CONTINUED FROM PART ONE

Susan Anthony wrote to her friend, Martha Coffin Wright:

|

| Martha Coffin Wright |

Jan. 7, 1861 —

Dear Mrs. Wright—Here we are—Mrs. Stanton, Green & I— alive— after the Buffalo Mob —

I have forgotten whether I have asked you to have the Auburn Convention published in your weekly papers to date— so send this—

We have dispatched notes of the Buffalo riot— to Tribune, Standard & Liberator & hope some of them will get out to the world—There was a more determined union to put down a speech, not to the mind of the masses— but we must face it through—

Mrs. Stanton's pen is scratching on free speech— She is getting a grand speech— & we are doing nicely, only want to see the faces of Powell & May— Good Bye—S. B. A.

|

| Samuel May |

Later in January, before a major antislavery rally in Syracuse, New York,, Samuel May and Susan B. Anthony were threatened with violence by an angry crowd that stormed the building. The rally was cancelled, and the mob paraded through the streets with effigies of May and Anthony, finally burning them in the center of town. An account was reported in the February 15 issues of The Liberator:

A Burlesque Procession — Burning in Effigy and other Outrageous Proceedings. Last evening a mob of about twenty rowdies and loafers assembled at the usual rendezvous, James McGurk’s Grocery, in the Courier Building, and obtaining a Band and several transparencies and effigies which had been previously prepared by the leaders, these miserable tools marched through several streets of our city, and finally halted on Hanover Square, where some disgusting exercises took place, a few brutal speeches were made, and the effigies burned in a bonfire made upon the Square … one intends to represent Miss Anthony, and the other Rev. Mr. May. … The transparencies included: The Rights of the South Must Be Protected! Freedom of Speech, But Not of Treason!

|

| Lucretia Mott |

The State Woman's Rights Convention was held in Albany, February 7 and 8. Mr. Garrison, Mrs. Rose, Lucretia Mott and many of the old brilliant galaxy were among the speakers. They little thought that this was the last convention they would hold for five years, that a long and terrible war would cast its shadow over every household before they met again, that differences would arise in their own ranks, and that never more would they come together in the old, fraternal spirit that had bound them so closely and given them strength to bear the innumerable hardships which so largely had been their portion.

After the Albany meeting, Miss Anthony at once began preparations for the National Woman's Rights Convention in New York in May. The date was set, the Tabernacle secured and many of the speakers engaged, but in the meantime the affairs of the nation had become more and more complicated; the threatened secession of the Southern States had been accomplished; the long-expected, long-dreaded crisis seemed close at hand; the people were uncertain and bewildered in the presence of the dreadful catastrophe. All thought, all

|

| Abraham Lincoln |

interest, all action were centered in the new President. The whole nation was breathlessly awaiting the declaration of Lincoln's policy. To call any kind of meeting which had an object other than that relating to the preservation of the Union seemed almost a sacrilege. Letters poured in upon Miss Anthony urging her to relinquish all idea of a convention, but she never had learned to give up.

Even after the fall of Sumter and the President's call for troops, the letters were still insisting that she declare the meeting postponed; but it was not until the abandonment of the Anti-Slavery Anniversary, which always took place the same week, and until she found there were absolutely no speakers to be had, that she finally yielded.

About this time she takes care of a sister with a baby, and writes Mrs. Stanton:

"O this babydom, what a constant, never-ending, all-consuming strain! We should never ask anything else of the woman who has to endure it. I realize more and more that rearing children should be looked upon as a profession which, like any other, must be made the primary work of those engaged in it. It can not be properly done if other aims and duties are pressing upon the mother."

And yet so great was her spirit of self-sacrifice that in this same letter she offers to take entire charge of Mrs. Stanton's seven children while she makes a three months' trip abroad. At a later date, when caring for a young niece, she says:

"The dear little Lucy engrosses most of my time and thoughts. A child one loves is a constant benediction to the soul, whether or not it helps to the accomplishment of great intellectual feats."

In Kansas, R.C. Satterlee of the Kansas Herald wrote an article in the newspaper accusing

|

| D.R. Anthony |

Susan's brother, D.R. Anthony, of being a coward. They met on the street and exchanged gunfire. Satterlee was killed. D.R. Anthony was arrested, but a jury found him not guilty of murder.

D.R. Anthony served during the war as an officer in the First Kansas Cavalry; he ordered his

|

| Kansas Cavalry Members |

men to prevent southern men from reclaiming fugitive slaves. This action was against the military policy at the time; he was arrested and imprisoned when he refused to countermand the order. D.R. was later permitted to return to active duty, and saw action in Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi and Alabama. He resigned from the army in September 1862.

|

| Merrit Anthony |

The youngest Anthony brother, Merrit, served as a captain in the Union army for the entire duration of the war.

Susan Anthony returned to the family farm in Rochester, New York.

From her diary may be obtained an idea of the busy life which only allowed the briefest entries, but these show her restlessness and dissatisfaction:

"Tried to interest myself in a sewing society; but little intelligence among

|

| Harriet Tubman |

them.... Attended Progressive Friends' meeting; too much namby-pamby-ism.... Went to colored church to hear Douglass. He seems without solid basis. Speaks only popular truths.... Quilted all day, but sewing seems to be no longer my calling.... I stained and varnished the library bookcase today, and superintended the plowing of the orchard.... The last load of hay is in the barn; all in capital order. Fitted out a fugitive slave for Canada with the help of Harriet Tubman.... Washed every window in the house today. Put a quilted petticoat in the frame. Commenced Mrs. Browning's Portuguese Sonnets. .... I wish the government would move quickly, proclaim freedom to every slave and call on every able-bodied negro to enlist in the Union army. How not to do it seems the whole study at Washington. Good, stiff-backed Union Democrats would dare to move; they would have nothing to lose and all to gain for their party. The present incumbents have all to lose; hence dare not avow any policy, but only wait. To forever blot out slavery is the only possible compensation for this merciless war.

. . . While all the women were giving themselves, body and soul, to the great work of the war, the New York Legislature, April 10, 1862, finding them off guard, very quietly amended the law of 1860 and took away from mothers the lately-acquired right to the equal guardianship of their children. They also repealed the law which secured to the widow the control of the property for the care of minor children. Thus at one blow were swept away the results of nearly a decade of hard work on the part of women, and wives and mothers were left in almost the same position as under the old common law. . . . Miss Anthony's anger and sorrow were intense when she heard of the repeal of the laws which she had spent seven long years to obtain, tramping through cold and heat to roll up petitions and traversing the whole State of New York in the dead of winter to create public sentiment in their favor.

This year began the acquaintance with Anna Dickinson, whose letters are as refreshing as a breeze from the ocean:

|

| Anna Dickinson |

"The sunniest of sunny mornings to you, how are you today? Well and happy, I hope. To tell the truth I want to see you very much indeed, to hold your hand in mine, to hear your voice, in a word, I want you--I can't have you? Well, I will at least put down a little fragment of my foolish self and send it to look up at you.... I work closely and happily at my preparations for next winter--no, for the future--nine hours a day, generally; but I never felt better, exercise morning and evening, and never touch book or paper after gaslight this warm weather; so all those talks of yours were not thrown away upon me. What think you of the 'signs of the times?' I am sad always, under all my folly;--this cruel tide of war, sweeping off the fresh, young, brave life to be dashed out utterly or thrown back shattered and ruined! I know we all have been implicated in the 'great wrong,' yet I think the comparatively innocent suffer today more than the guilty. And the result--will the people save the country they love so well, or will the rulers dig the nation's grave? Will you not write to me, please, soon? I want to see a touch of you very much. Very Affectionately Yours Anna E. Dickinson"

Anna Elizabeth Dickinson was well-known abolitionist lecturer. Dickinson was born to Quaker parents in Philadelphia; her father died when she was two years old after giving a speech against slavery. She and her four siblings were raised by her mother. As a 14-year-old, she published a passionate anti-slavery essay in The Liberator. She addressed the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1860. In 1861, she worked as a clerk for the United States Mint, but was fired for criticizing General George McClellan at a public meeting. She became widely known as an eloquent public speaker. During the war she toured the country speaking on the politics of the war and other issues. Dickinson and Susan B. Anthony became close friends; Anthony addressed her in some letters as “Chickie Dickie.”

