Greenhow wept in the Senate Gallery on January 21, 1861, when her friend Jefferson Davis said farewell to the Senate and went off to lead the Confederacy.

In March of 1861, Greenhow's daughter Gertrude, 23, died after a long illness of typhoid fever. Leila, 21, and Little Rose, 8, remained with her.

Greenhow had grown cool to her niece since Addie's marriage to Stephen Douglas, and the Douglases' support of Lincoln was especially irritating. Addie's brother, James Madison Cutts, Jr., joined the First Rhode Island Volunteers.

Greenhow's son-in-law, Seymour Moore, was serving in Utah as a Captain in the Quartermaster Corps at the outbreak of the Civil War. He first joined the staff of Brigadier General James H. Carleton's staff as his Assistant Quartermaster, then served as the Chief Quartermaster of the Wheeling, West Virginia depot. Although he was fond of his mother-in-law, he did not hide his strong support for the Union. Florence wrote to her mother that Moore "believes that all Southerners should be hanged."

|

| Thomas Jordan |

As early as 1860, Captain Thomas Jordan, of the Union Army, a classmate of William Sherman at West Point, secretly began a pro-Southern spy network in Washington, D.C. In early 1861, Jordan passed control of the espionage network to Greenhow when he resigned from the U.S. Army and was commissioned as a captain in the Confederate army. Jordan supplied Greenhow with a 26-symbol cipher for encoding messages. By June 1861, Jordan had become a lieutenant colonel and a staff officer under P.G.T. Beauregard.

|

| P.G.T. Beauregard |

Greenhow overheard and collected war secrets from her friends and acquaintances. Her admirers included Senator Henry Wilson, then chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs, and Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon. On July 9 and July 16 of 1861, Greenhow passed secret messages to General Beauregard containing information regarding Union military movements for what would be the First Battle of Bull run, including the plans of General Irvin McDowell.

|

| Irvin McDowell |

Assisting in her conspiracy were pro-Confederate members of Congress, Union officers, and her dentist, Aaron Van Camp, and his son and Confederate soldier, Eugene B. Van Camp. A 16-year-old Maryland girl named Betty Duvall carried Greenhow's messages, wrapped in a tiny black silk purse and wound up in a chignon of Duvall's hair.

|

| Betty Duvall |

Greenhow was not in Washington when word was first received of the intense fighting on July 21. She had taken her daughter Leila to New York for the first leg of her journey to join the Moores in Utah. At first she heard in New York that the North was winning, but by the time she reached Washington, D.C. on July 23 at six o'clock in the morning, the city was in chaos.

|

| Illustration of Battle of Bull Run |

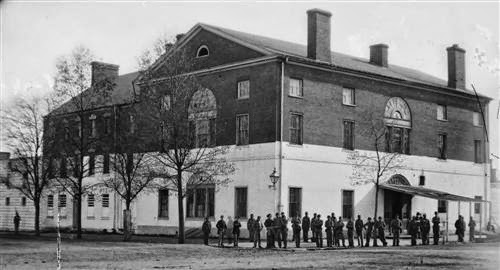

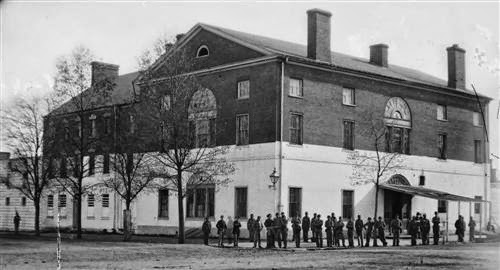

Immediately after the First Battle of Bull Run/Manassas, Confederate prisoners were marched through the streets to the Old Capitol Building on First Street—the building where Greenhow had lived when it was a boarding house owned by her aunt, Mrs. A. V. Hill. Built around 1800 as a tavern and boarding house,the U.S. Congress leased the building after the British burned the U.S. Capitol building in 1814, during the War of 1812. By 1825 the new U.S. Capitol building was built, and the building became, at times, a boarding house, a school, and a hotel. It was known as the Old Capitol. By the time of the Civil War in 1861, it was a vacant building, and was converted into a prison.

|

| Old Capitol Building as a prison |

Jordan sent new agents and couriers to Rose, and her home became a center of intrigue. Visitors came and went at all hours of the day and night — generals, senators, and diplomats as well as the young officers. Greenhow wrote of this period in her memoir:

I wish I could present to the mind's eye a picture of Washington as it really appeared under the desecration of the Black Republican rule. Those of its former population who remained from necessity or other causes had disappeared entirely from the surface of society. A new people had taken their places, as distinct and marked in their characteristics as any barbarian race that ever overran Christendom, and who, in their insolent pride of conquest, speedily effaced every landmark of civilisation.

The city was filled to overflowing with greedy adventurers seeking office. Day after day, and month after month, the resistless tide, with black glazed carpet-bag in hand, came rolling in. I sometimes thought them the lost tribes of Israel, who, sniffing from afar the golden harvest, had pierced the confines of eternity and found their way over. Every thoroughfare - every public building - doorway, and corridor, and steps - were blocked up by these sturdy beggars, who came to demand the spoils of victory; and who, disdaining the accommodation of hotel or lodging-house, ate their meals out of those same black glazed carpet-bags, on the highways or byways, and slept like dogs in a kennel.

Add to all this the thousands of drunken demoralised soldiers who filled the streets, crowding women into the gutters, with ribald and obscene observations, and sometimes with more personal insult. It was even difficult to look from the windows without the sense of decency being shocked; and the public squares, which were once such favourite resorts, had now become the chosen places of debauchery and crime. The schools throughout the city had been closed, as it was no longer safe for children to go into the street.

Upon no class of the community did this total abnegation of all the laws, both human and divine, tell with such saddening effect as upon the free coloured population, especially the women, whose sober industrious habits of former days had given place, under the influence of the new order of things, to the most unbridled licentiousness, and who were to be seen at all public places bedecked in gorgeous attire, sharing the smiles of the volunteer officers and soldiers with the republican dames and demoiselles. I have frequently received the answer, when I have sent to demand the services of a negro serving-woman, 'that she would not come, for the reason that she had an engagement to drive or walk with a Yankee officer.'

