|

| "I am not merely satisfied in making money for myself for I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of women of my race." |

Robert W. Burney's land was confiscated by Union soldiers in 1865, but Breedlove’s

|

| The Breedlove cabin, Delta, Louisiana |

In 1874, when she would have entered first grade, public schools for black children in Louisiana were closed after the legislature refused to fund them and the Freedman’s Bureau disbanded its education division. Three years later, federal troops left the former Confederate states; their absence opened the way for a reign of terror that drove thousands of blacks from the South. The Breedlove brothers headed west, part of the "Exoduster" movement.

Exodusters was a name given to blacks who migrated from Southern states after Reconstruction ended and Southern racists took over the local governments again. The number one cause of black migration out of the South at this time was to escape the Ku Klux Klan, the White League, and the Black Codes, which not only legally and financially made second-class citizens of African Americans, but threatened their safety with violence and terrorism. The Exodusters were more than migrants; they can more accurately be regarded as refugees.

Willie and Louvenia Powell, along with Sarah, moved across the Mississippi River to Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1877. Sarah picked cotton, washed clothes, and did housework. She married a man named Moses McWilliams, later saying that "I married at the age of fourteen in order to get a home of my own." On June 6, 1885, Sarah gave birth to a daughter, Leila.

Moses died two years later, when Sarah was 20, and Lelia was just 2 years old. No documentation exists for the causes of death for her parents or husband.

Early in 1889, Sarah McWilliams and her daughter moved to St. Louis, Missouri where three of her brothers, Alexander, James and Solomon, lived and worked as barbers. She managed to get work as a laundry woman, earning about a dollar a day.

The St. Louis neighborhood where Sarah and her family lived was a place so dangerous that local police called it “the Bad Lands.” There were many saloons, brothels, and cheap bathhouses. Sarah joined St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, which, like other black churches of the time, had a congregation of helpful people who offered her leads on jobs, advice on comportment, and some financial help. She put Lelia, not yet five, into the hands of the St. Louis Colored Orphans Home for part of the week while she worked as a washerwoman. As Lelia was considered to be half-orphaned, it was not unusual for single mothers to get such assistance from homes for orphans.

On August 11, 1894, Sarah married her second husband, John Davis. He turned out to be a heavy drinker, financially unreliable and unfaithful to her. As the breadwinner of the family, Sarah worked hard and struggled to provide for her daughter. In her late twenties, her began hair to fall out, a condition probably owing to a combination of inadequate hygiene and stress.

Moses died two years later, when Sarah was 20, and Lelia was just 2 years old. No documentation exists for the causes of death for her parents or husband.

|

| St. Louis, Missouri |

The St. Louis neighborhood where Sarah and her family lived was a place so dangerous that local police called it “the Bad Lands.” There were many saloons, brothels, and cheap bathhouses. Sarah joined St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, which, like other black churches of the time, had a congregation of helpful people who offered her leads on jobs, advice on comportment, and some financial help. She put Lelia, not yet five, into the hands of the St. Louis Colored Orphans Home for part of the week while she worked as a washerwoman. As Lelia was considered to be half-orphaned, it was not unusual for single mothers to get such assistance from homes for orphans.

On August 11, 1894, Sarah married her second husband, John Davis. He turned out to be a heavy drinker, financially unreliable and unfaithful to her. As the breadwinner of the family, Sarah worked hard and struggled to provide for her daughter. In her late twenties, her began hair to fall out, a condition probably owing to a combination of inadequate hygiene and stress.

Lelia attended public schools in St. Louis, but her attendance and grades were spotty. When Lelia was 17, Sarah managed to send her to Knoxville College in Tennessee, where in spite of her age, she was admitted as a 7th grade student, rather than being enrolled in a college curriculum. The college offered high school classes as well as college. Knoxville College was rooted in a mission school established by the Presbyterian Church to educate the city's free blacks and freed slaves.In the 1870s, the church's Freedmen's Mission, decided to refocus its efforts on building a larger, better-equipped school in Knoxville. The school's first building was completed in 1876 and the school at the end of the year. The new school was primarily a training school for teachers, but also operated an academy for the education of local children.

By this time, three of Sarah's brothers, Solomon, James and Alexander, had died of heart disease or tuberculosis. Only Sarah, Louvenia and Owen were still alive. Owen, however, had abandoned his second wife, Lucy, and four daughters in Denver, Colorado, and his whereabouts were unknown.

After about ten years after their wedding, John Davis claimed that Sarah had deserted him and he moved in with his girlfriend, Susie. Around the same time, Sarah began seeing Charles Joseph (“C.J.”) Walker, an advertising salesman for the St. Louis Clarion. She also attended public night school whenever she could.

Sarah's life began to change when she discovered the “The Great Wonderful Hair Grower” of

Annie Turnbo-Pope (later Malone), an African American women from Illinois who had relocated her hair care business to St. Louis. After using Turnbo’s products with success, Sarah began selling them as a local agent, working on commission.

Annie Minerva Turnbo had been born in Illinois, the daughter of escaped slaves. Robert Turnbo enlisted with the Union troops in the Civil war, while her mother stayed with the children in Illinois. Annie Turnbo was the 10th of 11 children; she was born in 1867, the same year as Sarah Breedlove. She was also orphaned at a young age as Sarah had been, and was also taken in by an older sister. Annie, however, was able to attend public schools in Illinois. She often practiced hairdressing with her sister, and began to develop her own hair care products. She called one product “Wonderful Hair Grower, ” and sold it door-to-door in Peoria.

By this time, three of Sarah's brothers, Solomon, James and Alexander, had died of heart disease or tuberculosis. Only Sarah, Louvenia and Owen were still alive. Owen, however, had abandoned his second wife, Lucy, and four daughters in Denver, Colorado, and his whereabouts were unknown.

After about ten years after their wedding, John Davis claimed that Sarah had deserted him and he moved in with his girlfriend, Susie. Around the same time, Sarah began seeing Charles Joseph (“C.J.”) Walker, an advertising salesman for the St. Louis Clarion. She also attended public night school whenever she could.

Sarah's life began to change when she discovered the “The Great Wonderful Hair Grower” of

|

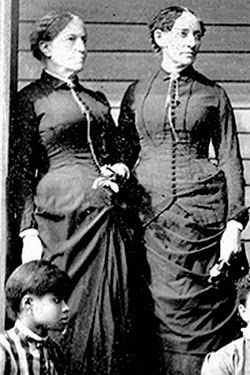

| Annie Turnbo |

Annie Minerva Turnbo had been born in Illinois, the daughter of escaped slaves. Robert Turnbo enlisted with the Union troops in the Civil war, while her mother stayed with the children in Illinois. Annie Turnbo was the 10th of 11 children; she was born in 1867, the same year as Sarah Breedlove. She was also orphaned at a young age as Sarah had been, and was also taken in by an older sister. Annie, however, was able to attend public schools in Illinois. She often practiced hairdressing with her sister, and began to develop her own hair care products. She called one product “Wonderful Hair Grower, ” and sold it door-to-door in Peoria.

Annie Turnbo moved to St. Louis in 1092, where she and three hired assistants sold her hair care products from door-to-door. As part of her marketing, she gave away free treatments to attract more customers. In 1903 she briefly married a Mr. Pope but soon divorced him. Her products were sold under the name of "Roberts and Pope," as for a time she had a partner named L. L. Roberts. In 1904, Turnbo-Pope opened her first shop, and also launched an advertising campaign in the black press, held news conferences, toured many southern states, and recruited many women whom she trained to sell her products. St. Louis at the time held the fourth largest population of African Americans. While in St. Louis, she copyrighted her Poro brand beauty products. Her publicity materials said that "Poro" was a West African word meaning physical and spiritual growth.

In July 1905, Sarah McWilliams moved to Denver, Colorado, where her sister-in-law, Lucy Breedlove, and four nieces lived. At first, her primary job was as a cook in a boarding house; she also sold Annie Turnbo-Pope's hair products. Within a year, she had saved enough money to resign from her job and sold haircare products door-to-door. C.J. Walker came to Denver, and they married on January 4, 1906.

