Clement Laird Vallandigham was born New Lisbon, Ohio (now Lisbon, Ohio), the fifth of seven children of Clement Vallandigham, a Presbyterian minister, and his wife Rebecca Laird Vallandigham.

In 1837, he began studies at his father's alma mater, Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. Because of family finances, he moved to Maryland and for two years was a preceptor at Union Academy in Snow Hill, in order to earn money for his college tuition.

1. Live in habitual communion with God.

2. Cultivate a grateful spirit.

3. Cultivate a cheerful spirit.

4. Cultivate an affectionate spirit.

5. Let not the attainment of happiness be your direct object.

6. Cultivate decision of character.

Moral courage : Independence.

His father died in 1839. In 1840 he returned to Jefferson College, but after a dispute with the Jefferson College president, he was honorably dismissed in 1841. He never received a diploma.

He was 41 years old when the Civil War began.

|

| Ohio |

Vallandigham was elected as a Democrat to the Ohio legislature in 1845 and 1846. While in the Ohio state legislature, Vallandigham voted against the repeal of the "Black Laws" (laws against the civil rights of African-Americans), but wanted the question put to a referendum by the voters.

Vallandigham and Edwin Stanton, the future Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln, were friends before the Civil War. Stanton lent Vallandigham $500 for a course and to begin his law practice. Both Vallandigham and Stanton were Democrats, but had opposing views of slavery.

|

| Edwin Stanton and Son |

Vallandigham moved to Dayton, Ohio in 1847. He applied himself to his law practice, which paid well enough to fund the purchase of a substantial home located at 323 1st Street, a fashionable residential area in Dayton. He bought a half-interest in a weekly newspaper, The Dayton Empire, and was an editor from 1847 until 1849.

Steeped in the writings of English philosopher Edmund Burke, Vallandigham was a conservative who was devoted to stability, order, and tradition. For this reason, he was a bitter critic and opponent of abolitionism. As early as 1850, Vallandigham publicly announced his opposition to slavery; however, since the Constitution granted Southern states the right to maintain the peculiar institution, Vallandigham maintained that abolitionists wanted something that was unjust to the South. In 1855, Vallandigham told a Dayton audience, “Patriotism above mock philanthropy; the Constitution before any miscalled higher laws of morals or religion; and the Union of more value than many negroes.” To Vallandigham, the abolitionists’ appeal to a higher law was unacceptable and potentially destabilizing.

Increasingly, Vallandigham began to place blame on abolitionists and the Republican Party for the nation’s problems as opposed to Southern fire-eaters. Vallandigham was a vigorous supporter of constitutional states' rights. He believed the federal government had no power to regulate a legal institution, which slavery then was. He also believed the states had a right to secede, and that the Confederacy could not constitutionally be conquered militarily.

In October 1859, when John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry failed, Vallandigham traveled to Harpers Ferry on his way home to Ohio to interview the abolitionist. Vallandigham’s intention was to uncover evidence of organized abolitionists’ sponsorship of Brown’s raid. Brown, however, would not take the bait and Vallandigham returned empty-handed, although he earned the abuse of numerous Republican papers that accused him of trying to profit politically from Brown’s raid.

|

| John Brown |

During the 1860 presidential campaign he supported Stephen Douglas. Upon returning to Washington in early December 1860 for the opening of Congress, Vallandigham wrote his wife, “They who some centuries hence shall read the history of these times, will be amazed at the folly and blindness of us who live and act now.” Vallandigham became convinced that congressional Republicans were the real culprits. “Every day proves still more clearly,” he wrote his wife on Christmas Eve, 1860, “that it is the fixed purpose of the Republican party not only to refuse all compromise, but to force a civil war.”

|

| Stephen Douglas |

On the subject of war, he had already publicly expressed his opposition to all forms of coercion. In a speech given at the Cooper’s Institute in New York City, Vallandigham declared, “I never would as a Representative in the Congress of the United States vote one dollar of money whereby one drop of American blood should be shed in a civil war.” To his congressional colleagues, he declared on December 22, 1860, “I am all over and altogether a Union man. I would preserve it in all its integrity and worth. But I repeat that this cannot be done by coercion—by the sword.”