On August 11, 1861, Greenhow sent another dispatch to Jordan. In precise detail, she reported the location and status of every fortification around Washington, including their armaments and garrison strength. She commented on the political views of key officers. She described the defensive forces ringing the city: their dispositions, weapons, even the number of mules and wagons.

|

| Allan Pinkerton |

Allan Pinkerton was the head of the recently formed Secret Service. He watched Greenhow because of her wide circle of contacts on both sides of the sectional split. He eventually placed her under house arrest at her home at 16th and H Streets, NW.

Greenhow wrote of her arrest:

On Friday, August 23, 1861, as I was entering my own door, on returning from a promenade, I was arrested by two men, one in citizen's dress, and the other in the fatigue dress of an officer of the United States Army. This latter was called Major Allen, and was the chief of the detective police of the city. They followed close upon my footsteps. I had stopped to enquire after the sick children of one of my neighbours, on the opposite side of the street. From several persons on the side-walk at the time, en passant, I derived some valuable information; amongst other things, it was told me that a guard had been stationed around my house throughout the night, and that I had been followed during my promenade, and had probably been allowed to pursue it unmolested, from the fact that a distinguished member of the diplomatic corps had joined me, and accompanied me to that point. This caused me to observe more closely the two men who had followed, and who walked with an air of conscious authority past my house to the end of the pavement, where they stood surveying me.

I continued my conversation apparently without noticing them, remarking rapidly to one of our humble agents who passed, 'Those men will probably arrest me. Wait at Corcoran's Corner, and see. If I raise my handkerchief to my face, give information of it.' The person to whom this order was given went whistling along. I then put a very important note into my mouth, which I destroyed; and turned, and walked leisurely across the street, and ascended my own steps. A few moments after, and before I could open the door, the two men above described rapidly ascended also, and asked, with some confusion of manner, 'Is this Mrs. Greenhow?' I answered, 'Yes.' They still hesitated; whereupon I said, 'Who are you, and what do you want?' 'I come to arrest you.' 'By what authority?' The man Allen, or Pinkerton (for he had several aliases), said, 'By sufficient authority.' 'Let me see your warrant.' He mumbled something about verbal authority from the War and State Departments, and then both stationed themselves upon either side of me, and followed into the house. I rapidly glanced my eye to see that my signal had keen understood, and remarked quietly, 'I have no power to resist you; but, had I been inside of my house, I would have killed one of you before I had submitted to this illegal process.' They replied, with evident trepidation, 'That would have been wrong, as we only obey orders, and both have families.'

. . . I took a rapid survey of the two men, and in that instant decided upon my own line of conduct; for I knew that the fate of some of the best and bravest belonging to our cause hung upon my own coolness and courage. By this the house had become filled with men; who also surrounded it outside, like bees from a hive. The calmness of desperation was upon me, for I recognised this as the first step in that system of infamy which was yet to hold up this nation of isms to the scorn of the civilised world. This was the first act of the new copartnership of Seward, M'Clellan,& Co., - the strategic step, on coming into power, of the young general so lauded - an attack upon women and children, and a brilliant earnest of the laurels to be won on his march to Richmond.

I asked, after a few moments' survey of the scene, 'What are you going to do?' 'To search,' Allen replied. 'I will facilitate your labours;' and, going to the mantel, I took from a vase a paper, dated Manassas, July 23, containing these words - 'Lt.-Col. Jordon's compliments to Mrs. R. Greenhow. Well, but hardworked' - the rest of the letter being torn off before it reached me, some ten days before, through the city post-office. I suspected its delicate mission, so kept it, from an instinct of caution, and had shown it to Major Bache, of U. S. A., Captain Richard Cutts, Wilson, of Massachusetts, and several others. I threw it to Allen, saying, 'You would like to finish this job, I suppose?'

. . . My cool and indifferent evidently disconcerted the whole party. They had expected that, under the influence of the agitation and excitement of the trying position, I should have been guilty of some womanly indiscretion by which they could profit. An indiscriminate search now commenced throughout my house. Men rushed with frantic haste into my chamber, into every sanctuary. My beds, drawers, and wardrobes were all upturned; soiled clothes were pounced upon with avidity, and mercilessly exposed; papers that had not seen the light for years were dragged forth. My library was taken possession of, and every scrap of paper, every idle line was seized; even the torn fragments in the grates or other receptacles were carefully gathered together. . . .

The search still went on. I desired to go to my chamber, and was told that a woman was sent for to accompany me. It did not even then flash upon my mind that my person was to be searched. I was, however, all the more anxious to be free from the sight of my captors for a few moments; so, feigning the pretext of change of dress, &c., as the day was intensely hot, after great difficulty, and thanks to the slow movements of these agents of evil, I was allowed to go to my chamber, and then resolved to accomplish the destruction of some important papers which I had in my pocket, even at the expense of life. (The papers were my cipher, with which I corresponded with my friends at Manassas, and others of equal importance.) Happily I succeeded without such a fearful sacrifice.

The detective Dennis little dreamed that a few paces only stood between him and eternity. He rapped at my door, calling 'Madam! madam!' and afterwards opened it, but seeing me apparently legitimately employed, he withdrew. Had he advanced one step, I should have killed him, as I raised my revolver with that intent; and so steady were my nerves, that I could have balanced a glass of water on my finger without spilling a drop.

Shortly after the female detective arrived. I blush that the name and character of woman should be so prostituted. But she was certainly not above her honourable calling. Her image is daguerreotyped on my mind, and as it is an ugly picture, I would willingly obliterate it. As is usual with females employed in this way, she was decently arrayed, as if to impress me with her respectability. Her face reminded me of one of those india-rubber dolls, whose expression is made by squeezing it, with weak grey eyes which had a faculty of weeping. Like all the detectives, she had only a Christian name, Ellen. I began to think that the whole foundling hospital had been let loose for my benefit.

. . . I was allowed the poor privilege of unfastening my own garments, which, one by one, were received by this pseudo-woman and carefully examined, until I stood in my linen. After this, I was permitted to resume them, with the detectress as my tire-woman. During all this time, I was cool and self-possessed. I had resolved to go through the trying ordeal with as little triumph to my persecutors as possible. I had already taken the resolution to fire the house from garret to cellar, if I did not succeed in destroying certain papers in the course of the approaching night; for I had no hope that they would escape a second day's search. My manner was therefore assumed to cover my intentions. I was also sustained by the conscious rectitude of my purpose, and the high and holy cause to which I had devoted my life.