Mrs. Sarah Walker, probably at the prompting of her new husband, who had worked in

newspaper advertising, paid to print a letter in Denver's newspaper, The Statesman, warning customers not to buy imitation products:

newspaper advertising, paid to print a letter in Denver's newspaper, The Statesman, warning customers not to buy imitation products:

I wish to say to my customers to not be led into buying of [another hair culturist] and think you are buying the grower I represent, Roberts and Pope. I represent the preparation bearing the label of Roberts and Pope and it can be secured only from me.

Mrs. C.J. WalkerWithin months, however, she began advertising a "Wonderful Hair Grower," product of "Madam C.J. Walker." She later claimed that she had a dream:

A big black man appeared to me and told me what to mix up for my hair. Some of the remedy was grown in Africa, but I sent for it, put it on my scalp, and in a few weeks my hair was coming in faster than it had ever fallen out.According to A'Lelia Bundles, in her biography of Madam Walker, On Her Own Ground:

Pope-Turnbo - and later Sarah - made much of their proprietary mixtures, but the real secret was a regimen of regular shampoos, scalp massage, nutritious food, and an easily duplicated, sulfur-based formula that neither of them had originated.The new Madam Walker traveled around Colorado, from Pueblo to Trinidad to Colorado Springs and and back to Denver, selling her hair care products and training students in her treatment course. Later, C.J. Walker tried to take the credit for the business, saying

I alone am responsible for the successful beginning of this business. Otherwise the Mmd. would have taken the road for the Poro people.In August, her daughter Lelia McWilliams arrived in Denver; she had taken a hair growing course in St. Louis in order to assist her mother. They ran a small salon in the city. Lelia ran the salon while Sarah traveled with her husband, lecturing, giving treatments, and developing a mail order business. Annie Pope-Turnbo, having become aware of what was going on, had a letter printed in The Statesman:

The proof of the value of our work is that we are being imitated and largely by persons whose own hair we have actually grown. . . . They have very frequently mentioned us when trying to sell their goods (saying that theirs is the same or just as good). . . . BEWARE OF IMITATIONS.

By May 1907, there was an announcement in The Statesman that Annie Pope-Turnbo had sent a new agent to Denver; a short time later, there was another announcement that Madam Walker and Miss McWilliams were closing their Denver hair parlor in order to open a business in another city. Denver had a small black population, and the Walkers believed that they could do even better in the Northeastern United States.

In 1907, Sarah had sales of $3,652, which was almost three times her total 1906 earnings while she was still working as a Roberts-Pope agent. (The relative purchasing power of $3,652 in today's money would be around $100,000.) Most working black women made only between $100-250 a year as domestic servants; white men who worked in factories made $500-700 a year.

|

| Lelia College |

C.J. and Sarah Walker moved to Indianapolis, Indiana in 1910, and eventually purchased a

|

| The Walker home in Indianapolis |

As Madam Walker continued to travel, publicize her products and company, and train hair culturists, "Walker Agents" became well known throughout the black communities of the United States. They were encourage to promote Walker's philosophy of "cleanliness and loveliness" as a means of advancing the status of African-Americans. She developed a “Special Correspondence Course” business, founded on her System of Beauty Culture. By the end of 1910, her annual income was $10, 989, nearly three times what it had been in 1907.

In September 1911, with her attorney Freeman Ransom's assistance, Madam Walker petitioned the Indiana Secretary of State to become incorporated and the petition was granted. The Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company of Indiana, Inc. began: Sarah Walker was the President and sole shareholder of all 1,000 shares of stock.

Lelia, whose husband had left her within a year of their wedding, began calling herself "Mrs. Lelia Walker Robinson."

|

| Madam Walker and Lelia in their chaffeur-driven car |

During a visit to the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1912, Madam Walker introduced herself to Booker T. Washington. Booker Taliaferro Washington was the dominant African American leader in the country between 1890 and 1915. He had been born in slavery in 1856, and had become the leading voice of former slaves and their descendants. In 1895 his "Atlanta Compromise" called for avoiding confrontation over segregation and instead putting more reliance on long-term educational and economic advancement in the black community. His message was that it was not the time to challenge segregation and the disfranchisement of black voters in the South. He mobilized a nationwide coalition of middle-class blacks, church leaders, and white philanthropists and politicians.

While in Alabama, Madam Walker promoted her company, sold products, gave treatments, and recruited and trained more Walker agents in hair growing and hair care methods. In Tuskegee, she opened an agency near the campus; the Walker representative was Dora Larrie, an Indianapolis woman. Her husband, C.J. Walker had an affair with Larrie, who pressured him to leave Madam Walker and go into business with her. Larrie left Alabama and traveled with C.J. Walker to Atlanta, Georgia. Madam Walker learned of their affair and decided to divorce him. Her attorney, Freeman Ransom, began the legal proceedings.

While in Alabama, Madam Walker promoted her company, sold products, gave treatments, and recruited and trained more Walker agents in hair growing and hair care methods. In Tuskegee, she opened an agency near the campus; the Walker representative was Dora Larrie, an Indianapolis woman. Her husband, C.J. Walker had an affair with Larrie, who pressured him to leave Madam Walker and go into business with her. Larrie left Alabama and traveled with C.J. Walker to Atlanta, Georgia. Madam Walker learned of their affair and decided to divorce him. Her attorney, Freeman Ransom, began the legal proceedings.

|

| Madam Walker |

No matter how deep my hurt, I always smiled. I refused to be discouraged, for neither God nor man can use a discouraged person.Later the same year, Madam Walker attended the National Negro Business League (NNBL)

|

| Booker T. Washington |

Surely you are not going to shut the door in my face. I feel that I am in a business that is a credit to the womanhood of our race. I am a woman who started in business seven years ago with only $1.50 . . . .This year (up to the 19th day of this month ) I had taken in $18,000. (Prolonged applause). This makes a grand total of $63,049 made in my hair business in Indianapolis. (Applause.)

I went into a business that is despised, that is criticized and talked about . . . I have been trying to get before you business people to tell you what I am doing. I am a woman that came from the cotton fields of the South; I was promoted from there to the wash-tub (laughter); then I was promoted to the cook kitchen, and from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. . . .

I am not ashamed of my past; I am not ashamed of my humble beginning. Don't think that because you have to go down in the wash-tub that you are any less a lady! (prolonged applause.)

Everybody told me I was making a mistake by going into this business . . . I have built my own factory . . . I employ in that factory seven people, including a bookkeeper, a stenographer, a cook and a house girl . . . I own my ownShortly after she returned from Chicago, Freeman Ransom filed papers for her divorce from C.J. Walker. The proceedings were complicated by the fact that there was no existing marriage license for the Walker marriage in Denver, and no divorce papers in St. Louis for her second marriage to John Davis. Because Ransom had evidence for C.J. Walker's adultery, he was able to get a final divorce decree for his client. C.J. Walker attempted to go into business with his family members, including his new wife, Dora Larrie, who he married in March 1913. However, his business floundered, and he soon tried to reconcile with Madam Walker. In March 1914, in a letter of public apology in the Indianapolis Freeman newspaper in March 1914, he wrote of Dora Larrie:

Madam Walker at the wheel of her automobile

automobile . . . Now, my object in life is not simply to make money for myself or to spend it on myself in dressing or running around in an automobile . . . I love to use a part of what I make in trying to help others.