On February 20, 1861, Vallandigham delivered a speech titled "The Great American Revolution" to the House of Representatives. He accused the Republican Party of being "belligerent" and advocated "choice of peaceable disunion upon the one hand, or Union through adjustment and conciliation upon the other." Vallandigham supported Crittenden Compromise. He blamed sectionalism and anti-slavery sentiment for the secession crisis.

When it was obvious that the Crittenden compromise proposals as well as the Washington Peace Conference had failed, Vallandigham introduced his own compromise proposals in the form of three amendments to the Constitution. The first, a proposed Thirteenth Amendment, was a variation on John C. Calhoun’s notion of a concurrent majorities. It divided the nation into four sections: North, South, West, and Pacific. Each section would have an equal number of electors, and the nation’s president and vice president could be elected only if a majority of electors from each section agreed. The proposed Fourteenth Amendment would have allowed for secession if all the states in a section agreed on it. Finally, the proposed Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed equal rights to all citizens in federal territories, including slaveholders—thus granting the Deep South the moral equivalent of a federal slave code. Predictably Republicans in Congress did not seriously consider Vallandigham’s proposals, which died as Congress adjourned in early March just prior to Lincoln’s inauguration.

Vallandigham was skeptical of Lincoln’s inaugural address, arguing that he could not determine whether the president was for war or for peace. However, when the firing on Fort Sumter took place on April 12, he resisted the tide of public opinion that supported war and stuck to the position that he had articulated since the fall of 1860. When Lincoln called upon the states for 75,000 men to put down the rebellion, Vallandigham publicly commented, “I will not vote to sustain or ratify—never! Millions for defense; not a dollar or a man for aggressive and offensive civil war.”

Vallandigham was skeptical of Lincoln’s inaugural address, arguing that he could not determine whether the president was for war or for peace. However, when the firing on Fort Sumter took place on April 12, he resisted the tide of public opinion that supported war and stuck to the position that he had articulated since the fall of 1860. When Lincoln called upon the states for 75,000 men to put down the rebellion, Vallandigham publicly commented, “I will not vote to sustain or ratify—never! Millions for defense; not a dollar or a man for aggressive and offensive civil war.”

He published a letter in the April 20, 1861 Cincinnati Daily Enquirer stating his belief that the South could not be coerced into reentering the Union. Supported by vocal immigrant and farm constituencies in Ohio, he blamed the war on Lincoln and the Republican Party, voted against national Conscription, refused to cooperate with congressional war measures, and alienated the powers within his own political party. He strongly opposed every military bill, leading his opponents to charge that he wanted the Confederacy to win the war.

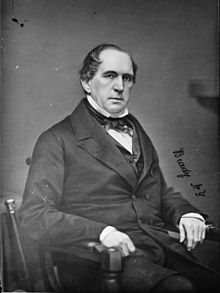

|

| Clement Vallandigham |

Denouncing many of President Lincoln’s actions during May and June—suspending the writ of habeas corpus and increasing the size of the regular army, for instance—as unconstitutional, Vallandigham introduced a number of resolutions criticizing the president for unconstitutional actions. Both Republicans and Democrats joined to table the resolutions. Undaunted, Vallandigham persisted in his criticism of the war. “I am for peace, speedy, immediate, honorable PEACE, with all its blessings,” he told the House of Representatives.During the meeting of the special session of Congress in July 1861, Vallandigham stood almost alone in his opposition to the war.

During the first regular session of the Thirty-seventh Congress, Vallandigham continued his opposition to the war. During the winter of 1861–1862, dissatisfaction with Republican policy toward slavery began to slowly erode Democratic support for the war. Beginning with the repeal of the Crittenden-Johnson resolution in December 1861, Lincoln and the Republican Congress began chipping away at the peculiar institution with such proposals as abolishing slavery in Washington, D.C.; forbidding army officers to return fugitive slaves to masters; and finally the president’s own proposal for compensated emancipation in the border states.

Sensing an opportunity, in the spring of 1862, Vallandigham organized a group of congressional Democrats that formulated “An Address of the Democratic Members of Congress to the Democracy of the United States.” Urging conciliation and compromise toward the South, the document emphasized respect for civil liberties and states’ rights, and criticized what were perceived as the revolutionary excesses of the Lincoln administration. While hardly representing the majority of Democrats in Congress, the address was, at least, an indication that Vallandigham was no longer a “voice in the wilderness” with respect to his position on the war.