While searching her house, Pinkerton and his men found extensive intelligence materials left from evidence she tried to burn, including scraps of coded messages, copies of what amounted to eight reports to Jordan over a month's time, and maps of Washington fortifications and notes on military movements.

|

| Fragment of an enciphered letter written by Rose Greenhow and recovered by Pinkerton's men when they searched her home following her arrest |

The materials included love letters from Republican Senator Henry Wilson; Greenhow considered him a prize source, and said he gave her data on the "number of heavy guns and other artillery in the Washington defenses." Pinkerton, however, didn't get Wilson's letters: they went to the Secretary of the Senate for safekeeping. Henry Wilson later became vice-president under President Ulysses Grant.

Word spread quickly that federal agents had captured a major figure in Confederate espionage, and that it was a woman. On August 26, both the New York Times and the New York Herald reported Greenhow’s arrest. Pinkerton not only supervised visitors to Greenhow's house, he also moved other suspected Southern sympathizers into it, giving rise to the nickname "Fort Greenhow."

|

Illustration of Greenhow's home

with guards posted outside |

Eugenia Levy Phillips, a friend of Greenhow's who was suspected of being part of the spy ring, was imprisoned with two of her daughters in the attic of Greenhow's home. Eugenia Phillips described it in her journal, “The stove (broken) served us for table and washstand, while a punch bowl grew into a washbasin. Two filthy straw mattresses kept us warm, and Yankee soldiers were placed at our bedroom door to prevent our escape.” Eugenia and Greenhow were not allowed to speak to each other. Mrs. Philips' friend, Edwin Stanton, who was working in the War Department and became Secretary of War in 1862, intervened on her behalf. The Philips women were released a few weeks later, with the understanding that the family would move south. Eugenia Phillips was later arrested by General Benjamin Butler in New Orleans, Louisiana.

|

| Eugenia Phillips |

Among the men who guarded and questioned the prisoners were two Pinkerton agents, John Scully and Pryce Lewis. Other female prisoners were sent to Fort Greenhow, most of them "of the lowest class," as Greenhow called them. She wrote in her memoir:

On Friday morning, the 30th of August, I was informed that other prisoners were to be brought in, and that my house was to be converted into a prison, and that Miss Mackall and myself, and little girl and servant, were to be confined in one room.

After considerable difficulty and consultation with the Secretary of War, another small room was allowed for my child and maid, with the restriction, however, that I should not go into it, as it was a front room, with a window on the street. Subsequently my library was also allotted to me.

My parlours were stripped of their furniture, which was conveyed into the chamber for the use of the prisoners. By this time I had become perfectly callous. Everything showed signs of the contamination. Those unkempt, unwashed wretches - the detective police - had rolled themselves in my fine linen; their mark was visible upon every chair and sofa.

Even the chamber in which one of my children had died only a few months before, and the bed on which she lay in her winding-sheet, had been desecrated by these emissaries of Lincoln, and the various articles of bijouterie, which lay on her toilet as she had left them, were borne off as rightful spoils. Every hallowed association with my home had been rudely blasted - my castle had become my prison. The law of the land had been supplanted by the higher law of the Abolition despot, and I could only say, 'O Lord, how long will this iniquity be permitted?'

. . . On the 16th day of November I received a visit from my sister, Mrs. James Madison Cutts, and my niece, the Honourable Mrs. Stephen A. Douglass, accompanied by Colonel Ingolls, U.S.A. - the permit to see me making the presence of an officer during the interview obligatory, and limiting it to fifteen minutes.

On November 17, 1861, Greenhow wrote to Secretary of State Seward reviewing her arrest and treatment, especially the invasion of her privacy. Her letter was printed in Richmond and New York newspapers. Although this publicity brought sympathy from her family (Ellen Cutts and her daughter Addie Douglas visited shortly before Christmas), it also brought Northern criticism for what was perceived as too lenient treatment of a spy.

On the afternoon of January 18,1862, Greenhow was given two hours to get ready to move: she and Little Rose were taken to the Old Capitol Prison, which was in the same building her aunt had previously run as a boarding house, where John Calhoun had lived and died. Greenhow wrote:

The building itself was familiar to me. The first Congress of United States in Washington had held its sessions there; but it was far more hallowed in my eyes by having been the spot where the illustrious statesman John C. Calhoun breathed his last. The tide of reminiscences came thronging back upon my memory. In the room in which I now sat waiting to be conducted to my cell, I had listened to the words of prophetic wisdom from the mouth of the dying patriot. He had said that our present form of Government would prove a failure; that the tendency had always been, towards the centralisation of power in the hands of the general Government; that the conservative element was that of States' rights; that he had ever advocated it, as the only means of preserving the Government according to the Constitution; that it was a gross slander to have limited his advocacy of those principles to the narrow bounds of his own State; that he had battled for the rights of Massachusetts as well as for those of South Carolina; and that, whenever it came to pass, that an irresponsible majority would override this conservative element, that moment would the Union be virtually destroyed. . .

And now scarce a decade has passed, and his prophetic warnings have been realised; and Abraham Lincoln has brought about the fulfillment of his prophecy.

. . . After the lapse of some half-hour I was taken up to the room which had been selected for me by General Porter. It was situated in the back building of the prison, on the north-west side, the only view being that of the prison-yard, and was chosen purposely so as to exclude the chance of my seeing a friendly face. It is about ten feet by twelve, and furnished in the rudest manner - a straw bed, with a pair of newly-made unwashed cotton sheets - a small feather pillow, dingy and dirty enough to have formed part of the furniture of the Mayflower - a few wooden chairs, a wooden table, and a glass, six by eight inches, completed its adornment . . . The second day of my sojourn in this dismal hole a carpenter came to put up bars to the windows. I asked by whose order it was done, and was informed by the superintendent that General Porter not only ordered it, but made the drawings himself, so as to exclude the greatest amount of air and sunlight from the victims of abolition wrath. Wood remonstrated against the bars, saying that they had not been found necessary; whereupon Porter said, 'Oh, Wood, she (alluding to me) will fool you out of your eyes - can talk with her fingers,' &c.