We were not married long before I discovered she did not love me, but that she only wanted the title Mme., and the formula.He said that "drink and this designing evil woman" had come between him and Madam Walker. He wrote to his ex-wife asking for money and work. Freeman Ransom, as Madam Walker's attorney, sent him $35 and suggested he go to Key West, Florida: "keep sober and build up a big business." C.J. continued to write to his ex-wife for the rest of his life: "I am writing these lines with tears dripping from my eyes."

|

| Fairy Mae Bryant |

|

| Lelia in 1913 |

The Walker business continued to grow. Freeman Ransom wrote to Lelia in 1913 that

Madam is in a fair way to be the wealthiest colored person in America. I am ambitious that she be just that. . . . You will help me, won't you? . . . I want you to join me in urging Madam to bank a large portion of her money to the end that it be accumulating and drawing interest for possible rainy days.In July 1913, Madam was thrilled when Booker T. Washington agreed to be her houseguest during his visit to Indianapolis. Later that year, at the Fourteenth Annual Convention of the National Negro Business League held in Philadelphia, Madam Walker was on the schedule, explaining to the audience how she had succeeded in the business world:

In the first place I found, by experience, that it pays to be honest and straightforward in all your dealings. (Applause.) In the second place, the girls and women of our race must not be afraid to take hold of business endeavor and, by patient industry, close economy, determined effort, and close application to business, wring success out of a number of business opportunities that lie at their doors. . . .

I have made it possible for many colored women to abandon the wash-tub for more pleasant and profitable occupation. (Hearty applause.) Now I realize that in the so-called higher walks of life, many were prone to look down upon "hair dressers" as they called us; they didn't have a very high opinion of our calling, so I had to go down and dignify this work, so much so that many of the best women of our race are now engaged in this line of business, and many of them are now in my employ.

Madam Walker with Booker T. Washington in Indianapolis

|

| A Poro College Graduating Class |

Walker hired an architect to draw up plans for a new building to house the Walker business; she intended that the building, covering a whole city block, could serve as a social and cultural center for the African-American community in Indianapolis. A theater in the new building would welcome African Americans. In addition to Annie Turnbo-Malone's example, she was also angered by an incident that occurred during a visit to a theater in Indianapolis. Madam Walker, who loved going to the movies, went to the Isis Movie Theater and gave the ticket seller a dime, the standard admission. The agent pushed the coin back across the counter, saying that the price had gone up to 25 cents for "colored persons." Walker immediately asked Freeman Ransom to sue the theater. In his complaint to the Marion County Court, he demanded $100 in damages for racial discrimination in a public place.

|

| The Harlem townhouse |

In the fall of 1913, Madam Walker traveled throughout the Caribbean promoting her business and recruiting others to teach her hair care methods. She visited Jamaica, Haiti, Costa Rica, Panama and Cuba. While her mother traveled, Lelia helped facilitate the purchase of property in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, recognizing that the area would be an important base for future business operations. The Harlem townhouse and Walker Salon were designed by Vertner Tandy, the first licensed black architect in New York State. “There is nothing to equal it,” Lelia wrote to Ransom. "Not even on Fifth Avenue.”

At the August 1914 NNBL convention in Muskogee, Oklahoma, Booker T. Washington invited Madam Walker to speak from the platform again:

I am not merely satisfied in making money for myself. I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of women of my race.

. . . I had little or no opportunity when I started out in life . . . I had to make my own living and my own opportunity. But I made it. That is why I want to say to every Negro woman present, don't sit down and wait for the opportunities to come, but you have to get up and make them!

. . . If the truth were known there are many women who are responsible for the success of you men.Like many wealthy people, Madam Walker received many requests for money from family, acquaintances and strangers. She supported her sister-in-law, Lucy Breedlove and four nieces in Denver, and her sister, Louvenia Breedlove Powell, who had moved to Indianapolis.

It seems the more I do for my people they are harder to please and I am going to quit trying to please them.In 1915 she sponsored a benefit concert for 16-year-old Frances Spencer, a talented black harpist. Walker presented Spencer with a $300 check for the down payment on a harp, but was unsettled by the girl's request to come live with her in her home. Spencer continued to ask until Walker allowed her to move in.

After remaining here for about two months and being treated like one of my own family and receiving a salary of $6 a week . . . she stole out everything which she had, including the harp. . . Now I want to say, and this is final, that I am through helping so-called people. . . . There isn't a day that I am not besieged by people for help . . . and, near as I could, I have tried to help, or reach them in some way. In the future all appeals will be turned down and consigned to the waste basket.In 1915, Madam Walker took an extended business trip West with Mae, stopping in St. Louis and Denver on her way to California, Washington and Oregon. They also enjoyed visits to Yellowstone National Park in California and the Grand Canyon in Arizona. Her lectures at this time were illustrated by slides showing her hair care system, and also the accomplishments of African Americans in business and education.

|

| Booker T. Washington's Funeral |

1915 was the year that the film, The Birth of a Nation, directed by D.W. Griffith, was a commercial success in the United States. It was was highly controversial owing to its portrayal of black men (played by white actors in blackface) as unintelligent and sexually aggressive towards white women. The Ku Klux Klan was presented as a heroic force in the South. There were widespread African-American protests against the film; the NAACP, which had been founded just a few years earlier, spearheaded an unsuccessful campaign to ban the film. Riots broke out in major cities, including Boston and Philadelphia, and it was denied release in some other cities (Chicago, Denver, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Minneapolis). Gangs of whites roamed city streets attacking blacks. In Lafayette, Indiana, a white man killed a black teenager after seeing the movie. Thomas Dixon, the author of the novel, The Clansman, which the film was based on, reveled in its triumph:

The real purpose of my film was to revolutionize Northern audiences that would transform every man into a Southern partisan for life.Woodrow Wilson and Thomas Dixon had become friends while they were classmates at Johns Hopkins University in the 1880s. The president requested a special screening at the White House for the members of his Cabinet and their families; it was the first film to be shown in the White House. After seeing the film, Wilson reportedly remarked:

|

| Woodrow Wilson |

It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.Born in Virginia in 1856, Wilson was the son of Joseph Ruggles Wilson, a Presbyterian minister who defended slavery and published one of his sermons as Mutual Relation of Masters and Slaves as Taught in the Bible:

This recognition of involuntary servitude is, we say, thus found imbedded in the very heart of the moral law itself-- that law which determines the principles of divine administration over men--a law which constitutes, if I may so speak, the very constitution of that royal kingdom whose regulations begin and end in the infinite holiness of Jehovah, and whose spread through the universal heart of the race is the aim of all Scripture.

. . . But my hearers, if you wish for further conviction, carry your belief of the essential rightness of slavery to the injunctions of our text, which the Apostle publishes for its conservation and perfection. He as much as says, that it is unnecessary to fear that this long-cherished institution will first give way before the enemies who press upon it from without.

If slaveholders preserve it as an element of social welfare, in the spirit of the Christian religion, throwing into it the full measure of gospel-salt allotted to it, and casting around it the same guardianship with which they would protect their family peace, if threatened on some other ground--they need apprehend nothing but their own dereliction in duty to themselves and their dependent servants.

I mean, simply, that while we ought to allow no malignant interference from any quarter with the institution of which we are God's appointed guardians, and while we ought to be suitably alive to any threat of presumptuous violence which may seek to wrest from us our heaven-given rights in our heaven-allowed property--yet, after all, the wisdom which lies underneath the spirit of this sensitive watchfulness of our political zeal, and which gives to that zeal its purity and power, is the wisdom to be exercised in making our domestic servitude all that it should become, so as to render it worth the expenditure of every energy of defence.

We must see to it, that masters and servants understand and appreciate their mutual relation, and that they maintain it on both sides as Christians. . . .

To vital goodness alone belongs the privilege of understanding and administering the whole authority of a masterhood so responsible.