Vallandigham’s Republican colleagues in Congress frequently accused him of disloyalty. Vallandigham did not take such accusations lightly. When radical Republican Senator Benjamin F. Wade denounced Vallandigham as a traitor in a speech in Washington, D.C., the Ohio congressman used the House of Representatives to reply to his Republican antagonist. Gaining the floor on April 24, 1862, Vallandigham read a portion of Wade’s speech to the House. He then uttered the following words: “Now, Sir, here in my place in the House, as a Representative I denounce . . . the author of that speech as a liar, a scoundrel, and a coward. His name is BENJAMIN F. WADE.” House Republicans objected and eventually tried to censure Vallandigham for his remarks, an attempt that proved unsuccessful.

"To maintain the Constitution as it is, and to restore the Union as it was."

It was endorsed by fifteen Democratic congressmen.

|

| Clement Vallandigham, seated first on left, with Copperhead Congressmen |

But he was abandoned by the state's War Democrats in a fight to keep his original congressional district intact. It was gerrymandered to contain a minority of his supporters, and he was not reelected to a third term in 1862.

Vallandigham gave a speech titled "The Constitution-Peace-Reunion", delivered in the House of Representatives on January 14, 1863:

Soon after the war began the reign of the mob was… supplanted by the iron domination of arbitrary power. Constitutional limitation was broken down; habeas corpus fell; liberty of the press, of speech, of the person, of the mails, of travel, of one’s own house, and of religion; the right to bear arms, due process of law, judicial trial, trial by jury, trial at all; every badge and monument of freedom in republican government or kingly government–all went down at a blow; and the chief law-officer of the crown–I beg pardon, sir, but it is easy now to fall into this courtly language–the Attorney-General, first of all men, proclaimed in the United States the maxim of Roman servility: Whatever pleases the President, that is law! Prisoners of state were then first heard of here. Midnight and arbitrary arrests commenced; travel was interdicted; trade embargoed; passports demanded; bastiles were introduced; strange oaths invented; a secret police organized; “piping” began; informers multiplied; spies now first appeared in America. The right to declare war, to raise and support armies, and to provide and maintain a navy, was usurped by the Executive….

And now, sir, I recur to the state of the Union to-day. What is it? Sir, twenty months have elapsed, but the rebellion is not crushed out; its military power has not been broken; the insurgents have not dispersed. The Union is not restored; nor the Constitution maintained; nor the laws enforced. Twenty, sixty, ninety, three hundred, six hundred days have passed; a thousand millions been expended; and three hundred thousand lives lost or bodies mangled; and to-day the Confederate flag is still near the Potomac and the Ohio, and the Confederate Government stronger, many times, than at the beginning….

Thus, with twenty millions of people, and every element of strength and force at command–power, patronage, influence, unanimity, enthusiasm, confidence, credit, money, men, an Army and a Navy the largest and the noblest ever set in the field, or afloat upon the sea; with the support, almost servile, of every State, county, and municipality in the North and West, with a Congress swift to do the bidding of the Executive; without opposition anywhere at home; and with an arbitrary power which neither the Czar of Russia, nor the Emperor of Austria dare exercise; yet after nearly two years of more vigorous prosecution of war than ever recorded in history;… you have utterly, signally, disastrously–I will not say ignominiously–failed to subdue ten millions of “rebels,” whom you had taught the people of the North and West not only to hate, but to despise….

You have not conquered the South. You never will. It is not in the nature of things possible; much less under your auspices. But money you have expended without limit, and blood poured out like water. Defeat, debt, taxation, sepulchres, these are your trophies….

Slavery is the cause of the war. Why? Because the South obstinately and wickedly refused to restrict or abolish it at the demand of the philosophers or fanatics and demagogues of the North and West. . . . It was abolition, the purpose to abolish or interfere with and hem in slavery, which caused disunion and war. Slavery is only the subject, but Abolition the cause of this civil war. It was the persistent and determined agitation in the free States of the question of abolishing slavery in the South…

I see more of barbarism and sin, a thousand times, in the continuance of this war, the dissolution of the Union, the breaking up of this Government, and the enslavement of the white race, by debt and taxes and arbitrary power.