. . . The portion of the prison in which I was confined was now almost entirely converted into negro quarters, hundreds of whom were daily brought in, the rooms above and below mine being appropriated to their use; and the tramping and screaming of negro children overhead was most dreadful. The prison-yard, which circumscribed my view, was-filled with them, shocking both sight and smell - for the air was rank and pestiferous with the exhalations from their bodies; and the language which fell upon the ear, and sights which met the eye, were too revolting to be depicted - for it must be remembered that these creatures were of both sexes, huddled together indiscriminately, as close as they could be packed. Emancipated from all control, and suddenly endowed with constitutional rights, they considered the exercise of their unbridled will as the only means of manifesting their equality.

In addition to all other sufferings was the terrible dread of infectious diseases, several cases of small-pox occurring, and my child had already taken the camp-measles, which had broken out amongst them. My clothes, when brought out from the wash, were often filled with vermin; constantly articles were stolen. Complaint on this head, of course, was unheeded. Our free fellow-citizens of colour felt themselves entitled to whatever they liked. Several times during this period my child was reduced to a bare change of garments; and the supreme contempt with which they regarded a rebel was, of course, very edifying to the Yankees, who rubbed their hands in glee at the signs of the 'irrepressible conflict.' One day I called for a servant from the window. A negro man, basking in the sun below, called out - 'Is any of you ladies named Laura? dat woman up dare wants you.' And, by way of still further increasing the satisfaction with this condition of things, Captain Gilbert, of the 91st Pennsylvania Volunteers, drilled these negroes just below my window.

A photographer from Mathew Brady's studio came to photograph the mother and daughter together. Sightseers, some of whom were willing to pay $10 for the opportunity, passed by her door to gape at the "indomitable rebel."

So many political prisoners were detained that a two-man commission was set up to review their cases at what were called espionage hearings. In March 1862, Greenhow was summoned to appear before the United States Commissioners for the Trial of State Prisoners- The hearing was held by Major General John Adams Dix, a man Rose had known for many years and for whom she had respect. His fellow commissioner was Judge Edward Pierrepont, who realized it was useless to ask her to take an oath of allegiance, or to give her a parole, promising not to aid the enemy, conditions which other prisoners had agreed to accept.

Although her actions were treasonable, the Lincoln administration was reluctant to have her stand trial. Treason was a hanging offense, but at that time it was almost unthinkable to hang a woman, nor did they want to make her a martyr for the Southern cause. Greenhow was given a choice: either swear allegiance to the Union or be deported to the Confederacy. She agreed to be deported to the South. She had to sign a statement as a condition of her parole that she would not set foot in the Northern states while the war continued.

On May 31, 1862, Greenhow and her daughter were released, on condition that Greenhow stay within Confederate boundaries. They were escorted to Fort Monroe at Hampton, Virginia, at the southern tip of the Virginia peninsula.

|

| Fort Monroe |

From there, she and her daughter went on to Richmond, Virginia, where Greenhow was hailed by Southerners as a heroine.

|

| Richmond, Virginia |

She wrote:

I arrived in Richmond on the morning of the 4th, and was taken to the best hotel in the place, the Ballard House, where rooms had been prepared for me. General Winder, the Commandant of Richmond, came immediately to call upon me, so as to dispense with the usual formality of my reporting to him. On the evening after my arrival our President did me the honour to call upon me, and his words of greeting, 'But for you there would have been no battle of Bull Run,' repaid me for all that I had endured, even though it had been magnified tenfold. And I shall ever remember that as the proudest moment of my whole life, to have received the tribute of praise from him who stands as the apostle of our country's liberty in the eyes of the civilised world.

|

| Jefferson Davis |

Mary Chesnut wrote in her diary in June:

Mrs. Rose Greenhow is in Richmond. One-half of the ungrateful Confederates say Seward sent her. My husband says the Confederacy owes her a debt it can never pay. She warned them at Manassas, and so they got Joe Johnston and his Paladins to appear upon the stage in the very nick of time.

|

| Mary Chesnut |

For the next year, Greenhow nursed in the hospitals, knitted and sewed for the soldiers. She also helped to identify John Scully and Pryce Lewis, two Pinkerton agents who had guarded and interrogated her while under she was house arrest. They arrived in Richmond on February 26, posing as two British cotton merchants, and checked into the Ballard Hotel. Chase Morton, who had been arrested by Lewis and Scully in Washington a couple of months earlier on accusations of spying, been sent south. Now he recognized Lewis and Scully at the hotel.

|

| Pryce Lewis |

Greenhow had been writing her memoirs, and by the summer of 1863, it had been decided that she would go to Europe to get them published in London. She would also try to obtain aid for the Confederacy by offering cotton in return for ships and military supplies.

|

| Alexander Boteler |

Greenhow wrote a letter to Alexander Boteler, who was on General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's staff, on June 19, 1863:

My good and kind friend - You will I am sure be glad to know that all things prospered here according to my wishes I saw the President this morning and he affords me every facility and and in carrying out my mischief. I shall leave here on Tuesday or Wednesday. Tuesday certainly as the [illegible name of ship] upon which I will go will sail the latter part of the week on Friday from Wilmington to Bermuda. Once I shall take out as much cotton as I can.

I shall be very much engaged for the remainder of my sojourn here in getting ready. I sincerely wish you were here to aid me in some other matters. I know how selfish this wish must appear, when I know how your heart has ached to get to your dear family--you have been so kind to me that I feel as if your family were almost old friends. Pray make them like me for it will bring great pleasure when I return to know them. I will write again when I leave here and also from Wilmington for I have the vanity to suppose that you will take an interest in my movements.

I cannot tell you my friend how highly I appreciate your friendship and offer you my heartfelt congratulations on being [illegible] and true enjoyment of this society [illegible] to you.

Believe me always your true friend

Rose O'Neal Greenhow

PS - I hope you will be able to read this as it is written under high pressure.

Votre toujours

R G

Greenhow's letter to Jefferson Davis, July 16, 1863:

Charleston July 16th [1863]

To The President

My dear Sir

I arrived here yesterday (Wednesday) at noon after rather a fatiguing travel from Richmond, not stopping by the wayside long enough to wash my face.The only thing to mark the journey was the excitement and anxiety manifested by all classes to hear the news from Richmond, and especially from Lee's army, and many a sigh of relief was uttered. When when I spoke of his calm confident tone. I endeavored also to empress upon every one your conviction as to the necessity of reinforcing the army by the most rigorous means.