And, oh, when that welcome day shall dawn, whose light will reveal a world covered with righteousness, not the least pleasing sight will be the institution of domestic slavery, freed from its stupid servility on the one side and its excesses of neglect or severity on the other, and appearing to all mankind as containing that scheme of politics and morals, which, by saving a lower race from the destruction of heathenism, has, under divine management, contributed to refine, exalt, and enrich its superior race!Reverend Wilson wrote that "We should begin to meet the infidel fanaticism of our infatuated enemies upon the elevated ground of the divine warrant for the institution." Wilson's father served as a chaplain in the Confederate army during the Civil War; he taught his son the justification of the South's secession from the Union. Woodrow Wilson said in a 1909 speech that his earliest memory was of hearing that Abraham Lincoln had been elected

|

| Robert E. Lee, 1870 |

In the presidential campaign of 1912, Wilson had promised African-Americans “not more grudging justice but justice executed with liberality and cordial good feeling.” When Wilson entered the White House in 1913, Washington, D.C. was a rigidly segregated town — except for federal government agencies. They had been integrated during the post-war Reconstruction period, enabling African-Americans to obtain federal jobs and work side by side with whites in government agencies. Wilson promptly authorized members of his cabinet to reverse this long-standing policy of racial integration in the federal civil service. Cabinet heads – including Albert Burleson, the

postmaster general, and Woodrow Wilson' son-in-law, Secretary of the Treasury William McAdoo of Tennessee – re-segregated facilities such as restrooms and cafeterias in their buildings. In some federal offices, screens were set up to separate white and black workers. African-Americans found it difficult to secure high-level civil service positions, which some had held under previous Republican administrations. The House of Representatives passed a law making racial intermarriage a felony in the District of Columbia. Photographs were required of all applicants for federal jobs. When pressured for a response by black leaders, Wilson replied,

|

| William McAdoo |

The purpose of these measures was to reduce the friction. . . It is as far as possible from being a movement against the Negroes. I sincerely believe it to be in their interest.

A delegation of black professionals led by Monroe Trotter, a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Harvard and Boston newspaper editor, appeared at the White House to protest the new policies. The encounter made front-page news, and subsequent rallies protested Wilson’s treatment of Trotter. Wilson declared that “segregation is not a humiliation but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen.” The Crisis magazine, the official magazine of the NAACP, edited by W.E.B. Dubois, reported:

Mr. Monroe Trotter. Mr. President, we are here to renew our protest against the segregation of colored employees in the departments of our National Government. We [had] appealed to you to undo this race segregation in accord with your duty as President and with your pre-election pledges to colored American voters. We stated that such segregation was a public humiliation and degradation, and entirely unmerited and far-reaching in its injurious effects. . .

President Woodrow Wilson. The white people of the country, as well as I, wish to see the colored people progress, and admire the progress they have already made, and want to see them continue along independent lines.

There is, however, a great prejudice against colored people. . . . It will take one hundred years to eradicate this prejudice, and we must deal with it as practical men.

Segregation is not humiliating, but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen. If your organization goes out and tells the colored people of the country that it is a humiliation, they will so regard it, but if you do not tell them so, and regard it rather as a benefit, they will regard it the same. The only harm that will come will be if you cause them to think it is a humiliation.

Mr. Monroe Trotter. It is not in accord with the known facts to claim that the segregation was started because of race friction of white and colored [federal] clerks. The indisputable facts of the situation will not permit of the claim that the segregation is due to the friction. It is untenable, in view of the established facts, to maintain that the segregation is simply to avoid race friction, for the simple reason that for fifty years white and colored clerks have been working together in peace and harmony and friendliness, doing so even through two [President Grover Cleveland] Democratic administrations. Soon after your inauguration began, segregation was drastically introduced in the Treasury and Postal departments by your appointees.

President Woodrow Wilson. If this organization is ever to have another hearing before me it must have another spokesman. Your manner offends me.After the shouting match that followed, Trotter was ordered out of the White House. Trotter stood outside on the White House grounds and held a press conference, describing what had happened. Monroe Trotter was a newspaper editor and real estate businessman based in Boston, Massachusetts. He was an opponent of the conciliatory race policies of Booker T. Washington, and in 1901 founded the Boston Guardian, an independent African-American newspaper to express that opposition. He contributed to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Born into a well-to-do family, he earned his undergraduate and graduate degrees at Harvard University and was the first man of color to earn a Phi Beta Kappa Key there. Seeing an increase in segregation in northern facilities, he began his work as a civil rights activist.

As the nineteenth century draws to its close it is impossible not to contrast the political ideals now dominant with those of the preceding era. It was the rights of man which engaged the attention of the political thinkers of the eighteenth century. . . Government, it was plainly seen, had become the vehicle of oppression; and the methods by which it could be subordinated to the needs of individual development, and could be made to foster liberty rather than to suppress it, were the favorite study of the most enlightened philosophers. . . .

Humanity was exalted above human institutions, man was held superior to the State, and universal brotherhood supplanted the ideals of national power and glory.

These eighteenth-century ideas were the soil in which modern Liberalism flourished. Under their influence the demand for Constitutional Government arose. Rulers were to be the servants of the people, and were to be restrained and held in check by bills of rights and fundamental laws which defined the liberties proved by experience to be most important and vulnerable. . .

Freed from the vexatious meddling of governments, men devoted themselves to their natural task, the bettering of their condition, with the wonderful results which surround us.

But it now seems that its material comfort has blinded the eyes of the presentgeneration to the cause which made it possible. . . . In our country recent events show how much ground has been lost.

"Gilded Age" Cartoon

The Declaration of Independence no longer arouses enthusiasm; it is an embarrassing instrument which requires to be explained away. The Constitution is said to be “outgrown”; and at all events the rights which it guarantees must be carefully reserved to our own citizens, and not allowed to human beings over whom we have purchased sovereignty.

The great party which boasted that it had secured for the negro the rights of humanity and of citizenship, now listens in silence to the proclamation of white supremacy and makes no protest against the nullifications of the Fifteenth Amendment.

Nationalism in the sense of national greed has supplanted Liberalism. It is an old foe under a new name. By making the aggrandizement of a particular nation a higher end than the welfare of mankind, it has sophisticated the moral sense of Christendom.

Aristotle justified slavery, because Barbarians were “naturally” inferior to Greeks, and we have gone back to his philosophy. We hear no more of natural rights, but of inferior races, whose part it is to submit to the government of those whom God has made their superiors.

The old fallacy of divine right has once more asserted its ruinous power, and before it is again repudiated there must be international struggles on a terrific scale.Madam Walker moved to New York City in 1916, leaving the day-to-day operations of the company in Indianapolis to Freeman Ransom as general manager and to Alice Kelly, her factory forelady. Walker continued to oversee the business from the New York office. Her sister, Louvenia Powell, worked in the Indianapolis factory. Her nieces, Thirsapen Breedlove and Anjetta Breedlove, had an agency in Los Angeles.

|

| The Harlem Salon |

It is just impossible for me to describe it to you . . . It beats anything I have seen anywhere even in the best hair parlors of the whites . . . There is nothing equal to it, not even on Fifth Avenue. . . .Now, Mr. Ransom, in regards to this house, you will agree with Lelia when she said that it would be a monument to us both.In addition to the business, the new townhouse had lavish living and entertainment spaces.

|

| Lelia's bedroom in townhouse |

As regards my coming back to Indianapolis, Mr. Ransom, that is clear out of the question . . . I will never come back to Indianapolis . . . There is so much more joy living in New York where there are not so many narrow, mean people.In the fall of 1916, Mae Walker enrolled at Spelman Seminary in Atlanta. Originally called the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, it had been established in 1881 by two white teachers from Massachusetts, Harriet Giles and Sophia Packard. They had traveled to Atlanta

|

| Harriet Giles and Sophia Packard |

Madam Walker continued to work hard to promote her business in advertising, lectures and interviews, saying:

The NAACP approached her for a contribution to their first major anti-lynching campaign; her contribution was acknowledged publicly by Oswald Garrison Villard, the first NAACP board chairman and grandson of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Blacks in the country continued to be terrorized by hanging, burnings, drownings, shooting, brandings and mutilations that often were witnessed and even photographed by large mobs of whites.