L&WofSBA:

|

| Lydia Mott |

After speaking at intervals through the summer, she started on a regular tour early in the fall, writing Lydia Mott:

"I can not feel easy in my conscience to be dumb in an hour like this. I am speaking now extempore and more to my satisfaction than ever before. I am amazed at myself, but I could not do it if any of our other speakers were listening to me. I am entirely off old anti-slavery grounds and on the new ones thrown up by the war. What a stay, counsel and comfort you have been to me, dear Lydia, ever since that eventful little temperance meeting in that cold, smoky chapel in 1852. How you have compelled me to feel myself competent to go forward when trembling with doubt and distrust. I never can express the magnitude of my indebtedness to you."

On November 22, 1862 Frederick Douglass had written to fellow abolitionist Theodore Tilton that "Our friend Miss Anthony is at home watching by the bedside of her father who

has been quite ill--but now convalescent." Daniel Anthony died three days later.

She had come home for a few days, and the Sunday morning after election was sitting with her father talking over the political situation. They had been reading the Liberator and the Anti-Slavery Standard and were discussing the probable effect of Lincoln's proclamation, when suddenly he was stricken with acute neuralgia of the stomach. He had not had a day's illness in forty years and had not the slightest premonition of this attack. He lingered in great suffering for two weeks and died on November 25, 1862.

No words can express the terrible bereavement of his family. He had been to them a tower of strength. From childhood his sons and daughters had carried to him every grief and perplexity and there never had been a matter concerning them too trivial to receive his careful attention. . . . He was far ahead of his time in his recognition of the rights of women. Years before he had written to a brother: "Take your family into your confidence and give your wife the purse." He was never willing to enter into any pleasure which his wife did not share. They tell of him that once the daughters persuaded him to remain in town on a stormy evening and go to the Hutchinson concert. As they were driving home he said: "Never again ask me to do such a thing; I suffered more in thinking of your mother at home alone than any enjoyment could possibly compensate."

|

| Lucy Anthony |

A short time before his death he and his wife went to Ontario Beach one afternoon and did not return till 10 o'clock. When asked by the daughters what detained them, the mother answered that they had a fish supper and then strolled on the beach by moonlight; and on their laughing at her and saying she was worse than the girls, she replied: "Your father is more of a lover today than he was the first year of our marriage."

He was a broad, humane, great-hearted man, always mindful of the rights of others, always standing for liberty to every human being. Public-spirited, benevolent and genial in disposition, his loss was widely mourned. The family's devoted friend, Rev. Samuel J. May, conducted the funeral services, at which Frederick Douglass and several prominent Abolitionists paid affectionate tribute, expressing "profound reverence for Mr. Anthony's character as a man, a friend and a citizen."

|

| Abraham Lincoln |

Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, but abolitionists were dissatisfied with it. Anthony was instrumental in forming the Woman's National Loyal League in to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery. The first meeting on May 14, 1863 featured Elizabeth Cady Stanton as its president and Susan B. Anthony as its secretary. In the largest petition drive in the nation's history up to that time, the League collected nearly 400,000 signatures on petitions to abolish slavery and presented them to Congress. The petition drive significantly assisted the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the U.S. The League disbanded in August 1864 after it became clear that the amendment would be approved.

An immense audience, mostly women, assembled in Dr. Cheever's famous church. Miss Anthony called the convention to order . . . Stirring addresses were made by Mrs. Stanton and the veteran anti-slavery speaker, Angelina Grimké Weld, while the Hutchinson family with their songs added inspiration to the occasion. Miss Anthony presented a series of patriotic resolutions with the following spirited address:

"There is great fear expressed on all sides lest this shall be made a war for the negro. I am willing that it shall be. It is a war which was begun to found an empire upon slavery, and shame on us if we do not make it one to establish the freedom of the negro--against whom the whole nation, North and South, East and West, in one mighty conspiracy, has combined from the beginning. Instead of suppressing the real cause of the war, it should have been proclaimed not only by the people but by the President, Congress, Cabinet and every military commander. Instead of President Lincoln's waiting two long years before calling to the aid of the government the millions of allies whom we have had within the territory of rebeldom, it should have been the first decree he sent forth. . . . Every interest of the insurgents, every dollar of their property, every institution, every life in every rebel State even, if necessary, should have been sacrificed, before one dollar or one man should have been drawn from the free States. How much more then was it the President's duty to confer freedom on the millions of slaves, transform them into an army for the Union, cripple the rebellion and establish justice, the only sure foundation of peace.

"I therefore hail the day when the government shall recognize that this is a war for freedom. We talk about returning to 'the Union as it was' and 'the Constitution as it is'--about "restoring our country to peace and prosperity--to the blessed conditions which existed before the war!" I ask you what sort of peace, what sort of prosperity, have we had? Since the first slave ship sailed up the James river with its human cargo and there, on the soil of the Old Dominion, it was sold to the highest bidder, we have had nothing but war. . . . Between the slave and the master there has been war, and war only. This is but a new form of it.

"No, no; we ask for no return to the old conditions. We ask for something better. We want a Union which is a Union in fact, a Union in spirit, not a sham. . . .

"Woman must now assume her God-given responsibilities and make herself what she is clearly designed to be, the educator of the race. Let her no longer be the mere reflector, the echo of the worldly pride and ambition of man. Had the women of the North studied to know and to teach their sons the law of justice to the black man, they would not now be called upon to offer the loved of their households to the bloody Moloch of war."

|

| Lucy Stone |

. . . The fourth resolution, asking equal rights for women as well as negroes, was seriously objected to by several who insisted that they did not want political rights. Lucy Stone, Mrs. Weld, Mrs. Rose and Mrs. Coleman made strong speeches in its favor, and Miss Anthony said: "This resolution merely makes the assertion that in a genuine republic, every citizen must have the right of representation. You remember the maxim 'Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.' This is the fundamental principle of democracy, and before our government can be placed on a lasting foundation, the civil and political rights of every citizen must be practically established. This is the meaning of the resolution. . . . This is the question before us: Is it possible that peace and union shall be established in this country, is it possible for this government to be a true democracy, a genuine republic, while one-sixth or one-half of the people are disfranchised?"

. . .Soon after closing the league headquarters, Miss Anthony went to Auburn to attend the wedding of Wm. Lloyd Garrison, Jr., and Ellen, daughter of her dear friend Martha C. Wright and niece of Lucretia Mott, a union of two families very acceptable to the friends of both.

From this scene of festivity she returned home to meet a fresh sorrow in the sudden death, almost at the hour of her arrival, of Ann Eliza, daughter of her eldest sister Guelma and Aaron McLean, the best beloved of all her nieces. She was twenty-three years old, beautiful and talented, a good musician and an artist of fine promise. In her Miss Anthony had centered many hopes and ambitions, and the letters show that she was always planning and working for her future as she would have done for that of a cherished daughter. She was laid to rest on the silver wedding anniversary of her parents. Miss Anthony writes: "She had ceased to be a child and had become the full grown woman, my companion and friend. I loved her merry laugh, her bright, joyous presence, and yet my loss is so small compared to the awful void in her mother's life that I scarcely dare mention it." Months afterwards she wrote her sister Hannah:

"Today I made a pilgrimage to Mount Hope. The last rays of red, gold and

purple fringed the horizon and shone serenely on the mounds above our dear father and Ann Eliza. What a contrast in my feelings; for the one a subdued sorrow at the sudden ending of a life full-ripened, only that we would have basked in its sunshine a little longer; for the other a keen anguish over the untimely cutting off in the dawn of existence, with the hopes and longings but just beginning to take form, the real purpose of life yet dimly developed, a great nature but half revealed. The faith that she and all our loved and gone are graduated into a higher school of growth and progress is the only consolation for death."