Just as I left Richmond news of the fall of Fort Hudson had been received which was confirmed by the intelligence of the wayside. On reaching Wilmington the situation of Charleston became the engrossing subject of conversation and of interest, which was not diminished by the accounts received from time to time by passengers who got on the principle portion of whom were from Charleston or the vicinity. Doubt and anxiety as to the result was the general tone of the people, and occasionally severe animadversions upon the conduct of the military affairs, especially instancing the supineness, in the construction of the defenses. These I mention--nor [do] I attach importance to criticism of this nature but rather to show you the temper & spirit of the people. Soon after getting with the territory of S.C. hand bills were distributed along the route setting forth the imminent peril of Charleston and calling upon the people for 3000 negro's to work on the defenses. On nearing the city the booming of the heavy guns was distinctly heard, and I feared that the attack had been going on with but little intermission for several days. I omitted to mention also that the cars coming were laden with cotton and in many instances carriages & horses also being sent to the interior, showing the sense of insecurity which very generally prevails.

Friday-- Knowing upon what slight grounds panics are often based, I did not even give due credit to these indications as to the actual state of affairs but put aside my letter until I could obtain a better insight into them. --And I now resume my letter, feeling that I can confidently state the result, and only wish that I could honestly make a more cheering exposition. The impression here that Charleston is in great danger is sustained by the opinion of the Military Authorities. I saw Genrl. Beauregard who came to call upon me, and had a very long conversation with him, and he is deeply impressed with the gravity of the position. He says that three months since he called upon the planters to send him 2000 negro's to work upon the fortifications at Morris Island and other points and that he could only get one hundred, and that they would not listen to his representations as to the threatened danger.

. . . He told me that he had plenty of men for the present, and thus only needed the heavy guns & mortars have talked with a number of men of high military position as also prominent Citizens, and altho they blamed Beauregard in the first instance for inactivity in not fortifying the known weak point of Charleston, and that he should have allowed himself to be taken at a disadvantage. All now concur in believing that every effort will be made to defend and save the City--her fate stands trembling in the ballance.

. . . I tell you this as I think it right that you should know all that is said; and that it is not idle street gossip but comes to me from men in high position. At the same time I know you to be too wise to be unduly influenced by the best founded gossip, without more substantial grounds. . .

Vizitelli of the London News who has been down there has just left me and given me some very interesting details of that region . . . He says that the European world will never allow the reconstruction of the American Union--that their sympathies are naturally with the Anglo-Saxon race who are represented in the South that they will say let them alone they can accomplish their destiny with[out] us--but the moment they found that the chances are that we are likely to be overcome by that Northern race--that moment will they rise up to prevent it. He thinks our people unduly depressed now by the events at Vicksburg &-- and is writing a series of articles (incog.)on the subject one of which for the Courier he has submitted to me. He says he is very glad that I am going to England as he knows I will be useful, and gives me some very good letters [word torn out]

I have once more my kind friend to trouble you--will you cause the necessary directions to be sent me here so that I may be enabled to go from Wilmington and together with the permit to ship cotton for my expenses, and if it be not possible to ship the whole amount required by any one vessel can be distributed amongst the number so as to enable me to take the necessary amount . . . I shall remain here until Wednesday or Thursday and shall hope to get a letter from you--which I can frame as an heirloom for my children also . . . I will continue to write to you but will promise not again to inflict such a long letter as I consider by this . . .

|

| Greenhow's letter to Jefferson Davis, July 16, 1863 |

Greenhow made the first entry in her diary on August 5, 1863, the night she boarded the Confederate blockade runner Phantom, bound for Bermuda. The vessel was spotted by the watch of the USS Niphon off New Inlet, and a larger blockading ship, the Mount Vernon, chased the Phantom, but was unable to catch up to it.

Letter to Alexander Boteler, August 13, 1863

St George Bermuda

August 13th [1863]

My Good friend

I have as you will see arrived here in despite of Yankee cruisers who gave us a close chase all the way. I was seasick of course but I am now entirely recoverd and enjoying the dolce faneanti of this seducing climate with its beautiful tropical trees and fruits.

I shall leave here the middle of the coming week en route for Southampton. And when I reach this point I will tell you your impressions of matters and things. I have met with kind friends Rev. Mr. and Mrs. Walker with whom I spend all my time are very charming and cultured people. He is certainly a most indefatigable and valuable officer to the Confederacy and by his prudence and high trust conduct him the consideration of all here, and is there by enabled to render service to the country of a magnitude that would be startling if it were prudent to speak yet.

My good friend I thank you for your salutation and kind wishes towards me. I trust that I shall always be as fortunate as to retain the officers whose appreciation elevates me and my own esteem.

With my best wishes and friendship,

Rose ON Greenhow

|

| Georgiana Walker |

Once in London, she made arrangements for publication of her book, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington. It was published just two months after her arrival and it sold well in Britain.

|

Title page of

My Imprisonment

and the

First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington |

Her book began with the following passage:

Whether a faithful record of my long and humiliating imprisonment at Washington, in the hands of the enemies of my country, will prove as interesting to the public as my friends assure me it is to them, I know not. It is natural for those who have suffered captivity to exaggerate the importance and interest of their own experiences; yet I should not venture upon publishing these notes and sketches merely as a narrative of indignities heaped upon myself personally.

It is hoped that the story may excite more than a simple feeling of indignation or commiseration, by exhibiting somewhat of the intolerant spirit in which the present crusade against the liberties of sovereign States was undertaken, and somewhat of the true character of that race of people who insist on compelling us by force to live with them in bonds of fellowship and union.

. . . After repeated and intolerable aggression upon the rights of these States - accompanied and aggravated by an insulting tone of moral superiority, until a union with such communities was no longer to be endured by any high-spirited people - they at length stirred up a furious and desolating war. For two years a torrent of blood has flowed between their people and my people. The noble State of Virginia, with which I am most nearly connected, has been devastated by hosts of barbarous invaders - always overthrown indeed in the field before Southern valour, but always destroying and plundering where they found the country unprotected; whilst my own dear native State of Maryland has been subject to a still more stinging and maddening oppression, in the utter destruction of all her liberties, and in the establishment of a brutal and vulgar military despotism, which has reduced the gallant old State to the debased condition of Poland . . .

