freedmen’s Bureau, which had been established to provide education and relief to millions of newly liberated slaves.

Tubman's grandnephew, James Bowley, had been educated to be a schoolteacher; he became an influential figure during Reconstruction in South Carolina. By 1870 he was a school comissioner and owned a small amount of property. He had been elected to the State House of Representatives by 1869, where he served until at least 1874. He was named a trustee of the University of South Carolina in 1873, just as it was to enter a brief phase of integration. However, this all changed again when the Democrats returned to power in 1876 and ended the university's experiment with integrated education.

As Jean M. Humez wrote in her biography, Harriet Tubman: The Life and the Life Stories:

Harriet Tubman appealed to the federal government for pay for her service during the

war; influential friends and community leaders published letters in newspapers advocating for her, believing that she deserved back pay and a veteran’s pension. An Auburn banker prepared a detailed account and documentation of Tubman’s war service and military assignments. The effort to collect pay and/or a pension would go on for years.

Letter from William Seward:Tubman's grandnephew, James Bowley, had been educated to be a schoolteacher; he became an influential figure during Reconstruction in South Carolina. By 1870 he was a school comissioner and owned a small amount of property. He had been elected to the State House of Representatives by 1869, where he served until at least 1874. He was named a trustee of the University of South Carolina in 1873, just as it was to enter a brief phase of integration. However, this all changed again when the Democrats returned to power in 1876 and ended the university's experiment with integrated education.

As Jean M. Humez wrote in her biography, Harriet Tubman: The Life and the Life Stories:

In the postwar period, the stark moral and religious touchstone issue of human enslavement had vanished along with emancipation. There was no national consensus on how the newly emancipated population would be integrated into the economic, political and social life of the United States after the war was over. Indeed, there was no national consensus on what shape the new United States itself would take, now that the states formerly in rebellion had been defeated by military force but not persuaded of the rightness of the Union's cause.In Maryland, John Tubman was shot and killed in 1867 in an argument with a white man. Although his 13-year old son witnessed the murder by Robert Vincent, The Baltimore American wrote that "it was universally conceded that he would be acquitted" because the only witness was not white. The all-white jury deliberated for ten minutes and returned a verdict of not guilty.

Harriet Tubman appealed to the federal government for pay for her service during the

|

| Harriet Tubman |

WASHINGTON, July 25, 1868.

MAJ.-GEN. HUNTER--

My DEAR SIR: Harriet Tubman, a colored woman, has been nursing our soldiers during nearly all the war. She believes she has a claim for faithful services to the command in South Carolina with which you are connected, and she thinks that you would be disposed to see her claim justly settled.

I have known her long, and a nobler, higher spirit, or a truer, seldom dwells in the human form. I commend her, therefore, to your kind and best attentions.

Faithfully your friend,

WILLIAM H. SEWARD

In an attempt to raise money for Tubman and alleviate the family's poverty, Sarah Hopkins

Bradford began interviewing Tubman for an authorized biography. Although Bradford had not been close to Tubman, and knew few of her friends and colleagues, she wrote to people who had worked with Tubman in the Underground Railroad and the military. Frederick Douglass wrote a letter to honor Tubman and be included in the book:

Rochester, August 29, 1868

Dear Harriet:

I am glad to know that the story of your eventful life has been written by a kind lady, and that the same is soon to be published. You ask for what you do not need when you call upon me for a word of commendation. I need such words from you far more than you can need them from me, especially where your superior labors and devotion to the cause of the lately enslaved of our land are known as I know them. The difference between us is very marked. Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day – you in the night. I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes of being approved by the multitude, while the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scarred, and foot-sore bondmen and women, whom you have led out of the house of bondage, and whose heartfelt, “God bless you,” has been your only reward. The midnight sky

and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism. Excepting John Brown – of sacred memory – I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people than you have. Much that you have done would seem improbable to those who do not know you as I know you. It is to me a great pleasure and a great privilege to bear testimony for your character and your works, and to say to those to whom you may come, that I regard you in every way truthful and trustworthy.

Harriet Tubman's Escape by Jacob Lawrence

Your friend,

Frederick Douglass.

Thomas Garret also wrote a letter to be included in the book:

WILMINGTON, 6th Mo., 1868.

MY FRIEND:

Thy favor of the 12th reached me yesterday, requesting such reminiscences as

Thomas Garrett