At another time she wrote her brother: "This new and sorrowful reminder of the brittleness of life's threads should soften all our expressions to each other in our home circles and open our lips to speak only words of tenderness and approbation. We are so wont to utter criticisms and to keep silence about the things we approve. I wish we might be as faithful in expressing our likes as our dislikes, and not leave our loved ones to take it for granted that their good acts are noted and appreciated and vastly outnumber those we criticise. The sum of home happiness would be greatly multiplied if all families would conscientiously follow this method."

There were urgent appeals in these days from the lately-married brother and his wife for sister Susan to come to Kansas and, as no public work seemed to be pressing, she started the latter part of January, 1865. She stopped in Chicago to visit her uncle Albert Dickinson, was detained a week by heavy storms, and reached Leavenworth the last day of the month. . . . Her brother was renominated for mayor and plunged at once into the thick of a political campaign, while Miss Anthony went to the office to help manage his newspaper, limited only by his injunction "not to have it all woman's rights and negro suffrage."

The labor, however, which she most enjoyed was among the colored refugees. Soon after the slaves were set free they flocked to Kansas in large numbers, and what should be done with this great body of uneducated, untrained and irresponsible people was a perplexing question. She went into the day schools,

.png) |

| Hiram Revels Rhodes |

Sunday-schools, charitable societies and all organizations for their relief and improvement. The journal shows that four or five days or evenings every week were given to this work and that she formed an equal rights league among them. A colored printer was put into the composing-room, and at once the entire force went on strike. The diary declares "it is a burning, blistering shame," and relates her attempts to secure other work for him. She met at this time Hiram Revels, a colored Methodist preacher, afterwards United States senator from Mississippi.

. . . Mrs. Stanton insisted that she should not remain buried in Kansas and concluded a long letter:

"I hope in a short time to be comfortably located in a new house where we will have a room ready for you when you come East. I long to put my arms around you once more and hear you scold me for my sins and short-comings. Your abuse is sweeter to me than anybody else's praise for, in spite of your severity, your faith and confidence shine through all. O, Susan, you are very dear to me. I should miss you more than any other living being from this earth. You are intertwined with much of my happy and eventful past, and all my future plans are based on you as a coadjutor. Yes, our work is one, we are one in aim and sympathy and we should be together. Come home."

. . . The threatened division in the Abolitionist ranks and the reported

determination of Mr. Garrison to disband the Anti-Slavery Society, filled her with dismay and she sent back the strongest protests she could put into words:

"How can any one hold that Congress has no right to demand negro suffrage in the returning rebel States because it is not already established in all the loyal ones? What would have been said of Abolitionists ten or twenty years ago, had they preached to the people that Congress had no right to vote against admitting a new State with slavery, because it was not already abolished in all the old States? It is perfectly astounding, this seeming eagerness of so many of our old friends to cover up and apologize for the glaring hate toward the equal recognition of the manhood of the black race."

|

| Wendell Phillips |

. . . A letter from Mr. Phillips said: "Thank you for your kind note. I see you understand the lay of the land and no words are necessary between you and me. Your points we have talked over. If Garrison should resign, we incline to Purvis for president for many, many reasons." All the letters received by Miss Anthony during May and June were filled with the story of the dissension in the Anti-Slavery Society.

. . . Those most intimately connected with Miss Anthony sustained the position of Mr. Phillips--Mrs. Stanton, Parker Pillsbury, Robert Purvis, Charles Remond, Stephen Foster, Lucretia and Lydia Mott, Anna Dickinson, Sarah Pugh--and she herself was his staunchest defender. Believing as strongly as she did that the suffrage is the very foundation of liberty, that without it there can be no real freedom for either man or woman, she could not have done otherwise, and yet, so great was her reverence and affection for Mr. Garrison, it was with the keenest regret she found herself no longer able to follow him. She writes: "I am glad I was spared from witnessing that closing scene. It will be hard beyond expression to leave him out of our councils, but he never will be out of our sympathies. I hope you will refrain from all personalities. Pro-slavery signs are too apparent and too dangerous at this hour for us to stop for personal adjustments. To go forward with the great work pressing upon the society, without turning to the right or the left, is the one wise course."

|

| Robert Purvis |

Robert Purvis was a prominent African-American abolitionist; although born in Charleston, South Carolina, he had lived most of his life in Philadelphia. Of mixed race, Purvis and his brothers chose to identify with the black community and use their education and wealth to support the abolition of slavery, as well as projects in education to help the advance of African Americans.

In January 1865, the House of Representatives passed 13th amendment in January.

|

| Pages from Anthony's diary |

Anthony stayed with her brother, D.R. Anthony, in Leavenworth Kansas for eight months in 1865 to assist with his newspaper. She also helped with organizing freedman's relief in the state. In April, Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate forces at Appomattox, Virginia; a few days later, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in Washington, D.C. At a memorial

|

| Abraham Lincoln |

gathering in Leavenworth, Susan Anthony was one of the speakers:

"I was reading the President's last speech when the stunning telegram of his assassination reached me. . . . My soul was sad and sick at what seemed his settled purpose - to consign the ex-slaves back to the tender mercies of the disappointed, desperate, sullen revengeful ex-lords of the lash . . . re-arming our enemies with the ballot, the mightiest weapon for good or evil . . . disarming and disfranchsing our loyal black soldiers - men to whom our nation is largely, if not altogether, indebted for its triumphs in the field over the rebellion . . .To me it looked like the crimes of crimes . . .

"God's one great purpose, is that this nation shall establish and practice his law of the perfectly equal humanity of all races, nations and colors. "

Miss Anthony was seated in her brother's office reading the papers when she learned to her amazement that several resolutions had been offered in the House of Representatives sanctioning disfranchisement on account of sex. Up to this time the Constitution of the United States never had been desecrated by the word "male," and she saw instantly that such action would create a more formidable barrier than any now existing against the enfranchisement of women. She hesitated no longer but started immediately on her homeward journey . . .

This was the first demand ever made for Congressional action on this question.

|

| Thaddeus Stevens |

The Fourteenth Amendment, as proposed, contained in Section 2, to which the women objected, the word "male" three times . . .If it had been adopted without this word "male," all women would have been virtually enfranchised, as men would have let women vote rather than have them counted out of the basis of representation. Thaddeus Stevens made a vigorous attempt to have women included in the provisions of this amendment.

. . . She went to Philadelphia to visit James and Lucretia Mott and interest

|

| Loyal League Petition |

Mary Grew and Sarah Pugh and all the friends in that locality; then back to New York with tireless energy and unflagging zeal. She wrote articles for the Anti-Slavery Standard, sent out petitions and left no stone unturned to accomplish her purpose. The diary shows the days to have been well filled:

"Went to Tilton's office to express regrets at not being able to attend their tin wedding. He read us his editorial on Seward and Beecher. Splendid!... Went to hear Beecher, morning and evening. There is no one like him.... Spent the day at Mrs. Tilton's and went with her to Mrs. Bowen's....Excellent audience in Friends' meeting house, at Milton-on-the-Hudson. . . . Went over to New Jersey to confer with Lucy Stone and Antoinette Blackwell.... Called at Dr. Cheever's, and also had an interview with Robert Dale Owen.... Went to Worcester to see Abby Kelly Foster and from there to Boston.... Took dinner at Garrison's. Saw Whipple and May, then went to Wendell Phillips'.... Returned to New York and commenced work in earnest. Spent nearly all the Christmas holidays addressing and sending off petitions."