Although rape is often cited as a reason for lynching, statistics show that only about one-fourth of lynchings from 1880 to 1930 were prompted by an accusation of rape. Most victims of lynching were political activists, labor organizers or black men and women who violated white expectations of black deference, and were deemed "uppity" or "insolent." Lynching was closely related to the practice of racial cleansing. The Harrison race riots of 1905 and 1909 in Harrison, Arkansas in Boone County effectively drove all but one African American from the area—creating, through violence and intimidation, a virtually all-white community. Only one person was killed during the riots, in 1905, but the fear of lynching, especially in 1909, motivated black residents to flee. Municipalities throughout Arkansas forbade black people from living in a particular town, usually through campaigns of intimidation. Such “sundown towns” as Alix were far more prevalent in the northern half of Arkansas (where more than 100 such towns existed) than in the rest of the state. In northern and western Arkansas, some entire counties, such as Boone and Polk, refused to allow black residents. Sundown towns were at their peak in the late 1960s, thus surviving long after incidents of had declined.

Occasionally, lynching was sanctioned by Arkansas leaders, who inflamed racial passions as

a means of achieving their own political ends. Arkansas governor Jeff Davis, who served as governor of the state from 1901 to 1907, was quite willing to defend the practice of lynching. When President Theodore Roosevelt visited Arkansas in 1905, Davis famously remarked,

Having a good article for the market is one thing, and putting it properly before the public is another . . .

Agents are engaged in promoting "The Walker System." I feel that I have done something for the race by making it possible for so many colored women and girls to make money.

|

| Oswald Garrison Villard |

Although rape is often cited as a reason for lynching, statistics show that only about one-fourth of lynchings from 1880 to 1930 were prompted by an accusation of rape. Most victims of lynching were political activists, labor organizers or black men and women who violated white expectations of black deference, and were deemed "uppity" or "insolent." Lynching was closely related to the practice of racial cleansing. The Harrison race riots of 1905 and 1909 in Harrison, Arkansas in Boone County effectively drove all but one African American from the area—creating, through violence and intimidation, a virtually all-white community. Only one person was killed during the riots, in 1905, but the fear of lynching, especially in 1909, motivated black residents to flee. Municipalities throughout Arkansas forbade black people from living in a particular town, usually through campaigns of intimidation. Such “sundown towns” as Alix were far more prevalent in the northern half of Arkansas (where more than 100 such towns existed) than in the rest of the state. In northern and western Arkansas, some entire counties, such as Boone and Polk, refused to allow black residents. Sundown towns were at their peak in the late 1960s, thus surviving long after incidents of had declined.

Occasionally, lynching was sanctioned by Arkansas leaders, who inflamed racial passions as

|

| Jeff Davis |

We have come to a parting of the way with the Negro. If the brutal criminals of that race…lay unholy hands upon our fair daughters, nature is so riven and shocked that the dire compact produces a social cataclysm.The Tuskegee Institute began to assiduously document lynchings in 1888, a practice it would continue until 1968. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the black journalist, was outraged in 1889 when three of her friends in Memphis, Tennessee were lynched for opening a grocery that competed with a white-owned store. The murder of her friends drove Wells to research and document lynchings and their causes. She began the process of investigative journalism, looking at the charges given for the murders. She spoke on the issue at various black women’s clubs, and raised more than $500 to investigate lynchings and publish her results.

Wells found that blacks were lynched for such reasons as failing to pay debts, not appearing

to give way to whites, competing with whites economically, and being drunk in public. In 1892. she published her findings in a pamphlet entitled Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. It began with a preface from Frederick Douglass:

to give way to whites, competing with whites economically, and being drunk in public. In 1892. she published her findings in a pamphlet entitled Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. It began with a preface from Frederick Douglass:

Dear Miss Wells:

Let me give you thanks for your faithful paper on the lynch abomination now generally practiced against colored people in the South. There has been no word equal to it in convincing power. I have spoken, but my word is feeble in comparison. You give us what you know and testify from actual knowledge. You have dealt with the facts with cool, painstaking fidelity and left those naked and uncontradicted facts to speak for themselves.

Brave woman! you have done your people and mine a service which can neither be weighed nor measured. If American conscience were only half alive, if the American church and clergy were only half christianized, if American moral sensibility were not hardened by persistent infliction of outrage and crime against colored people, a scream of horror, shame and indignation would rise to Heaven wherever your pamphlet shall be read.

But alas! even crime has power to reproduce itself and create conditions favorable to its own existence. It sometimes seems we are deserted by earth and Heaven yet we must still think, speak and work, and trust in the power of a merciful God for final deliverance.

Frederick Douglass

Very truly and gratefully yours,

FREDERICK DOUGLASSCedar Hill, Anacostia, D.C.,

Oct. 25, 1892

Wells-Barnett later listed fourteen pages of statistics for lynchings from 1892 to 1895, and included pages of graphic stories detailing lynchings in the South. While she was away in Philadelphia, a mob destroyed the offices of her newspaper in Memphis, Free Speech and Headlight, in retaliation for her controversial articles. Because of the threats to her life, she moved from Memphis to Chicago. Wells continued to wage her anti-lynching campaign and to write about Southern injustices. Despite Wells-Barnett's attempt to garner support among white Americans against lynching, she felt her campaign could not overturn the economic interests whites had in using lynching as an instrument to maintain Southern order and discourage prosperity for blacks. Wells-Barnett concluded that reason and compassion for the plight of the Negro would never appeal to Southern whites.

|

| "The Waco Horror" The Crisis, July 1916 |

|

| The crowd at Waco |

Members of the mob castrated Washington, cut off his fingers, and hung him over a bonfire.

He was repeatedly lowered and raised over the fire for about two hours. After the fire was extinguished, his charred torso was dragged through the town and parts of his body were sold as souvenirs. A professional photographer took pictures as the event unfolded, providing rare imagery of a lynching in progress. The pictures were printed and sold as postcards in Waco.

He was repeatedly lowered and raised over the fire for about two hours. After the fire was extinguished, his charred torso was dragged through the town and parts of his body were sold as souvenirs. A professional photographer took pictures as the event unfolded, providing rare imagery of a lynching in progress. The pictures were printed and sold as postcards in Waco.

Although the lynching was supported by many Waco residents, it was condemned by newspapers around the United States. The NAACP hired Elisabeth Freeman to

investigate; she conducted a detailed probe in Waco, despite the reluctance of many residents to speak about the event. NAACP co-founder and editor W.E.B. Du Bois published an in-depth report in The Crisis, featuring photographs of Washington's charred body. Historians have said that Washington's death helped alter the way that lynching was viewed: the publicity it received caused the practice to be seen as barbarism rather than as an acceptable form of justice.

|

| Elisabeth Freeman |

A lynch mob assembled in Waco that night to search the local jail, but dispersed after they did not find Washington. A local newspaper praised their effort. On May 11, a grand jury was assembled in McLennan County and quickly returned an indictment against Washington; the trial was scheduled for May 15. Fleming traveled to Robinson on May 13 to ask residents to remain calm.

|

| McClennan County Courthouse, Waco, Texas |

Court officers approached Washington to escort him away, but were pushed aside by a surge of spectators, who seized Washington and dragged him outside. Washington initially fought back, biting one man, but was soon beaten. A chain was placed around his neck and he was dragged toward city hall by the mob; on the way downtown, he was stripped, stabbed, and repeatedly beaten with blunt objects. By the time he arrived at city hall, a group had prepared wood for a bonfire next to a tree in front of the building. Washington, semiconscious and covered in blood, was doused with oil, hung from the tree by a chain, and then lowered to the ground. Members of the crowd cut off his fingers, toes, and genitals. The fire was lit and Washington was repeatedly raised and lowered into the flames until he burned to death. Washington attempted to climb the chain, but was unable to, owing to his lack of fingers.

The lynching drew a large crowd, including the mayor and the chief of police, although lynching was illegal in Texas. Sheriff Fleming told his deputies not to stop the lynching, and no one was arrested after the event. The crowd numbered 15,000 at its peak. Telephones helped spread word of the lynching, allowing spectators to gather more quickly. Local media reported that "shouts of delight" were heard as Washington burned.

|

| Fred Gildersleeve |

some featuring images of young people gathered around Washington's body: the individuals in the photographs made no attempts to hide their identities. As Waco residents sent the postcard to out-of-town friends and relatives, several prominent local citizens persuaded Gildersleeve to stop selling them, fearing that the images would come to characterize the town.