I accept the language and intent of the Indiana resolution, to the full–”that in considering terms of settlement, we will look only to the welfare, peace, and safety of the white race, without reference to the effect that settlement may have upon the condition of the African.”

...The people begin, at last, to comprehend, that domestic slavery in the South is a question; not of morals, or religion, or humanity, but a form of labor, perfectly compatible with the dignity of free white labor in the same community, and with national vigor, power, and prosperity, and especially with military strength….Predictably Vallandigham’s speech generated a good deal of attention in the press. Vallandigham returned to Dayton as a private citizen. His return was marked by a Democratic rally, where the former congressman delivered a scathing rebuke of the Lincoln administration. Concerned that Republican power was a threat to constitutional liberties, Vallandigham spoke frequently in Ohio and other parts of the country. The tone of his speeches became increasingly critical of administration policy on civil rights and free speech.

|

| Ambrose Burnside |

On April 13, 1863, General Ambrose Burnside, who commanded the Department of Ohio, issued General Order Number 38, warning that the "habit of declaring sympathies for the enemy" would not be tolerated in the Military District of Ohio:

That hereafter all persons found within our lines who commit acts for the benefit of the enemies of our country, will be tried as spies or traitors, and, if convicted, will suffer death. . . . Persons committing such offences will be at once arrested, with a view to being tried as above stated, or sent beyond our lines into the lines of their friends.

Vallandigham gave a speech at Mount Vernon, Ohio, on May 1, 1863, charging that the war was being fought not to save the Union but to free the slaves by sacrificing the liberty of all Americans to "King Lincoln". Peace Democrats Vallandigham, Samuel Cox, and George Pendleton all delivered speeches denouncing General Order No. 38. Vallandigham was so opposed to the order that he allegedly said that he "despised it, spit upon it, trampled it under his feet."

On May 5, 1863, Vallandigham was arrested at his home at 2 a.m. as a violator of General Order Number 38. When Vallandigham refused to grant the soldiers admission, they forcibly broke down the door. The soldiers pursued a retreating Vallandigham into his home as his frightened wife screamed. Hoping to attract attention to his plight, Vallandigham fired a gun out the window. Eventually pinned in an interior room with no escape, he eventually surrendered with the words, “You have now broken open my house and over powered me by superior force, and I am obliged to surrender.”

|

| Illustration, Arrest of Clement Vallandigham |

His enraged supporters burned the offices of the Dayton Journal, the Republican rival to the Dayton Empire.

Vallandigham was tried by a military court on May 6 and 7; his speech on May 1 was cited as the source of the arrest. He was charged by the Military Commission with "Publicly expressing, in violation of General Orders No. 38, from Head-quarters Department of the Ohio, sympathy for those in arms against the Government of the United States, and declaring disloyal sentiments and opinions, with the object and purpose of weakening the power of the Government in its efforts to suppress an unlawful rebellion." He was sentenced to confinement in a military prison "during the continuance of the war" at Fort Warren in Boston, Massachusetts.

On May 11, 1863, an application for a writ of habeas corpus was filed in federal court for Vallandigham by former Ohio Senator George Pugh. Judge Humphrey Leavitt of the Circuit Court of the United States for the Southern District of Ohio upheld Vallandigham's

arrest and military trial as a valid exercise of the President's war powers.

|

| Horatio Seymour |

Controversy and protests ensued. On May 16, 1863, there was a meeting at Albany, New York to protest the arrest of Vallandigham. A letter from Governor Horatio Seymour of New York was read to the crowd. Seymour charged that "military despotism" had been established. Resolutions by John Pruyin were adopted, and sent to President Lincoln by Erastus Corning.

|

| Erastus Corning |

Lincoln, who considered Vallandigham a "wily agitator", was wary of making him a martyr to the Copperhead cause. Following a May 19 cabinet meeting, Lincoln commuted Vallandigham's sentence to banishment to the Confederacy. On May 26, he was taken to Confederates south of Murfreesboro, Tennessee. When he was within Confederate lines, Vallandigham said: "I am a citizen of Ohio, and of the United States. I am here within your lines by force, and against my will. I therefore surrender myself to you as a prisoner of war."