Henry Ward Beecher and Theodore Tilton entered heartily into the plans of

|

| Henry Ward Beecher |

Miss Anthony and Mrs. Stanton. Mr. Tilton proposed that they should form a National Equal Rights Association, demanding suffrage for negroes and for women, that Mr. Phillips should be its president, the Anti-Slavery Standard its official organ; and Mr. Beecher agreed to lecture in behalf of this new movement. Mr. Tilton came out with a strong editorial in the Independent, advocating suffrage for women and paying a beautiful tribute to the efficient services in the past of those who were now demanding recognition of their political rights

Susan Anthony headed back east after she learned that an amendment to the U.S. Constitution had been proposed that would provide citizenship for African Americans but would also for the first time introduce the word "male" into the constitution. Anthony supported citizenship for blacks but opposed any attempt to link it with a reduction in the status of women. Her ally Stanton agreed, saying "if that word 'male' be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out." Both Stanton and Anthony broke with their abolitionist backgrounds and lobbied strongly against ratification of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, which granted African American men citizenship and the right to vote.

The Fourteenth Amendment explicitly designated voters as "male citizens." For the first time, the United States Constitution included a sexual distinction. Both Stanton and Anthony were angry that the abolitionists, their former partners in working for both African American and women's rights, refused to demand that the language of the amendments be changed.

Founded on May 10, 1866, during the Eleventh National Woman’s Rights Convention, the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) elected Lucretia Mott as president and created an executive committee that included Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucy Stone. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex."

Robert Purvis, one of the most elegant and scholarly colored men our country

|

| Robert Purvis |

has known . . sent this noble response:

"I can not agree that this or any hour is 'especially the negro's.' I am an anti-slavery man because I hate tyranny and in my nature revolt against oppression, whatever its form or character. As an Abolitionist, therefore, I am for the equal rights movement, and as one of the confessedly oppressed race, how could I be otherwise? With what grace could I ask the women of this country to labor for my enfranchisement, and at the same time be unwilling to put forth a hand to remove the tyranny, in some respects greater, to which they are subjected? Again wishing you a successful meeting, I am very gratefully yours."

. . . The Woman's Rights Convention met in Dr. Cheever's church, May 10, 1866, with a large audience present. It was their first meeting since before the war, and while it had many elements of gladness, yet it was not unmixed with sorrow. Mr. Garrison was absent, the first rift had been made in the love and gratitude in which for many years Mr. Phillips had been held, and a vague feeling of distrust and alarm was beginning to creep over the women, lest, after all these years of patient work, they were again to be sacrificed. . .

|

| Wendell Phillips |

A short time thereafter Miss Anthony, Mrs. Stanton, Mr. Phillips and Mr. Tilton were in the Standard office discussing the work. Mr. Phillips argued that the time was ripe for striking the word "white" out of the New York constitution, at its coming convention, but not for striking out "male." Mr. Tilton supported him, in direct contradiction to all he had so warmly advocated only a few weeks before, and said what the women should do was to canvass the State with speeches and petitions for the enfranchisement of the negro, leaving that of the women to come afterward, presumably twenty years later, when there would be another revision of the constitution. Mrs. Stanton, entirely overcome by the eloquence of these two gifted men, acquiesced in all they said; but Miss Anthony, who never could be swerved from her standard by any sophistry or blandishments, was highly indignant and declared that she would sooner cut off her right hand than ask the ballot for the black man and not for woman.

. . . For the purpose of arousing public interest in the approaching New York

|

| Frederick Douglass |

Constitutional Convention, an equal rights meeting was held at Albany, in Tweddle Hall, November 21. To make this a success Miss Anthony spent many weeks of hard work. . . . At this Albany convention political differences began to appear. Mrs. Stanton complimented the Democrats for the assistance they had rendered; Frederick Douglass objected to their receiving any credit, branding their advocacy as a trick of the enemy, and there were frequent sharp encounters. . . . A form of petition was approved asking that women might be members of the coming Constitutional Convention and vote on the new constitution. Respectful reports were made by the New York papers with the exception of the World, which said in a long and abusive article:

"Altogether the ablest, most dignified and best-balanced man in the body is Frederick Douglass, and there is a deep feeling for him for United States senator in spite of the drift of the convention, which is evidently in favor of Susan B. Anthony; notwithstanding which Elizabeth Cady Stanton is likewise a candidate with considerable strength, favoring as she does the Copperheads, the Democratic party and other dead and buried remains of alleged disloyalty.

"Susan is lean, cadaverous and intellectual, with the proportions of a file and the voice of a hurdy-gurdy. She is the favorite of the convention. Mrs. Stanton is of intellectual stock, impressive in manner and disposed to henpeck the convention which of course calls out resistance and much cackling.... Susan has a controlling advantage over her in the fact that she is unencumbered with a husband. As male members of Congress rarely have wives in Washington, so female members will be expected to be without husbands at the capital....

"Parker Pillsbury, one of the notabilities of the body, is a good-looking white

|

| Parker Pillsbury |

man naturally, but has a cowed and sneakish expression stealing over him, as though he regretted he had not been born a nigger or one of these females.... Lucy Stone, the president of the convention, is what the law terms a 'spinster.' She is a sad old girl, presides with timidity and hesitation, is wheezy and nasal in her pronunciation and wholly without dignity or command.... Mummified and fossilated females, void of domestic duties, habits and natural affections; crack-brained, rheumatic, dyspeptic, henpecked men, vainly striving to achieve the liberty of opening their heads in presence of their wives; self-educated, oily-faced, insolent, gabbling negroes, and Theodore Tilton, make up the less than a hundred members of this caravan, called, by themselves, the American Equal Rights Association."

. . . In November Miss Anthony went to a great anti-slavery meeting in Philadelphia. Between the two sessions, Lucretia Mott invited about twenty of the leading men and women to lunch with her. At her request Miss Anthony acted as spokesman and, in behalf of the women, begged Mr. Phillips to reconsider his position and make the woman's and the negro's cause identical, but here, in the presence of the women who had stood shoulder to shoulder with him in all his hard-fought battles of the last twenty years, he again refused, declaring that their time had not yet come. Miss Anthony sent the most impassioned appeals to the Joint Committee of Fifteen, with Thaddeus Stevens as chairman, which had charge of the congressional policy on reconstruction, urging that if they could not report favorably on the petitions, at least they would not interpose any new barrier against woman's right to the ballot; but, although Mr. Stevens had ever been friendly to the claims of women, he refused to recognize them now. . . .

This letter from Lucretia Mott shows that some men remained true to the woman's cause: "My husband and myself cordially hail this movement. The negro's hour came with his emancipation from cruel bondage. He now has advocates not a few for his right to the ballot. Intelligent as these are, they must see that this right can not be consistently withheld from women. We pledge $50 toward the necessary funds."

. . . In her diary Antony writes: "Even Charles Sumner bends to the spirit of

|

| Charles Sumner |

compromise and presents a constitutional amendment which concedes the right to disfranchise law-abiding, tax-paying citizens."