To me, therefore, the days of my former abode in Washington seem to belong almost to another state of being. That time - when I, in common with all our people, looked up with pride and veneration to the banner of the stars and stripes - appears to be now with the years before the Flood. I look back to the scenes of that period through a haze of blood and horror. Those men whom I once called friends - who have broken bread at my table - have since then stirred up and hounded on host after host of greedy invaders, and precipitated them upon the beloved valleys where my kindred had their peaceful homes. Many who were dear to me have been slain, or maimed for life, fighting in defence of all that makes life of value. Instead of friends, I see in those statesmen of Washington only mortal enemies. Instead of loving and worshipping the old flag of the stars and stripes, I see in it only the symbol of murder, plunder, oppression, and shame! and, like every other faithful Confederate, I dwell with delight on the many glorious fields where this dishonoured standard has gone down before the stainless battle-flag of the Confederacy.

. . . It will be seen that I was well aware from an early period of the dark designs of the Abolition leaders at Washington, and that while they were holding publicly the language of patriotic zeal for the constitution and the law, they were already meditating, and preparing, all the dreadful scenes of lawless outrage and spoliation which have since that time rendered their names odious to the whole world, It was well known to me what fate they were reserving for my own native State, and what diabolical agencies they were setting to work over all the country, both to destroy the Confederate States and to crush out the liberties of the North.

The chief projectors of all these horrors, too, were well aware that I knew their plans and machinations intimately; and that, weak woman as I was, I possessed both the means and the spirit to throw serious obstacle in their way. Hence the keen and jealous surveillance by which my every motion was observed and noted, even long before my arrest. Hence, also, the useless series of torments and provocations to which I was subjected - the changes in my place of imprisonment, and the many attempts to entrap me into a betrayal of myself or the Confederate cause. Hence the long and wearisome captivity, to break my spirit, or goad me into undignified bursts of indignation - in all of which I trust I may flatter myself that they signally failed.

Satisfied thoroughly of the justice and sacredness of our great cause, thinking only of the gallant struggle into which my kindred had thrown themselves, I was enabled, not only to 'possess my own soul' and keep my own counsel, but also to establish and maintain a continuous correspondence with Virginia, and reveal certain contemplated military movements of enemy in time to have them thwarted by our generals.

|

| Portrait of Greenhow in her Memoir |

In her memoir, she wrote her opinions about the war, politics, government, race and slavery:

Slavery, although the occasion, was not the producing cause of the dissolution. The cord which bound the sections together was strained beyond its strength, and, of course, snapped at the point where the fretting of the strands was greatest.

The contest on the part of the North was for supreme control, especially in relation to the fiscal action of the Government. This object could not be fully attained by a mere numerical majority. A majority of States was also necessary. To secure this majority, and thus complete the political ascendency the North, the policy of 'no more Slave States' was formally set forth.

A political party was formed, whose sole principle was the exclusion of slavery from the territories. There was no moral sentiment involved in this. It did not alter the status of slavery. It made not a human being free; nor did it propose to do so. 'Sir,' said Mr. Webster in the Senate, 'this is not a moral question: it is a question of political power.' Lord Russell has more recently corroborated this bold assertion, by saying, that 'this was a struggle on one side for supremacy, and on the other for independence.'

. . . It is true that the anti-slavery fanaticism was brought to bear; and it is also true that there followed a rancorous agitation which divided churches, rent asunder political parties, diminished and embittered the intercourse of society, and unfitted Congress for the performance of its constitutional duties, and resulted in the estrangement of the Southern people from their Northern connection. But this estrangement was not an active or stimulating motive, and manifested itself rather in the want of any general anxiety to restrain the movement for disunion.

Equally unfounded is the allegation that the secession of the South originated in the exasperation of a defeated party, and hostility to the successful candidate. The stern protest of the Southern people, free from all party violence and recklessness, indicated a thorough knowledge of the extent and depth of the grievances inflicted upon them; and subsequent events have proved that they had both wisdom and heroism adequate to evolve the proper remedy, and firmly to apply it. . .

It is a most remarkable fact, that while in their native Africa the race has made no progress, while in the mock Republic of Hayti or brutal despotism of Soulouque, in Jamaica and the British West Indies, the emancipated slaves have retrograded to barbarism, while even in our own North the free black race is generally found in the gaols, or poor-houses, or hospitals, the asylums of the deaf and dumb, the blind or insane, or in pestilent alleys or cellars, amid scenes of destitution and infamy, yet in Africa alone, a colony of emancipated slaves, born and raised in the much-abused South, and trained and manumitted by Southern masters, we find the only hope of the African race, and the only success they have ever achieved out of bondage.

. . . I do not propose to attempt the vindication of the Institution which has been the fruitful theme of reproach and denunciation amongst the opponents of Southern independence. The English writers who discuss this subject seem to confine themselves to the consideration of the abstract principle of slavery, and entirely overlook the facts and circumstances of the case. . .

If the question were simply whether it would not be better for the South to have four millions of intelligent, industrious, and valiant freemen in the place of four millions of African slaves, it would be neither so delicate nor difficult of solution.

But the question which taxes the practical statesmanship and philanthropy of the Southern people is of a far graver character. It is this. Two races - one civilised, the other barbarous - being locally intermingled, what does the good of society require - the freedom or servitude of the barbarous race?

The South believe that the freedom of the blacks, under such circumstances, would result certainly in their final extermination, and that servitude is best adapted to their intellectual and moral condition. . .

The North American Indians were a race of warriors, with far higher intellectual capabilities than the negro, and not inheriting that unutterable prejudice against amalgamation which exists against the negro. But at the same time, there being no motive of interest in the superior race to protect them, they have been driven from their hunting-grounds, which at no distant period embraced half of the North American continent, to a few acres on the confines of civilisation, which they inhabit by the sufferance of the dominant race.

In support of the usages of civilisation in favour of this law of race, I can cite an example which comes within my own immediate knowledge, and which is uninfluenced by the fanaticism and demagogism which attach to the negro question. In California, there are between sixty and seventy thousand Chinese, being about one-seventh of the whole population. They are a civilised, industrious, and most useful people. Yet they cannot be naturalised, cannot bear witness in court, cannot intermarry with the white race, or exercise a single right of citizenship, except pay taxes.