Once Vallandigham was in the custody of Confederate General Braxton Bragg, the Confederate government had a dilemma. He had not come willingly across lines, nor was he in sympathy with the rebellion. In fact, Vallandigham’s position was based on reunion through peace, not recognition of the Confederacy. The premise of the Confederacy was to deny reunion and assert independence as a sine qua non. In consultation with Richmond, Bragg was directed to send the prisoner to Lynchburg, Virginia. There the Davis administration directed General Robert Ould, commissioner of prisoner exchanges, to interview the prisoner.

On May 30, 1863, there was a meeting at Military Park in Newark, New Jersey, where a letter from New Jersey Governor Joel Parker was read. His letter condemned the arrest, trial and deportation of Vallandigham, saying they "were arbitrary and illegal acts. The whole proceeding was wrong in principle and dangerous in its tendency." On June 1, 1863, there was a protest meeting in Philadelphia.

Democrats in Ohio, angry at the treatment of Vallandigham, gave him the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in absentia at their June 11 convention. The candidate for lieutenant governor, George Pugh, represented Vallandigham's views at rallies and in the press.

|

| George Pugh |

In response to the public letter issued at the meeting of Democrats in Albany, Lincoln's Letter to Erastus Corning, et al" of June 12, 1863, explains his justification for supporting the court-martial's conviction.

|

| A RARE OLD GAME OF "SHUTTLECOCK." JEFF - "No use sending him here. I'll have to send him back" ABE - He's none of mine anyhow."Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper June 20, 1863 |

|

| Cartoon about the Vallandigham Guberatorial Campaign |

While in Canada, Vallandigham met with Jacob Thompson, a representative of the Confederate government. They talked about plans for forming a Northwestern Confederacy, consisting of the states of Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois, by overthrowing their governments. He requested money for weapons from the Confederates. Vallandigham refused to handle the money himself and it was given to his associate, James Barrett.

|

| Jacob Thompson |

Lincoln interested himself in the election, endorsed Republican candidate John Brough, and claimed that a vote for the Democratic contender was "a discredit to the country." President Lincoln wrote the Birchard Letter of June 29, 1863, to several Ohio congressmen, offering to revoke Vallandigham's deportation order if they would agree to support certain policies of the Administration.

Vallandigham asked the question in his letter of July 15, 1863, "To the Democracy of Ohio":

"Shall there be free speech, a free press, peaceable assemblages of the people, and a free ballot any longer in Ohio?"

Unfortunately for Vallandigham, Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg stemmed the high tide of the antiwar feeling in the North. In the election on October 13, 1863, John Brough defeated Vallandigham with votes of 288,374 to 187,492. While he accepted defeat, Vallandigham believed he had won a more important battle. “You were beaten,” he told Ohio Democrats, “but a nobler battle for constitutional liberty and free popular government never was fought by any people.”

Vallandigham's deportation to the Confederacy prompted Edward Everett Hale to write The Man Without a Country, which appeared in The Atlantic Monthly in December 1863.

|

| The Man Without a Country |

Rumors circulated throughout the Union during 1864 that Confederate sympathizers intended to free Confederate prisoners at several prison camps, including Johnson's Island and Camp Chase, in Ohio. These freed prisoners would form the basis of a new Confederate army that would operate in the heart of the Union. Supposedly, General John Hunt Morgan, who had raided Ohio the previous year, would return to the state and assist this new army.

The plot never materialized. General William Rosecrans, assigned to oversee the Department of Missouri, discovered the planned uprising and warned Union governors to remain cautious. John Brough, Ohio's governor, sent out spies to infiltrate the groups of sympathizers. These men succeeded and stopped the uprising before it could occur. Confederate supporters hoped to capture the Michigan, a gunboat operating on Lake Erie near Sandusky. They would then use the gunboat to free Confederate prisoners at Johnson Island. Union authorities arrested the plot's ringleader, Charles Cole.

Vallandigham returned to the United States "under heavy disguise" and publicly appeared at an Ohio convention on June 15, 1864. President Lincoln was informed of his return. On June 24, 1864, Lincoln drafted a letter to Governor Brough and General Heintzelman stating "watch Vallandigham and others closely" and arrest them if needed. However, he did not send the letter and it appears he decided to do nothing about Vallandigham's return.