Robert Purvis again expressed his cordial sympathy: "I am heartily with you in the view 'that the reconstruction of the Union is a work of greater importance than the restoration of the rebel States;' and that it should be in accordance with the true republican idea of the personal rights of all our citizens, without regard to sex or color. If the settlement of this question upon the comprehensive basis of equal rights and impartial justice to all should require the postponement of the enfranchisement of the colored man, I am willing for the delay, though it should take a decade of years to 'fight it out on that line.'" Mr. Purvis frequently said in the debates of those days that he would rather his son never should be enfranchised than that his daughter never should be, as she bore the double disability of sex and color and, by every principle of justice, should be the first to be protected.

|

| George Francis Train |

The following year, the organization became active in Kansas where black suffrage and woman suffrage were to be decided by popular vote. Henry Blackwell and Kansas Senator Samuel Wood invited George Francis Train to campaign in Kansas; they hoped that Train, a Democratic, would attract more of the Democratic voters. Lucretia Mott was horrified at the alliance of Stanton and Anthony with Train. In a letter to her sister, Martha, she said that she did not intend to subscribe to their newspaper, The Revolution. She was concerned that Train's racism was a bad influence on Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In November, she wrote in a letter:

New York, 11th mo. 12th, 1866. . . . Patty went with me yesterday to Elizabeth Stanton's to lunch, Lucy Stone and S. B. Anthony meeting us there; the time all taken up in discussing the coming convention . . . Elizabeth was like herself, full of spirits, and so pleasant. . . This Equal Rights movement is no play — but I cannot enter into it! Just hearing their talk and the reading made me ache all over, and glad to come away and lie on the sofa here to rest . . . Tomorrow we lunch at Sarah Hicks', and then come back to company to tea; something all the time. On First-day I dined at Hannah Haydock's after Fifteenth st. meeting; found S. B. Anthony waiting for me to go somewhere in a carriage with her to meet Horace Greeley and an Hon. Mr. Griffing. I just couldn't do it. Moreover, Susan and some others wanted me to go hear Beecher and have him talk with us afterwards, preparatory to his speech in Albany, — but I couldn't do that any more than the other! There is no rest !

. . . I was wondering, the other day, what use the increasing number of churches would be put to, as civilization outgrew them.

|

| Lucy Stone |

The AERA's Kansas campaign began when Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell arrived in April 1867. The AERA workers were disconcerted when, after an internal struggle, Kansas Republicans decided to support suffrage for black men only, not merely refusing to support women's suffrage but forming an "Anti Female Suffrage Committee" to organize opposition to those who were campaigning for it. In a letter to Anthony, Stone wrote,

The negroes are all against us. There has just now left us an ignorant black preacher named Twine, who is very confident that women ought not to vote. These men ought not to be allowed to vote before we do, because they will be just so much more dead weight to lift.

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton arrived in September to work on the campaign. They created a storm of controversy by accepting help from George Francis Train, the wealthy businessman and flamboyant speaker who supported women's rights. By 1867 he was promoting himself as an independent candidate for president. Train was also a racist who openly disparaged the integrity and intelligence of African Americans, supporting women's suffrage partly in the belief that the votes of women would help contain the political power of blacks.

The hardships of a campaign in the early days of Kansas scarcely can be described. Much of the travelling had to be done in wagons, fording streams, crossing the treeless prairies, losing the faintly outlined road in the darkness of night, sleeping in cabins, drinking poor water and subsisting on bacon, soda-raised bread, canned meats and vegetables, dried fruits and coffee without cream or milk, sweetened with sorghum. The nights offered the greatest trial, owing to a species of insect supposed to breed in the cotton wood trees. In one of her letters home Miss Anthony says:

"It is now 10 A. M. and Mrs. Stanton is trying to sleep, as we have not slept a wink for several nights, but even in broad daylight our tormentors are so active that it is impossible. We find them in our bonnets, and this morning I think we picked a thousand out of the ruffles of our dresses. I can assure you that my avoirdupois is being rapidly reduced. It is a nightly battle with the infernals.... Twenty-five years hence it will be delightful to live in this beautiful State, but now, alas, its women especially see hard times, and there is no poetry in their lives. . . . It is enough to exhaust the patience of Job, the slip-shod way in which telegraph, express and post offices are managed here. It is almost impossible to arrange for halls or to get literature delivered at the point where it is sent. We speak in school houses, barns, sawmills, log cabins with boards for seats and lanterns hung around for lights, but people come twenty miles to hear us. The opposition follow close upon our track, but they make converts for us. The fact is that most of them are notoriously wanting in right action toward women. Their objections are as low and scurrilous as they used to be in the East fifteen or twenty years ago. There is a perfect greed for our tracts, and the friends say they do more missionary work than we ourselves. If our suffrage advocates only would go into the new settlements at the very beginning, they could mould public sentiment, but they wait until the comforts of life are attainable and then find the ground occupied by the enemy.

. . . A striking instance of the first reception usually accorded the two ladies is given by Mrs. Starrett, in her Kansas chapter in the History of Woman Suffrage:

"All were prepared beforehand to do Mrs. Stanton homage for her talents and fame, but many persons who had formed their ideas of Miss Anthony from the unfriendly remarks in opposition papers had conceived a prejudice against her. Perhaps I can not better illustrate how she everywhere overcame and dispelled this prejudice than by relating my own experience. A convention was called at Lawrence, and the friends of woman suffrage were asked to entertain strangers who might come from abroad. Ex-Governor Robinson asked me to entertain Mrs. Stanton. We had all things in readiness when I received a note stating that she had found relatives in town with whom she would stop, and Miss Anthony would come instead. I hastily put on bonnet and shawl, saying, 'I won't have her and I am going to tell Governor Robinson so.' At the gate I met a dignified Quaker-looking lady with a small satchel and a black and white shawl on her arm. Offering her hand she said, 'I am Miss Anthony, and I have been sent to you for entertainment during the convention.'... Half disarmed by her genial manner and frank, kindly face, I led the way into the house and said I would have her stay to tea and then we would see what farther arrangements could be made. While I was looking after things she gained the affections of the babies; and seeing the door of my sister's sick-room open, she went in and in a short time had so won the heart and soothed instead of exciting the nervous sufferer, entertaining her with accounts of the outside world, that by the time tea was over I was ready to do anything if Miss Anthony would only stay with us. And stay she did for over six weeks, and we parted from her as from a beloved and helpful friend. I found afterwards that in the same way she made the most ardent friends wherever she became personally known."

. . . The Hutchinsons--John, his son Henry and lovely daughter Viola--were giving a series of concerts, travelling in a handsome carriage drawn by a span of white horses. As they had one vacant seat, they were carrying Rev.

|

| Olympia Brown |

Olympia Brown, a talented Universalist minister from Massachusetts, who had been canvassing the State for several months, and she spoke for suffrage while they sang for both the negro and woman.

. . . On the 7th of October came a telegram from George Francis Train, who was then at Omaha, largely interested in the Union Pacific railroad. He had been invited by the secretary and other members of the St. Louis Suffrage Association to go to Kansas and help in the woman's campaign. Accordingly he telegraphed that if the committee wanted him he was ready, would pay his own expenses and win every Democratic vote. Miss Anthony never had seen Mr. Train; she merely knew of him as very wealthy and eccentric. . . .

On election day the Hutchinsons, Miss Anthony and Mrs. Stanton, in open carriages, visited all the polling-places in Leavenworth, where the two ladies spoke and the Hutchinsons sang. Both amendments were overwhelmingly defeated, that for negro suffrage receiving 10,843 votes, and that for woman suffrage 9,070, out of a total of about 30,000. These 9,000 votes were the first ever cast in the United States for the enfranchisement of women. How many of them were Republican and how many Democratic, and how much influence Mr. Train may have had one way or another, never can be known; but it is a significant fact that Douglas county, the most radical Republican district, gave the largest vote against woman suffrage, and Leavenworth, the strongest Democratic county, gave the largest majority in its favor.

The willingness of Anthony and Stanton to work with Train alienated many AERA members and other reform activists. Stone said she considered Train to be "a lunatic, wild and ranting." Anthony and Stanton angered Stone by including her name, without her permission, in a public letter praising Train. Stone and her allies angered Anthony by charging her with misuse of funds, a charge that was later disproved, and by blocking payment of her salary and expenses for her work in Kansas.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote in a letter:

If George Francis Train had done for the negro all that he has done for woman . . . the Abolitionists would enshrine him as a saint. The attacks on Susan and me by a few persons have been petty and narrow, but we are right and this nine days' wonder will soon settle itself. . . . We have reason to congratulate

ourselves that we have shocked more friends of the cause into life . . . People who never gave a cent or said a word for our movement are the most concerned lest Susan and I should injure it. Mr. Train has some extravagances and idiosyncrasies, but he is willing to devote his energies to our cause when no other man is, and we should be foolish not to accept his aid.