Within a week, news of the lynching was published as far away as London, England. A New York Times editorial said that "in no other land even pretending to be civilized could a man be burned to death in the streets of a considerable city amid the savage exultation of its inhabitants." Many southern newspapers had previously defended lynching as a defense of civilized society. In Waco, The Waco Morning News briefly noted their disapproval of the lynching, focusing their criticism on newspapers they felt had attacked their city unfairly. They described the condemnatory editorials in the aftermath of the lynching as "Holier than thou" remarks. A writer for the Waco Semi-Weekly Tribune defended the lynching, stating that Washington deserved to die and that blacks should view Washington's death as a warning against crime.

Some Waco residents condemned the lynching, including local ministers and leaders of Baylor University. The judge who presided over Washington's trial later stated that members of the lynch mob were "murderers." A few citizens contemplated staging a protest against the lynching, but decided not to because of threats of violent reprisals.

After the lynching, town officials maintained that it was attended by a small group of malcontents; although their claim was contradicted by the photographic evidence, several histories of Waco have repeated this assertion. There were no negative repercussions for Dollins or Police Chief John McNamara: although they made no attempt to stop the mob, they remained well respected in Waco.

|

| W.E.B. Du Bois |

Any talk of the triumph of Christianity, or the spread of human culture, is idle twaddle as long as the Waco lynching is possible in the United States.After receiving Freeman's report, Du Bois placed an image of Washington's charred body on the cover of the July 1916 issue of The Crisis. The issue was titled "The Waco Horror" and was published as an eight-page supplement. In 1916, The Crisis had a circulation of about 30,000, three times the size of the NAACP's membership. Although the paper had campaigned against lynching in the past, this issue was the first that contained photographs of an attack. The NAACP's board was initially hesitant to publish such graphic content, but Du Bois insisted on doing so, arguing that uncensored coverage would push white Americans to support change. In addition to the images, the issue included accounts of the lynching that Elisabeth Freeman obtained from Waco residents. The article concluded with a call to support the anti-lynching movement.

The NAACP distributed the report to hundreds of newspapers and politicians, a campaign that led to wide condemnation of the lynching. Many white observers were disturbed by the southerners who celebrated the lynching. Oswald Garrison Villard wrote in a later edition of the paper that "the crime at Waco is a challenge to our American civilization." Other black newspapers also carried significant coverage of the lynching, as did liberal papers such as The New Republic and The Nation. Leaders of the NAACP hoped to launch a legal battle against those responsible for Washington's death, but abandoned the plan owing to the projected cost. Elisabeth Freeman traveled around the U.S. to speak to audiences about her investigation, maintaining that a shift in public opinion could accomplish more than legislative actions.

The number of lynchings in the U.S. increased in the late 1910s. Additional lynchings occurred in Waco, partially owing to the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.

|

| Ku Klux Klan March in Washington, D.C. |

After moving to New York, Madam Walker decided to have a national convention for all Walker agents and hair culturists to learn methods for both hair care and business. In 1916 she started organizing the New York area agents as the first chapter of the Madam C.J. Walker Benevolent Association to increase sales and contribute to charitable causes. Walker wanted to organize her agents into clubs that would promote corporate responsibility, social betterment and racial justice. She proposed annual prizes for state organizations with the highest sales and the most generous philanthropy. She continued to travel extensively around the country, speaking at churches, colleges, and conferences. Ransom put advertisements in local black newspapers before her visits. She stressed financial independence, but her message also shifted from a focus on "hair work" to community involvement. She wrote to Ransom about fliers for her company:

In those circulars I wish you would use the words "our" and "we" instead of "I" and "my" . . . Address them as "Dear Friend."

In a trip through the South in October 1916 she visited Louisiana, mentioning in a letter to Ransom that

Went to my home in Delta yesterday and came back to Vicksburg and gave a lecture at Bethel Church to a very appreciative audience.Her visit was reported in a white Louisiana newspaper article titled "World's Richest Negress in Delta,"

Delta was honored Sunday by a visit of the richest negro woman in the world, C.J. Walker, proprietress of a hair straightener remedy. She was born Winnie Breedlove, a daughter of Owen Breedlove, a slave owned by Mr. Robert Burney. She came here to see the place of her nativity, and to call on Mrs. George M. Long, the only daughter of Mr. Burney living here. Mrs. Long has a childhood recollection of Owen Breedlove being one of the "lead hands" of her father. The visitor was very quiet and unassuming and a fine example to her race.

Her travelling, full schedule and hard work took its toll on her health; doctors were so concerned about her blood pressure that they insisted the take a rest. She wrote to Ransom:

I think instead of coming home I will go to Hot Springs where I can really get rest and quietude.

Hot Springs, Arkansas

She went to the Pythian Hotel and Bath House in Hot Springs, Arkansas, a spa and hospital owned by the black Knights of Pythias. W. T. Bailey, head of the architecture department of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, designed the building. The hotel had opened in 1914; the bathhouse provided bathing services half price for members of the Knights of Pythias insurance organization. At the time, Walker was suffering from fatigue and hypertension; doctors believed that the heated baths would lower her blood pressure. She wrote to Ransom:

Madam Walker continued her travelling throughout the south, visiting New Orleans, Baton Rouge, San Antonio, Houston, and many other cities and towns, then going to Tennessee, Kentucky, Indiana, North and South Carolina before returning to New York City in June 1917. It was a productive trip; Ransom wrote her that

I promise you I am going to let all business alone and look strictly after my health except little things which I am going to write to you about now. Ha. HaMadam Walker spent the Christmas holidays in Hot Springs and was joined by Lelia in early January. They agreed to add southern Florida and Cuba to Lelia sales territory, and in March 1917, Lelia took a business trip to Havana, and wrote that it was "the most picturesque place on earth, I do believe."

Madam Walker continued her travelling throughout the south, visiting New Orleans, Baton Rouge, San Antonio, Houston, and many other cities and towns, then going to Tennessee, Kentucky, Indiana, North and South Carolina before returning to New York City in June 1917. It was a productive trip; Ransom wrote her that

At the rate you are now going, we have now but five years before you will be rated as a millionaire, and I feel that every energy ought to be bent in that direction.Annie Turnbo-Malone's company was growing and thriving, but she continued to resent Madam Walker's defection. She criticized the Walker System in print; Madam Walker, regardless of her private feelings, said publicly in a newspaper interview that she hoped for

the banishment of the unpleasant feeling, that the past be forgotten whatever it held and that friendship should exist . . . We are succeeding and that should be sufficient.

|

| Wilson addressing Congress, April 2, 1917 |

In May, Ell Persons, an African American man in Memphis, Tennessee, was lynched on May 22, 1917 after he was accused of having raped and murdered a 16-year-old white girl, Antoinette Rappel. He was arrested and was awaiting trial when he was seized by a lynch mob who burned him alive and scattered his remains around the city of Memphis.

Antoinette Rappel had been found dead, with evidence she had been raped, in woods half a mile from the home of Persons, a fifty year-old woodcutter. She had been decapitated with an axe. At the scene, they found a white coat and a white handkerchief. After the arrests of several black men, the police brought in Persons, and subjected him to brutal treatment for 24 hours: the police said he confessed to the murder.

Eager to prove Persons' guilt, Mike Tate, the Shelby County sheriff, ordered that Rappel's body be exhumed so that they could look at her pupils, because the authorities thought that a photograph of the pupils could be used to show the last image seen by a person who had died. Despite being told by eye specialists that it would be impossible, the authorities said they saw Persons in Rappel's pupils—which showed a "frozen expression of horror"—and he was taken to Tennessee State Prison in Nashville to await arraignment and trial. Judges from the county criminal court tried but failed to persuade the state to send men to protect Persons, as the southern newspapers had been predicting that unofficial action would be taken against him. There is no evidence that the authorities tried to prevent the lynching.

|

| David J. Mays |

The mob chained Persons , poured gasoline over him, and set him afire. David Mays said he stood close to his head "in spite of the African odor" and watched the whole performance. While Persons was burning, spectators snatched pieces of his clothes for souvenirs. Later, Persons' body was decapitated and dismembered, and his remains were scattered and displayed across Beale Street in the African American community in Memphis. His head was thrown from a car at a group of African Americans. Photographs of his burned head were sold on postcards for months after the event. The Commercial Appeal's headline the day after the lynching read: "Thousands cheered when negro burned: Eli Persons pays death penalty for killing girl", and the newspaper's editorial on May 25 described the lynching as "orderly.