Vallandigham's mother died on July 8, 1864.

|

| Grave of Reverend Clement & Rebecca Laird Vallandigham |

In late August 1864, Vallandigham openly attended the Democratic National Convention in Chicago as a District Delegate for Ohio. The reception by the convention to Vallandigham was mixed. At one point Vallandigham's name was called out by the audience and the response was "applause and hisses". There were "cheers and hisses" on another occasion when he spoke. Vallandigham promoted the "peace plank" of the platform, declaring the war a failure and demanding an immediate end of hostilities.

|

| Cartoon, "HowColumbia Receives McClellan's Salutation from the Chicago Platform" |

In his acceptance letter for the Democratic Presidential nomination, George McClellan made peace conditional on the Confederacy being ready for peace and ready to rejoin the Union.McClellan's stance conflicted with the Democratic Party Platform of 1864 which stated that "immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of the States, or other peaceable means, to the end that, at the earliest practicable moment".

Vallandigham supported his party's nomination of McClellan for the presidency but was "highly indignant" when McClellan repudiated the party platform in his letter of acceptance of the nomination. For a time, Vallandigham withdrew from campaigning for McClellan. Vallandigham was included on the Democratic ticket as Secretary of War.

|

| Election Poster Against McClellan, Pendleton and Vallandigham |

While Democrats had gone into the fall campaign confident that Lincoln would not be reelected, a number of actions and events quickly tempered Democratic optimism. The Democrats’ own action at the Chicago convention was significant. Republicans ridiculed the party as featuring a war candidate on a peace platform—a strategy that paid dividends.

Equally important were changing military fortunes. During the summer of 1864, Grant’s high casualties in Virginia and the failure of Sherman to deliver a knockout punch in Georgia contributed to war weariness. By the fall, however, the situation had changed. Sherman had taken Atlanta, David Farragut had taken Mobile Bay, while Grant was increasing his pressure on Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in the trenches near Petersburg, Virginia.

|

| 1864 Cartoon Lampooning the Copperheads and Peace Democrats |

Finally, provisions for the voting of soldiers was guaranteed to give the Republican ticket a decided advantage. With Lincoln’s reelection in November 1864, Vallandigham’s hope of peaceful reunion was crushed, as was his hope for a return to the republic of antebellum times.

After the war ended, the Democratic party declared him persona non grata at its 1866 Philadelphia convention, a meeting of old Federals and recently reconstructed Southern Democrats, where it was felt his presence was disruptive. In 1867, he lost his campaigns for the Ohio State Senate against Judge Allen Thurman and the House of Representatives against Robert Schenck on an anti-Reconstruction platform. Vallandigham continued his stance against African-American suffrage and equality.

|

| The Golden Lamb |

At 9 p.m. he sent a telegram to his doctor: “Dr. Reeve—I shot myself by accident with a pistol in the bowels. I fear I am fatally injured. Come at once."

He died the next morning, Saturday, June 17, 1871. He was 50 years old.

Vallandigham proved his point, and the defendant, Thomas McGehan, was acquitted and released from custody. (He was murdered four years later in 1875).

|

| Vallandigham Grave |

In 1872, his older brother, Reverend James Vallandigham, published a biography, A Life of Clement Vallandigham.

|

| Photograph from A Life of Clement Vallandigham |

According to employees, Vallandigham’s ghost is a regular at The Golden Lamb. A manager at the inn said that his profile once appeared in a window in a photo taken upstairs. A server reported seeing a man dressed in old-fashioned clothes and wearing a “tall hat”—possibly an 1860s style stovepipe hat—in a dining room on the second floor, and a housekeeper said she saw a man matching that description sitting on a bench in the hall on the fourth floor. Both descriptions of the man strongly resemble Vallandigham.

|

| Golden Lamb Room where Vallandigham died |

Some people claim, however, that the male ghost may be that of Ohio Supreme Court Justice Charles R. Sherman, the father of Civil War General William T. Sherman. Justice Sherman died suddenly at the inn at the age of forty-one, leaving his wife and eleven children penniless.

This is a great entry, Who are you?

ReplyDeleteDoes anyone read this any more?