The History of Woman Suffrage stated the conclusions drawn by the wing of the movement associated with Anthony and Stanton:

Our liberal men counseled us to silence during the war, and we were silent on our own wrongs; they counseled us again to silence in Kansas and New York, lest we should defeat 'negro suffrage,' and threatened if we were not, we might fight the battle alone. We chose the latter, and were defeated. But standing alone we learned our power... woman must lead the way to her own enfranchisement.

The AERA held its first annual meeting in New York City on May 9, 1867. Asked by George Downing, an African American, whether she would be willing for the black man to have the vote before woman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton replied,

I would say, no; I would not trust him with all my rights; degraded, oppressed himself, he would be more despotic with the governing power than even our Saxon rulers are. I desire that we go into the kingdom together.

Sojourner Truth, a former slave, said that, "if colored men get their rights, and not colored

|

| Sojourner Truth |

women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before." She gave a speech at the meeting:

My friends, I am rejoiced that you are glad, but I don't know how you will feel when I get through. I come from another field-the country of the slave. They have got their liberty-so much good luck to have slavery partly destroyed; not entirely. I want it root and branch destroyed. Then we will all be free indeed.

I feel that if I have to answer for the deeds done in my body just as much as a man, I have a right to have just as much as a man. There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.

So I am for keeping the thing going while things are stirring; because if we wait till it is still, it will take a great while to got it going again. White women are a great deal smarter, and know more than colored women, while colored women do not know scarcely anything. They go out washing, which is about as high as a colored woman gets, and their men go about idle, strutting up and down; and when the women come home, they ask for their money and take it all, and then scold because there is no food. I want you to consider on that, chil'n I call you chil'n; you are somebody's chil'n and I am old enough to be mother of all that is here.

I want women to have their rights. In the courts women have no right, no voice; nobody speaks for them. . . . If it is not a fit place for women, it is unfit for men to be there.

I am above eighty years old; it is about time for me to be going. I have been forty years a slave and forty years free, and would be here forty years more to have equal rights for all. I suppose I am kept here because something remains for me to do, I suppose I am yet to help to break the chain. I have done a great deal of work; as much as a man, but did not get so much pay. I used to work in the field and bind grain, keeping up with the cradler; but men doing no more, got twice as much pay; so with the German women. They work in the field and do as much work, but do not got the pay. We do as much, we eat as much, we want as much.

. . . I want to keep the thing stirring, now that the ice is cracked. What we want is a little money. You men know that you get as much again as women when you write, or for what you do. When we get our rights we shall not have to come to you for money, for then we shall have money enough in our own pockets; and may be you will ask us for money. . . . When we have got this battle once fought we shall not be coming to you any more.

You have been having our rights so long, that you think, like a slave-holder, that you own us. I know that it is hard for one who has held the reins for so long to give up; it cuts like a knife. It will feel all the better when it closes up again.

. . . Now I will do a little singing. I have not heard any singing since I came here.

Accordingly, suiting the action to the word, Sojourner sang, "We are going home." "There, children," said she, "in heaven we shall rest from all our labors; first do all we have to do here. There I am determined to go, not to stop short of that beautiful place, and I do not mean to stop till I get there, and meet you there, too."

Others disagreed: Abby Kelley Foster said that suffrage for black men was a more pressing issue than suffrage for women. Henry Ward Beecher said he was in favor of universal suffrage, but believed that by demanding the vote for both blacks and women, the movement was likely to achieve at least a partial victory by winning the vote for black men.

According to the notes of the convention, there were debates on Friday morning, May 10:

GEORGE T. DOWNING wished to know whether he had rightly understood

|

| George Downing |

that Mrs. Stanton and Mrs. Mott were opposed to the enfranchisement of the colored man, unless the ballot should also be accorded to woman at the same time.

Mrs. STANTON said: All history proves that despotisms, whether of one man or millions, can not stand, and there is no use of wasting centuries of men and means in trying that experiment again. Hence I have no faith or interest in any reconstruction on that old basis. To say that politicians always do one thing at a time is no reason why philosophers should not enunciate the broad principles that underlie that one thing and a dozen others. We do not take the right step for this hour in demanding suffrage for any class; as a matter of principle I claim it for all. But in a narrow view of the question as a matter of feeling between classes, when Mr. Downing puts the question to me, are you willing to have the colored man enfranchised before the woman, I say, no; I would not trust him with all my rights; degraded, oppressed himself, he would be more despotic with the governing power than even our Saxon rulers are. I desire that we go into the kingdom together, for individual and national safety demand that not another man be enfranchised without the woman by his side.

. . . CHARLES L. REMOND said that if he were to lose sight of expediency, he must side with Mrs. Stanton, although to do so was extremely trying; for he could not conceive of a more unhappy position than that occupied by millions of American men bearing the name of freedmen while the rights and privileges of free men are still denied them.

|

| Elizabeth Cady Stanton |

Mrs. STANTON said: That is equaled only by the condition of the women by their side. There is a depth of degradation known to the slave -women that man can never feel. To give the ballot to the black man is no security to the woman. Saxon men have the ballot, yet look at their women, crowded into a few half-paid employments. Look at the starving, degraded class in our 10, 000 dens of infamy and vice if you would know how wisely and generously man legislates for woman.

. . . Miss ANTHONY said -- The question is not, is this or that person right, but what are the principles under discussion. As I understand the difference between Abolitionists, some think this is harvest time for the black man, and seed-sowing time for woman.

Others, with whom I agree, think we have been sowing the seed of individual rights, the foundation idea of a republic for the last century, and that this is the harvest time for all citizens who pay taxes, obey the laws and are loyal to the government. (Applause.)

Mr. REMOND said : In an hour like this I repudiate the idea of expediency. All I ask for myself I claim for my wife and sister, Let our action be based upon the rock of everlasting principle. No class of citizens in this country can be deprived of the ballot without injuring every other class. I see how equality of suffrage in the State of New York is necessary to maintain emancipation in South Carolina. Do not moral principles, like water, seek a common level ? Slavery in the Southern States crushed the right of free speech in Massachusetts and made slaves of Saxon men and women, just as the $250 qualification in the Constitution of this State degrades and enslaves black men all over the Union.

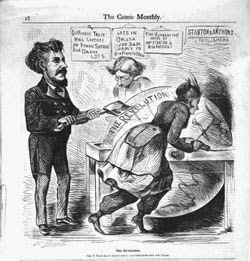

On January 8, 1868, Anthony first published the women's rights weekly journal, The Revolution. George Francis Train provided $600 in start-up funding. Printed in New York City, the paper's motto was:

"The true republic—men, their rights and nothing more; women, their rights and nothing less."

Anthony worked as the publisher and business manager, while Elizabeth Cady Stanton acted

as editor. The main thrust of The Revolution was to promote women’s and African-Americans’ right to suffrage, but it also discussed issues of equal pay for equal work, more liberal divorce laws and the church’s position on women’s issues. Controversy over Train's involvement continued; in an early issue of The Revolution, Anthony printed a letter from William Lloyd Garrison:

January 4th [1868]

Dear Miss Anthony:

In all friendliness, and with the highest regard for the Woman's Rights movement, I cannot refrain from expressing my regret and astonishment that you and Mrs. Stanton should have taken such leave of good sense, and departed so far from true self respect, as to be travelling companions and associate lecturers with that crack-brained harlequin and semi-lunatic, George Francis Train!

. . . You will only subject yourselves to merited ridicule and condemnation, and turn the movement which you aim to promote into unnecessary contempt. . .