No one was charged for the crime. James Weldon Johnson, field secretary of the NAACP,

investigated the case shortly after the lynching, and said there was no evidence Persons was guilty. Standing on the spot where Persons died, he reflected:

East St. Louis was an industrial city on the east bank of the river. Seeking better work and living opportunities, as well as an escape from harsh conditions, many African Americans left the South and moved to industrial centers in the northern and Midwestern United States. In early 1917, blacks were arriving in St. Louis at the rate of 2,000 per week. When industries became embroiled in labor strikes, traditionally white unions sought to strengthen their bargaining position by hindering or excluding black workers, while industry owners utilizing blacks as replacements or strikebreakers added to the divisions. Tensions between the groups escalated, including rumors of black men and white women fraternizing at labor meetings. In May, three thousand white men gathered in downtown East St. Louis and began violently attacking blacks. With mobs destroying buildings and beating people, the Illinois governor called in the National Guard.

|

| James Weldon Johnson |

I tried to balance the sufferings of the miserable victim against the moral degradation of Memphis, and the truth flashed over me that in large measure the race question involves the saving of black America's body and white America's soul.Shortly after the lynching of Ell Persons, a white mob murdered blacks in East St. Louis, Illinois, across the Mississippi River from the city where Madam Walker had lived for more than 16 years. The East St. Louis riots in May and July 1917 were outbreaks of labor- and race-related violence that caused injuries, deaths and extensive property damage.

East St. Louis was an industrial city on the east bank of the river. Seeking better work and living opportunities, as well as an escape from harsh conditions, many African Americans left the South and moved to industrial centers in the northern and Midwestern United States. In early 1917, blacks were arriving in St. Louis at the rate of 2,000 per week. When industries became embroiled in labor strikes, traditionally white unions sought to strengthen their bargaining position by hindering or excluding black workers, while industry owners utilizing blacks as replacements or strikebreakers added to the divisions. Tensions between the groups escalated, including rumors of black men and white women fraternizing at labor meetings. In May, three thousand white men gathered in downtown East St. Louis and began violently attacking blacks. With mobs destroying buildings and beating people, the Illinois governor called in the National Guard.

On July 2, a car occupied by white men drove through a black area of the city and fired several shots into a group of blacks. An hour later, an unmarked car containing four white men, including a journalist and two police officers was passing through the same area. Black residents, assuming that the white shooters had returned, fired guns at their car, killing one officer instantly and mortally wounding another. Later that day, thousands of white spectators assembled to view the detectives' bloodstained automobile. Soon, they marched into the black section of town and started rioting. After cutting the water hoses of the fire department, the rioters burned entire sections of the city and shot inhabitants as they escaped the flames. Claiming that "Southern negros deserve[d] a genuine lynching," they lynched several blacks. Guardsmen were called in, but accounts exist that they joined in the rioting rather than stopping it. After the riot, varying estimates of the death toll circulated. The police chief estimated that 100 blacks had been killed. Ida B. Wells reported in The Chicago Defender that 40-150 black people were killed during July in the rioting in East St. Louis. The NAACP estimated deaths at 100-200.

|

| East St. Louis after the riots and fires |

President Woodrow Wilson made no comment about the events. However, former President Theodore Roosevelt, in New York City at a Carnegie Hall rally celebrating the overthrow of the Russian czar, said:

Before we speak of justice for others, it behooves us to do justice within our own household.

|

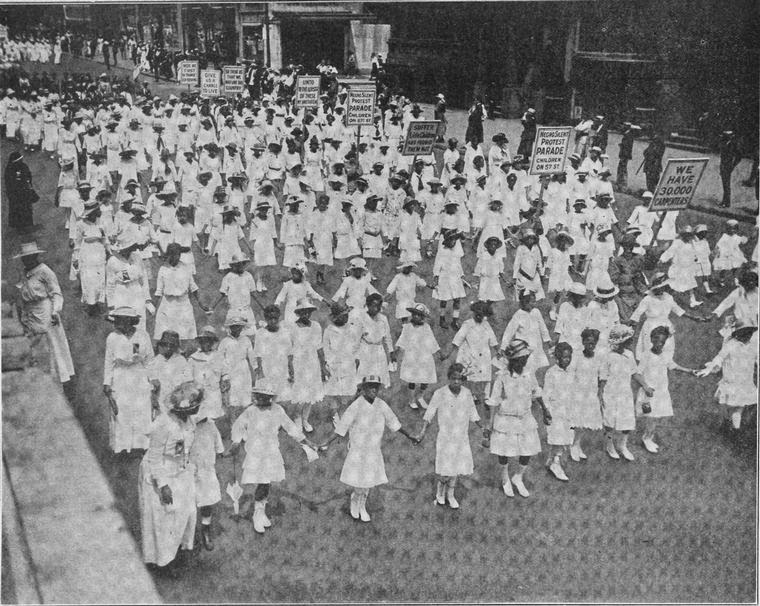

| The Silent Protest, July 28, 1917, New York City |

|

| Girls in the Silent Protest |

We march because we want to make impossible a repetition of Waco, Memphis and East St. Louis, by rousing the conscience of the country and bringing the murderers of our brothers, sisters and innocent children to justice.

Following the Silent Protest, Madam Walker traveled to Washington, D.C. on Wednesday, August 1. She and other African American leaders intended to meet with President Wilson about race relations. Wilson's private secretary, Joseph Tumulty, informed them that Wilson was so busy with an agricultural bill that he would not be able to see them. James Weldon Johnson ridiculed the idea that the bill was more important than murdered citizens; he handed Tumulty a petition that stated that although many thousands of people had participated in criminal lynchings, not even one had been convicted of murder for the death of "2,867 colored men and women" since 1885.

On August 31, 1917, Madam C. J. Walker hosted the first national convention of her Walker “beauty culturists” at Philadelphia’s Union Baptist Church. More than 200 women from all over the United States gathered to learn about sales and marketing. During the convention she gave prizes not only to the women who had sold the most products and brought in the most new sales agents, but also to those who had contributed the most to charity in their communities. She stressed the importance of philanthropy and political engagement. While the focus of the convention was on business opportunities, in her keynote address Madam Walker talked about current events in the nation:

This is the greatest country under the sun. But we must not let our love of country, our patriotic loyalty, cause us to abate one whit in our protest against wrong and injustice. . . . We should protest until the American sense of justice is so aroused that such affairs as the East St. Louis riot be forever impossible.Walker led her convention delegates in sending a telegram to President Woodrow Wilson protesting the lynchings and riots; it read:

“We, the representatives of the National Convention of the Mme. C. J. Walker Agents, in convention assembled, and in a larger sense representing twelve million Negroes, have keenly felt the injustice done our race and country through the recent lynching at Memphis, Tennessee and the horrible race riot at East St. Louis. Knowing that no people in all the world are more loyal and patriotic than the Colored people of America, we respectfully submit to you this our protest against the continuation of such wrongs and injustices in this ‘land of the free and home of the brave’ and we further respectfully urge that you as President of these United States use your great influence that congress enact the necessary laws to prevent a recurrence of such disgraceful affairs.”

form the National Negro Cosmetics Manufacturers Association. According to the minutes:

It has been so often the case that the white man who is not interested in Colored Women's Beauty only looks to further his own gains and puts on the market preparations that are absolutely of no aid whatsoever to the Skin, Scalp, or Hair.