The wisdom of the policy of the South in regard to this inherited responsibility is abundantly vindicated by the very aspect which the Institution of Slavery now presents to the world. For thirty years its enemies have unceasingly assailed it by every agency of mind and heart. The pulpit, the press, hostile legislation, secret societies, armed robbers, have all been employed to excite discontent and insurrection in the Southern States.

. . . Nowhere on earth, not even in happy England, rejoicing in peace, does there exist between the various classes of society such harmony, such sympathy, as the South exhibits in the midst of her trials. Surely the condition of such a social commonwealth must rest upon the solid foundation which supports all civil institutions - the good of the whole State.

But we are asked, 'Do not your statutes withhold any legal enforcement to the marriage relations amongst slaves?' I beg my readers to have this objection properly stated. It should be borne in mind that we have not taken from them any rights which they had ever recognised or conferred among themselves. The race, as we found it, was destitute of any such institution, or even the knowledge of it. Nevertheless, it is true that our laws are justly chargeable with the reproach of not having secured to them this blessing of civilisation. But what the law has failed to do, religion and usage have effected. The institution of marriage does exist among slaves, and is encouraged and protected by their owners.

|

| Photograph of Greenhow taken in London |

Letter to Alexander Boteler, December 10, 1863:

2 Conduit Street

Regent Street, London

December 10 [1863]

To Hon. A. A. Boteler

My good friend

I suppose from your unbroken silence that you cannot have received any of my letters. I wrote to you from Bermuda and also from London on my arrival here. How anxiously I look for letters from home it would be impossible for me to tell you. All the accounts come through the Yankee press--Just now we have the news of Bragg's disastrous defeat and falling back from Lookout Mountain - with loss of 60 pieces of artillery small arms &c. and 8000 prisoners - I give a wide margin to this for the usual exageration. But the effect is most depressing. This news has brought down the Confederate loan from 60 to 31. My friend you know not the importance of sending correct information, which can be used so as to counteract the Yankee accounts. I believe that all classes here except the Abolitionists sympathize with us and are only held back from recognizing us for fear of war with the United States.

. . . I am myself sanguine of the events of the next few months. . . . I would write you many interesting particulars but the publication of the late intercepted letters is a good warning to me to be careful. If you will get from Mr. Benjamin a cipher and use my name as the key, I can then tell you many things--your letters to me will not need the same chance as the mails going out seem to escape. Direct to Maj Walker at Bermuday and he will forward them to here - You don't know how my heart grows sick when the mail comes without letters for me, and it is important that I should have news as I have the means of placing it in proper quarters.

Tomorrow morning I leave at an early hour for Paris, where I expect to have a nice time. I have been occupied for the last two days so incessantly that I have not had time to think. Your predictions have been more than fulfilled--for no stranger has ever been received more kindly than have I, and from this time forward I'm bound to dispute the charge against the English of coldness or inhospitability. I wish I could write fully and freely but the fear of seeing myself in the NY Herald restrains my desire to tell you many things. I trust that I should be at home before the winter is over.

|

| Letter to Alexander Boteler, December 10, 1863 |

While in France, Greenhow was presented at the court of Napoleon III. She wrote in her letter to Boteler, February 17, 1864:

157 New Bond Street

London Feb 17th [1864]

. . . I have had a very pleasant time , and accompanied my wishes in some instances beyond my hopes - I have just returned from Paris where I spent two months very pleasantly -

I had the honor of an audience with the Emperor - obtained without aid from any one as indeed where no one representing us who could obtain so much upon his own account. I was treated with great distinction great kindness, and my audience in Court Circles was pronounced "une grande sucess - and altho the Emperor was lavish of expressions of admiration of our President and cause there was nothing upon which to hang the least hope of aid unless England acted simultaneously - the French people are brutal ignorant and depraved to a degree beyond description and have no appreciation of our struggle they believe it is to free the slaves and all their sympathies are really on the Yankee side. The Emperor sympathises with us but altho ruling with despotic power he is obliged to be watchful and wary as any false step would be his ruin and he dare not take a step unless England joins him - For he is not blind to the fact that without such co-operation privateers from British Ports under Yankee flag would swarm in the Northern seas. . . .

|

| Napoleon III |

My belief is that from England alone are we to expect material aid The better classes here are universally in our favor and the debates now going on in both houses of Parliment show the strong opposition to the Gov -

|

| Thomas Carlyle |

. . . So it is still a question of hope deferred with us. On Monday evening I spent at Mr. Carlysle - he is a warm and earnest advocate of our cause and were he this he would do anything for us - I suggested that he write something - which he said he would take into consideration Tuesday Morning I went to see Cardinal Weisman and was deeply gratified by his earnest sympathy - I also suggested that he could do us good by some public manifestation of his views. In the afternoon of the same day I dined with Mr & Mrs Roebuck and had a very interesting conversation with him. I am to dine there on thurs and go with him afterwards to the House of Parlament-

. . . How much I long to be again amongst my own people I cannot tell you - I have had every thing to gratify me as no stranger has ever been better recieved - unacknowledged unrepresented as we are. Still I long for my own home and the sight of our toil worn soldiers will be a more welcome sight that all the splendor I have witnessed - by the by I had almost forgotten to tell you that I went to the grand state ball at the Tuileries, and was the only stranger mentioned in the description of the ball. Do not you or my other friends forget me I believe that I am useful here but I long to be at home.

With my most sincere and friendly regards

Rose O'N Greenhow

|

| Victoria |

By prior arrangement, Florence Greenhow Moore went abroad to meet her mother in Europe. Greenhow was presented to Queen Victoria, and also pressed Lord Palmerston, the prime minister of the United Kingdom, to recognize the Confederate States of America. She successfully negotiated with Charles Francis Adams, U.S. Minister to France, and a former guest in her home, for the release of a young lieutenant, Joseph D. Wilson. Wilson had been captured when the USS Kearsarge sank the CSS Alabama off the coast of France in June 1864.

|

| Joseph D. Wilson |

One of Greenhow's frequent companions in England was Lady Georgiana Fullerton, whose brother was the second Earl of Granville.

|

| Lady Georgiana Fullerton |

In 1864, Greenhow reportedly became engaged to Granville George Leveson Gower, Lord Granville, a recent widower.

|

| Granville George Leveson Gower |

Before leaving Europe, she wrote in her diary:

A sad sick feeling crept over me, of parting perhaps forever, from many dear to me . . A few months before I had landed a stranger--I will not say in a foreign land--for it was the land of my ancestors--and many memories twined around my heart when my feet touched the shores of Merry England--but I was literally a stranger in the land of my fathers and a feeling of cold isolation was upon me.

|

| Pensionnat du Sacre-Coeur,now the Rodin Museum in Paris |

Before leaving Europe, Greenhow placed Little Rose in the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Paris. On August 19, 1864, Greenhow left on her return trip to the Confederacy. She traveled on the Condor, a British blockade runner, which sailed to Canada. James P. Holcomb, another Confederate agent, boarded the ship before it turned southward.

|

| James P. Holcomb |

The U.S. counsel in Halifax learned the names of the Condor's passengers and their destination. He sent the information to Secretary of State William Seward, who forwarded it to Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles. Welles alerted Acting Rear Admiral S.P. Lee, who was in charge of the North Atlantic Blocking Squadron.

|

| USS Niphon |

After midnight on October 1, 1864, the Condor approached the mouth of the Cape Fear River near Wilmington, North Carolina. At 3:40 a.m., lookouts aboard the Niphon spotted the Condor and opened fire. The Condor was only 800 yards off Fort Fisher, which opened fire against the U.S. ships with long-range rifled artillery. The Condor ran aground on shoals, but it was close to the guns of Fort Fisher, and the federal ships could not move closer without being hit by rocket fire.

|

| August Hobart-Hampden |

Greenhow, who feared capture by Union troops, insisted on trying to escape in a rowboat with several others. The captain, August Hobart-Hampden, discouraged her: he assured Greenhow that in the morning, the ship would float free with the rising tide, and that the Confederate guns of Fort Fisher would keep the Federals at bay. Greenhow demanded to leave the ship and, wearing a heavy black silk dress, she entered a small boat with Holcombe, Wilson, and a few other men. She carried a leather valise with dispatches to the Confederate government, and 400 gold coins, worth about $2,000, in a bag hanging from a cord around her neck. Waves battered the small boat and tossed everyone aboard into the water. The men clung to the overturned boat and survived, but Greenhow, weighed down by her voluminous dress and the gold, immediately sank and drowned.

Those who had remained on the Condor escaped the next day.

|

| Greenhow's note to her daughter, Little Rose |

When Greenhow's body was recovered near Wilmington, a copy of her memoirs was found hidden in her clothes. Inside the book was a note for her daughter, Little Rose, which read:

London, Nov 1st 1863

You have shared the hardships and indignity of my prison life, my darling; And suffered all that evil which a vulgar despotism could inflict. Let the memory of that period never pass from your mind; Else you may be inclined to forget how merciful Providence has been in seizing us from such a people.

Rose O'N Greenhow

She was honored with a military funeral and burial in Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington, North Carolina. After a Catholic Mass at St. Thomas the Apostle, the funeral cortege of eight carriages and scores of mourners on foot accompanied Greenhow’s coffin to the cemetery in heavy rain.

|

| Greenhow's Obituary |

Greenhow did not have a will when she drowned. In a deposition given after her death, an attorney, Alfred M. Waddell, testified that that Greenhow had given him a will during her return voyage on the Condor. He testified that when the lifeboat capsized, he had the will in his jacket pocket. As the boat overturned, one of the men on board grabbed for something to cling to, and caught his pocket, ripping it and the enclosed will from his jacket. The court ruled that since he was unable to produce the will, Greenhow died intestate, and her belongings were to be sold at public auction. Greenhow's diary had remained on board the Condor; a leather trunk containing her belongings was removed from the ship and sold at auction.

|

| Alfred M. Waddell |

Little Rose Greenhow was in the Sacred Heart Convent when her mother died, and remained there until 1866. After the war ended, American friends took her home to live with her sister, Florence Greenhow Moore, who by then were living in Rhode Island. Little Rose married a West Pointer, Lieutenant William Penn Duvall, on November 30, 1871 in Newport, Rhode Island. She gave birth to one daughter, Lee Duvall. William Duvall enjoyed a distinguished military career, but he and Rose eventually divorced. After her divorce, Rose appeared on the stage for a time. She returned to France, became deeply religious and retired from public view.

In 1888, the Ladies Memorial Association marked Greenhow's grave with a cross that read

Mrs. Rose O'N. Greenhow

A Bearer of Dispatches to the Confederate Government.

|

| Greenhow's grave |

Greenhow's diary was stored with the papers of David L. Swain, a former governor of North Carolina and president of the University of North Carolina, who died in 1868, four years after Greenhow. No one noticed the diary until the state archivist, who spent years cataloguing the Swain papers, identified it as Greenhow’s diary. On November 17, 1965, Dr. H. G. Jones made the following entry in his own journal: “I found the diary of Rebel Spy Rose O’Neil Greenhow in the archives unidentified. Apparently never used.”

|

| David L. Swain |

Greenhow’s diary, dated August 5, 1863 to August 10, 1864, and describing her mission in detail, is held in the North Carolina State Archives in Raleigh. The papers seized from Greenhow's home by Pinkerton are now held by the National Archives and Records Administration, which has digitalized and made them available in the Archival Research Catalog.

Edward C. Fishel, a historian of Civil War intelligence, dismissed the value of any information that Greenhow may have provided Beauregard as greatly overblown. In his book, The Secret War for the Union, Fishel makes the argument that Greenhow's report to Beauregard consisted of general and stale information that probably was derived from common gossip in Washington society. Greenhow dispatched two messages to Beauregard, one on July 9th and the second on July 16th, warning him of McDowell's planned advance. However, there is no hard evidence that she had specific details regarding the Union plan, which had been decided on in late June, or that her sources had access to any information beyond that which was already freely available in the newspapers and parlors of Washington, or to any casual observer watching regiments march across the Potomac River bridges. Most accounts of Greenhow's exploits claim that the dispatch of Joseph Johnson's army from the Shenandoah to Manassas, which made the key difference in the battle, was a result of the intelligence provided by Greenhow, but this claim may be dubious, as Beauregard did not immediately request reinforcements upon receiving Greenhow's report.

|

| Greenhow's Code Key |

Some people say that Rose Greenhow's ghost has been seen walking Kure Beach near Fort Fisher.

No comments:

Post a Comment