The colored people and their advocates have not a more abusive assailant before him, to whom he delights to ring the changes upon the 'nigger,' 'nigger’ ad nauseam. He is as destitute of principle as he is of sense, and is fast gravitating toward a lunatic asylum. He may be of use in drawing an audience; but so would a kangaroo, a gorilla, or a hippopotamus.

It seems you are looking to the Democratic party, and not to the Republican, to give success politically to your movement! I should as soon think of looking to the Great Adversary to espouse the cause of righteousness. The Democratic party is the 'anti nigger' party, and composed of all that is vile and brutal on the land with very little that is decent and commendable.

|

| Thomas Higginson |

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote to Thomas W. Higginson:

New York, Jan 13 1868

Mr Higginson Dear Friend,

Our "pathway" is straight to the ballot box, with no variableness nor shadow of turning. I know we have shocked our old friends who were half asleep on the woman question into a new life, just waking from slumber they are cross, can't see clearly where we are going, but time will show that Miss Anthony & myself are neither idiots or lunatics . . . We do care what all good men like you say, but just now the men that will do something to help us are more important. . . . You know the "white male" is the aristocracy of this county, we belong to the peasantry, the ruling class never did see the wrongs of the oppressed under its own heel. My cousin Gerrit Smith always laughs when I say to him that he

|

| Gerrit Smith |

believes in equality on a southern plantation, but not in his own home! The position of men as Garrison, Phillips, Sumner in their treatment of our question today proves that we must not trust any of you. All these men who have pushed us aside for years saying "this is the negro's hour" now when we turn from them & find help in other quarters, turn up the white of their eyes! & cry out the cause

. . . Do they ignore everyone who is false to women? by no means. - Why ask us to ignore everyone who is false to the negro . . . We are right in our present position. We demand suffrage for all the citizens of the republic . . . I would not talk of negroes or women, but citizens . . .

Stanton wrote in her memoirs:

George Francis Train was then in his prime–a large, fine-looking man, a gentleman in dress and manner, neither smoking, chewing, drinking, nor gormandizing. He was an effective speaker and actor . . . To be sure our friends, on all sides, fell off, and those especially who wished us to be silent on the question of woman's rights, declared "the cause too sacred to be advocated by such a charlatan as George Francis Train." We thought otherwise . . . Mr. Train made it possible for us to establish a newspaper, which gave another impetus to our movement. The Revolution, published by Susan B. Anthony and edited by Parker Pillsbury and myself, lived two years and a half and was then consolidated with the New York Christian Enquirer, edited by the Rev. Henry Bellows, D. D. I regard the brief period in which I edited the Revolution as one of the happiest of my life, and I may add the most useful. . . . We said at all times and on all other subjects just what we thought, and advertised nothing that we did not believe in. No advertisements of quack remedies appeared in our columns. . . . One day, when a man blustered in. . . . On leaving, with prophetic vision, he said, "I prophesy a short life for this paper; the business world is based on quackery, and you cannot live without it." With melancholy certainty, I replied, "I fear you are right.

On the very day the first copy of The Revolution appeared, Mr. Train announced that he was going to England immediately. Miss Anthony wrote in her diary:

"My heart sank within me; only our first number issued and our strongest helper and inspirer to leave us! This is but another discipline to teach us that we must stand on our own feet."

Mr. Train gave her $600 and assured her that he had arranged with Mr.

|

| George Francis Train |

Melliss to supply all necessary funds during his short absence, but she felt herself invested with a heavy responsibility. . . . Instead of Mr. Train's securing writers and subscribers in Europe, he was arrested for complicity with the Fenians the moment he made his first speech, and spent the year in a Dublin jail. He wrote that the finding of fifty copies of The Revolution in his possession was an additional reason for his arrest, as the officials did not stop to read a word, the name was sufficient. While Mr. Train continued his contributions to the paper during his residence in jail, he was not able to meet his financial obligations to it. . . .Miss Anthony was used to such care. She had been the financial burden-bearer of every reform with which she had been connected, but to this crushing weight was added such a persecution as she never had experienced before, even in the days of pro-slavery mobs. Then the attacks had been made by open and avowed enemies, and she had had a host of staunch supporters to share them and give her courage; now her persecutors were in ambush and were those who had been her nearest and dearest friends; and now she was alone except for Mrs. Stanton and Mr. Pillsbury. . . . The excuse for this persecution was that the Equal Rights Association was injured by the publication of The Revolution.

The following graphic description, by the correspondent, Nellie Hutchinson, was published in the Cincinnati Commercial:

|

| The Revolution's office at the far right |

There's a peculiarly resplendent sign at the head of the third flight of stairs, and obeying its directions I march into the north corridor and enter The Revolution office. Nothing so very terrible after all. The first face that salutes my vision is a youthful one--fresh, smiling, bright-eyed, auburn-crowned. It belongs to one of the employees of the establishment, and its owner conducts me to a comfortable sofa, then trips lightly through a little door opposite to inform Miss Anthony of my presence. I glance about me. . . . Actually a neat carpet on the floor, a substantial round table covered by a pretty cloth, engravings and photographs hung thickly over the clear white walls. Here is Lucretia Mott's saintly face, beautiful with eternal youth; there Mary Wollstonecraft looking into futurity with earnest eyes. In an arched recess are shelves containing books and piles of pamphlets, speeches and essays of Stuart Mill, Wendell Phillips, Higginson, Curtis. Two screens extend across the front of the room, inclosing a little space around the two large windows which give light, air and glimpses of City Hall park. Glancing around the corner we see editor Pillsbury seated at his desk by the further window. Opposite is another desk covered with brown wrappers and mailing books. Close against the screen stands yet another, at which sits the bookkeeper, an energetic young woman who ably manages all the business affairs of The Revolution. There's an atmosphere of womanly purity and delicacy about the place; everything is refreshingly neat and clean, and suggestive of reform.

Ah! here comes Susan--the determined--the invincible, the Susan who is possibly destined to be Vice-President or Secretary of State some of these days! What a delicious thought! I tremble as she steps rapidly toward me and I perceive in her hand a most statesmanlike roll of MSS. The eyes scan me coolly and interrogatively but the pleasant voice gives me a yet pleasanter greeting. There's something very attractive, even fascinating in that voice--a faint echo of the alto vibration--the tone of power. Her smile is very sweet and genial, and lights up the pale, worn face rarely. She talks awhile in her kindly, incisive way. "We're not foolishly or blindly aggressive," says she, tersely; "we don't lead a fight against the true and noble institutions of the world. We only seek to substitute for various barbarian ideas, those of a higher civilization--to develop a race of earnest, thoughtful, conscientious women." And I thought as I remembered various newspaper attacks, that here was not much to object to. The world is the better for thee, Susan.

She rises; "Come, let me introduce you to Mrs. Stanton." And we walk into the

inner sanctum, a tiny bit of a room, nicely carpeted, one-windowed and furnished with two desks, two chairs, a little table--and the senior editor, Mrs. Stanton. The short, substantial figure, with its handsome black dress and silver crown of curls, is sufficiently interesting. The fresh, girlish complexion, the laughing blue eyes and jolly voice are yet more so. Beside her stands her sixteen-year-old daughter, who is as plump, as jolly, as laughing-eyed as her mother. We study Cady Stanton's handsome face as she talks on rapidly and facetiously. Nothing little or mean in that face; no line of distrust or irony; neither are there wrinkles of care--life has been pleasant to this woman.

We hear a bustle in the outer room--rapid voices and laughing questions--then the door is suddenly thrown open and in steps a young Aurora, habited in a fur-trimmed cloak, with a jaunty black velvet cap and snowy feather set upon her dark clustering curls. What sprite is this, whose eyes flash and sparkle with a thousand happy thoughts, whose dimples and rosy lips and white teeth make so charming a picture? "My dear Anna," says Susan, starting up, and there's a

|

| Anna Dickinson |

shower of kisses. Then follows an introduction to Anna Dickinson. As we clasp hands for a moment, I look into the great gray eyes that have flashed with indignation and grown moist with pity before thousands of audiences. They are radiant with mirth now, beaming as a child's, and with graceful abandon she throws herself into a chair and begins a ripple of gay talk. The two pretty assistants come in and look at her with loving eyes; we all cluster around while she wittily recounts her recent lecturing experience.