Madam Walker hoped the organization would "encourage the development of Race enterprises and acquaint the public with the superior claims of high class goods." Walker was elected president, with women holding half of the six executive committee positions.

In September, about 200 men and women met at Mother AME Zion Church for the 10th annual convention of Monroe Trotter's National Equal Rights League. Delegates voted to demand that President Wilson abolish segregation in federal office and interstate travel, present disenfranchisement of black voters, and make lynching a federal crime. Their "Address to the American People" stated that "We are still surrounded by an adverse sentiment which makes our lives a living hell."

In September, about 200 men and women met at Mother AME Zion Church for the 10th annual convention of Monroe Trotter's National Equal Rights League. Delegates voted to demand that President Wilson abolish segregation in federal office and interstate travel, present disenfranchisement of black voters, and make lynching a federal crime. Their "Address to the American People" stated that "We are still surrounded by an adverse sentiment which makes our lives a living hell."

Born on American soil, our ancestors here for centuries, we like the rest of you are Americans, and speak as true Americans. Having watered the American soil with our tears, enriched it with our blood, defended it in every war, never disloyal or untrue to its best interests, manifesting now common interest with all true Americans in its welfare, honor and glory, we, in our hour of extremity, appeal to your conscience, sense of justice and .fair play and demand that the many outrages and indignities cease and our race be accorded the same rights and privileges accorded all other Americans.

Despite progress we are still surrounded by an adverse sentiment which makes our lives a living hell.

We are shut out by trades-unions, and refused work. We are rejected in business, in professional service and even by the government as clerks solely because of color. The Senate of the United States has gone so far as to have a jim-crow corner in its gallery.

Neither the Churches of Christ nor the Courts of Law have overcome the color line, in our Southland it has long been the custom, when a Colored man is accused of crime to set aside "the usual process of law and turn him over to the mob to be stabbed, hung, shot or burned at the stake outrages that would not be permitted in any other country on the globe.

. . . The most discouraging feature is that the white pulpit is usually silent and the white press silent, if not siding with the mob. These inhuman outrages have been winked at by those in authority until they are no longer confined to the South, but are spreading through the entire country and are casting a blot upon American Civilization that cannot be effaced. At a time like this when our country is in war to uphold democracy and to prove that our government is the best on earth and as President Wilson said, we should "establish in this country justice with heart in it and sympathy in it," it behooves the American people to make these outrages against humanity impossible.

Not only should the "World be made safe for Democracy," but "Democracy should be made safe for the World."

. . . The National Equal Rights League congratulates the nation upon the fact that the basic principles of the government, human equality and human freedom, have been applied with increasing comprehensiveness to those races which make seven-eights of our population. . . It declares that the increasing

withdrawal of these principles from the other eighth of the population is a challenge of the patriotism of our governmental administrators and of our fellow white Americans.

The entrance, therefore, of the U. S. A. offensively into the most terrible war in history . . .can be justified only by vouchsafing freedom and equality of rights to all citizens of the United States regardless of the incidents of race or color over which they have no control. Likewise all true patriots should lay aside hatred and discrimination against fellow Americans.

Now comes the President of the United States and declares officially to the world that this government takes part in the European war to prom0te World Democracy and World Humanity. He tells the new army raised specifically to make the world "Safe for Democracy," that this war "draws us all closer together in human brotherhood as did the Revolutionary War for American Independence."

Hence, in view of his own words and of this war, we do now call upon President Wilson to abolish that essential violation of democracy, race segregation of government clerks, and to recommend to Congress the enactment of laws: (a) To enforce the 14th and 1 5th Amendments of the Constitution which forbid peonage and disfranchisement, thereby restoring to millions of Americans their civil and political rights; (b) To make lynching a federal crime; (c) To forbid segregation for race m interstate travel, or travel in federal territory.

. . . Colored Americans demand only that the "rights of free peoples and the common rights of mankind" which the government proclaims for Europe be also in the possession at home of all our citizens . . We believe in democracy. . . .

We demand equality of rights for all . . .

|

| Ida B. Wells-Barnett |

We drove out there almost every day, and I asked her on one occasion what on earth she would do with a thirty-room house. She said, "I want plenty of room in which to entertain my friends. I have worked so hard all of my life that I would like to rest."

|

| Villa Lewaro |

I am not a millionaire, but I hope to be some day . . . not because of the money, but because I could do so much more to help my race.

|

| Breathing Exercises at Battle Creek |

In April 1918, Madam Walker went to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania for the Madam C.J. Walker Benevolent Association meeting of 600 people, telling them:

In July, Walker and Mary Burnett Talbert celebrated a mortgage-burning ceremony marking the successful campaign to purchase Cedar Hill, the Washington, D.C. home of Frederick Douglass. The women of NACW had plans to convert the house into a museum and archive dedicated to Douglass. Walker had donated $500, which made her the largest single donor.

Mary Morris Burnett Talbert, born in Oberlin, Ohio in 1866 was the only African-American woman in her graduating class from Oberlin College in 1886. She received a Bachelor of Arts degree and became a teacher. In 1891 she married William H. Talbert and moved to New York. She was one of the founders of the Niagara movement, and later was active in the NAACP. Talbert's long leadership of women's clubs helped to develop black female organizations and leaders in communities around New York and the United States. Talbert led the campaign to save Douglass home in Anacostia, after other efforts had failed.

In August 1918, Walker convened another convention in Chicago; in her keynote address, after being greeted with a standing ovation, she said

When the United States had declared war against Germany in April of 1917, War Department planners realized that the United States' standing army of 126,000 men would not be enough to achieve a victory. The standard volunteer system proved to be inadequate in getting enough recruits, and on May 18, 1917 Congress passed the Selective Service Act requiring all male citizens between the ages of 21 and 31 to register for the draft. Even before the act was passed, African American males from all over the country had joined the war effort: they viewed the conflict as an opportunity to prove their loyalty, patriotism, and worthiness for equal treatment in the United States. When World War I broke out, there were four all-black regiments in the United States Army: the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry. Within one week of Wilson’s declaration of war, the War Department had to stop accepting black volunteers because the quotas for African Americans were filled.

What I have done, you can do . . . I am here to interest and inspire you.She moved into Villa Lewaro in May 1918; from the balcony outside her bedroom she could see the New Jersey Palisades above the Hudson River. Walker told a reporter:

I had a dream and that dream begot other dreams until now I am surrounded by all my dreams come true.

|

| Mary Burnett Talbert |

We are here not only to transact the business of the convention, not only to inspire and receive inspiration, but to pledge anew our loyalty and patriotism . . . and to say to our President that the Colored women of America are ready and willing to make any sacrifice necessary to bring our boys home victorious. . .

I want you to know that whatever I have accomplished in life I have paid for it by much thought and hard work. If there is any easy way, I haven't found it. My advice to every one expecting to go into business is to strike with all your might.

. . . I want my agents to feel that their first duty is to humanity. . . . I tell you that we have a duty to perform with reference to our brother and sister from the South. Shall we who call ourselves Christians sit still and allow them to be swallowed up and lost in the slums of these great cities?

. . . Lend them the encouragement of your friendly interest, that the light of hope may continue to shine in their eyes and worthy ambitions continue to throb in their hearts.On the final day of the conference, the Chicago Defender's headline was the story of two black women who had been tarred and feathered in Vicksburg, Mississippi. One woman was the wife of a soldier in France.

When the United States had declared war against Germany in April of 1917, War Department planners realized that the United States' standing army of 126,000 men would not be enough to achieve a victory. The standard volunteer system proved to be inadequate in getting enough recruits, and on May 18, 1917 Congress passed the Selective Service Act requiring all male citizens between the ages of 21 and 31 to register for the draft. Even before the act was passed, African American males from all over the country had joined the war effort: they viewed the conflict as an opportunity to prove their loyalty, patriotism, and worthiness for equal treatment in the United States. When World War I broke out, there were four all-black regiments in the United States Army: the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry. Within one week of Wilson’s declaration of war, the War Department had to stop accepting black volunteers because the quotas for African Americans were filled.