As the little lady keeps up her merry talk, I think over these three representative women. The white-haired, comely matron sitting there hand-in-hand with her daughter, intellectual, large-hearted, high-souled--a mother of men; the grave, energetic old maid--an executive power; the glorious girl, who, without a thought of self, demands in eloquent tones justice and liberty for all, and prophesies like an oracle of old. May we not hope that America's coming woman will combine these salient qualities, and with all the powers of mind, soul and heart vivified and developed in a liberal atmosphere, prove herself the noblest creature in the world? And so I leave them there--the pleasant group--faithful in their work, happy in their hopes.

Train's financial support ceased by May 1869, and the paper began to operate in debt. Anthony insisted on expensive, high-quality printing equipment, and she paid women workers the high wages she thought they deserved. She banned any advertisements for alcohol- and morphine-laden patent medicines; all such medicines were abhorrent to her. However, revenue from non-patent-medicine advertisements was too low to cover costs.

In the autumn of 1868, Douglass declined an invitation to speak to a women’s suffrage meeting in Washington. He justified his decision in a letter to Josephine Griffing:

The right of woman to vote is as sacred in my judgment as that of man, and I am quite willing at any time to hold up both hands in favor of this right. It does not however follow that I can come to Washington or go elsewhere to deliver lectures upon this special subject. I am now devoting myself to a cause [if] not more sacred, certainly more urgent, because it is one of life and death to the long enslaved people of this country, and this is: negro suffrage. While the negro is mobbed, beaten, shot, stabbed, hanged, burnt and is the target of all that is malignant in the North and all that is murderous in the South, his claims may be preferred by me without exposing in any wise myself to the imputation of narrowness or meanness towards the cause of woman. … She is the victim of abuses, to be sure, but it cannot be pretended I think that her cause is as urgent as … ours. I never suspected you of sympathizing with Miss Anthony and Mrs. Stanton in their course. Their principle is: that no negro shall be enfranchised while woman is not.

Anthony and Stanton also attacked the Republican Party and worked to develop connections with the Democrats. They wrote a letter to the 1868 Democratic National Convention that criticized Republican sponsorship of the Fourteenth Amendment (which granted citizenship to black men but introduced the word "male" into the Constitution), saying,

While the dominant party has with one hand lifted up two million black men and crowned them with the honor and dignity of citizenship, with the other it has dethroned fifteen million white women—their own mothers and sisters, their own wives and daughters—and cast them under the heel of the lowest orders of manhood.

Their attempt to collaborate with Democrats did not go far, however, because their politics were too pro-black for the Democratic Party of that era. Southern Democrats had already begun the process of re-establishing white supremacy there, including violent suppression of the voting rights of blacks.

Several AERA members expressed anger and dismay over the activities of Stanton and Anthony during this period, including their deal with Train that gave him space to express his views in The Revolution. Some, including Lucretia Mott, president of the organization, and African Americans Frederick Douglass and Frances Harper, voiced their disagreements with Stanton and Anthony but continued to maintain working relationships with them. In the case of Lucy Stone, however, the disputes of this period led to a personal rift, one that had important consequences for the women's movement.

L&WofSBA:

Notwithstanding the protests and petitions of the women, the Fourteenth Amendment had been formally declared ratified July 28, 1868, the word "male" being thereby three times branded on the Constitution.

In the resolutions of Senator Pomeroy and Mr. Julian, however, they found new

|

| George Julian |

hope and fresh courage. They had learned that the Federal Constitution could be so amended as to enfranchise a million men who but yesterday were plantation slaves. Here, then, was the power which must be invoked for the enfranchisement of women. From the office of The Revolution went out thousands of petitions to the women of the country to be circulated in the interests of an amendment to regulate the suffrage without making distinctions of sex. It was decided that a convention should be held in Washington in order to meet the legislators on their own ground. A suffrage association had been formed in that city with Josephine S. Griffing, founder of the Freedmen's Bureau, president; Hamilton Willcox, secretary. This was the first ever held in the capital, and it brought many new and valuable workers into the field. Clara

|

| Clara Barton |

Barton here made her first appearance at a woman suffrage meeting, and was a true and consistent advocate of the principle from that day forward. The venerable Lucretia Mott presided, and Senator Pomeroy opened the convention with an eloquent speech, January 19, 1869. A feature of this occasion was the appearance of several young colored orators, speaking in opposition to suffrage for women and denouncing them for jeopardizing the black man's claim to the ballot by insisting upon their own. One of them, George Downing, standing by the side of Lucretia Mott, declared that God intended the male should dominate the female everywhere! Another was a son of Robert Purvis, who was earnestly and publicly rebuked by his father. Edward M. Davis, son-in-law of Lucretia Mott, also condemned the women for their temerity and severely criticised the resolutions, which demanded the same political rights for women as for negro men.

. . . The passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, and the

|

| Samuel Pomeroy |

Fourteenth establishing the citizenship of the negro, did not prove sufficient to protect him in his right of suffrage and, although Sumner and other Republican leaders contended that another amendment was not necessary for this, the majority of the party did not share this opinion and it became evident that one would have to be added. Those proposed by Pomeroy and Julian securing universal suffrage were brushed aside without debate, and the following was submitted by Congress to the State legislatures, February 27, 1869:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States, or by any State, on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude."

In March 1869, Stanton and Anthony came across Douglass by chance “on the way from Galena, Illinois to Toledo, Ohio.” According to Stanton, writing for The Revolution, Douglass was:

dressed in a cap and great circular cape of wolf skins. He really presented a

|

| Frederick Douglass |

most formidable and ferocious aspect … As I had been talking against the pending amendment of ‘manhood suffrage,’ I trembled in my shoes and was almost as paralyzed as Red Riding Hood in a similar encounter. But unlike the little maiden, I had a friend at hand and, as usual, in the hour of danger, I fell back in the shadow of Miss Anthony, who stepped forward bravely and took the wolf by the hand. His hearty words of welcome and gracious smile reassured me … Our joy in shaking hands here and there with Douglass, Tilton, and Anna Dickinson, through the West was like meeting ships at sea; as pleasant and as fleeting. Douglass’s hair is fast becoming as white as snow, which adds greatly to the dignity and purity of his countenance … We had an earnest debate with Douglass as far as we journeyed together, and were glad to find that he was gradually working up to our ideas on the question of Suffrage. … As he will attend the Woman Suffrage Anniversary in New York in May, we shall have an opportunity for a full and free discussion of the whole question.”

At the climactic AERA annual meeting on May 12, 1869, Stephen Symonds Foster objected to the renomination of Stanton and Anthony as officers. He denounced their willingness to associate with George Francis Train despite his disparagement of blacks, and he charged them with advocating "Educated Suffrage", thereby repudiating the AERA's principle of universal suffrage. Henry Blackwell responded, "Miss Anthony and Mrs. Stanton believe in the right of the negro to vote. We are united on that point. There is no question of principle between us." Frederick Douglass objected to Stanton's use of "Sambo" to represent black men in an article she had written for The Revolution.

The majority of the attendees supported the pending Fifteenth Amendment, but debate was contentious. Douglass said, "I do not see how anyone can pretend that there is the same urgency in giving the ballot to woman as to the negro. With us, the matter is a question of life and death, at least in fifteen States of the Union." Anthony replied, "Mr. Douglass talks about the wrongs of the negro; but with all the outrages that he to-day suffers, he would not exchange his sex and take the place of Elizabeth Cady Stanton."

|

| Lucy Stone |