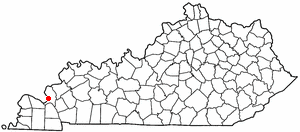

William Martin Dickson was born in Lexington, Indiana. He lost his father, a farmer, at the age of 8.

|

| Lexington, Indiana |

Despite financial hardships, Dickson managed to graduate from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. According to family history, he swept out classrooms to pay tuition.

After graduation, he studied law while supporting himself as a schoolteacher. He was admitted to the Kentucky bar in 1848. Over the next two years, he put himself through Harvard Law School.

|

| Miami University |

He was 33 years old when the Civil War began.

|

| Cincinnati, 1850 |

Returning to the Midwest, he settled in Cincinnati and made a living as a teacher, tutor, and reporter for the Cincinnati Times.

On October 18, 1852, he married Annie Marie Parker of Lexington, Kentucky, a first cousin of Mary Todd Lincoln. They eventually had six children: Parker (1853-1919), William (1856-1915), Mary (born & died in 1860), Annie (1862-1864), Jennie (1865-1894) and Lillie (1870-1873).

In 1853, six months after his marriage, running on the Independent ticket, Dickson won election as prosecuting attorney of the Cincinnati police court.

|

| Alphonso Taft |

He resigned in April, 1854, to form a successful law partnership with Alphonso Taft (father of the future President William Howard Taft) and Thomas Marshall Key.

|

| Abraham Lincoln |

Abraham Lincoln came to stay with the Dicksons in Cincinnati for a week in September 1855 while he worked on a legal case. The McCormick-Manny lawsuit gave Lincoln a chance to earn some substantial fees and gain more recognition as a courtroom lawyer. The two companies in Illinois were making reaping machines for farmers: the Cyrus McCormick Company of Chicago, the oldest and biggest company, and the Manny Company of Rockford, Illinois. McCormick sued Manny for infringement of patent, a charge the company's owner, John H. Manny, denied. The case was to be heard in U.S. District Court in Chicago; and Manny, who had already hired some well-known lawyers who were experts in patent law, decided to hire Lincoln, who knew the courts in Illinois. Lincoln, with a $500 advance from Manny, began studying up on reapers and patent law.

|

| George Harding |

However, he was unable to contact the lead attorney, Peter H. Watson of Washington, D.C. Watson had brought on two other lawyers, George Harding of Cincinnati and Edwin Stanton of Pittsburgh to help try the case.

|

| Edwin Stanton with son |

Watson, Harding and Stanton froze Lincoln out. In August 1855, Lincoln learned by accident that the case had been moved from Chicago to Cincinnati. Watson did not respond to Lincoln's letters, so in mid-September, Lincoln showed up in Cincinnati. The other lawyers were staying at the Burnet House hotel, on the northwest corner of Third and Vine. Lincoln stayed in the home of Dickson and his wife, Annie.

|

| Burnet House Hotel |

When, during the trial, Judge John McLean had lawyers from both sides at his Clifton home for dinner, Lincoln was not invited. Stanton said he would not associate with "such a damned, gawky, long-armed ape as that." Lincoln, he told his fellow lawyers, was a "long, lank creature from Illinois, wearing a dirty linen duster for a coat and the back of which perspiration had splotched with wide stains that resembled a map of the continent." Lincoln was told by the other lawyers that he would not be sitting at the table with the lawyers in the courtroom.

Years later, Dickson wrote:

Mr. Lincoln had prepared himself with the greatest care; his ambition was to speak in the case and measure words with the renowned lawyer from Baltimore. He came with the fond hope for making fame in a forensic contest with Reverdy Johnson. He was pushed aside, humiliated and mortified. . . . He seemed to be greatly depressed; and he gave evidence of that tendency to melancholy which so marked his character.

Manny ended up winning the case; Lincoln left for home having not played a part in it. Later, Watson sent Lincoln a check for $2,000. Lincoln returned it, saying he hadn't done enough to earn it. Watson insisted and sent it back. This time, Lincoln kept it, splitting the money with his Springfield law partner, William Herndon.

He later wrote to Dickson, "You have made my stay here most agreeable; and I am a thousand times obliged to you. . . . But in reply to your request for me to come again I must say to you I never expect to be in Cincinnati again. I have nothing against the city, but things have so happened here as to make it undesirable for me ever to return here."

In 1858, at age 31, Dickson was appointed judge of the Common Pleas Court. Dickson maintained an active role in politics despite never again holding elective office after his stint as public prosecutor. He was an early and prominent founding member of the Republican Party. After serving as an Ohio presidential elector in 1860, he became part of Washington, D.C., political circles, associating with Abraham Lincoln, Edwin Stanton, and Salmon Chase.

|

| Salmon Chase |

In 1861, when the Civil War began, one

of Dickson's law partners, Thomas Marshall Key, became the confidential aide and political advisor to General George McClellan. McClellan offered Dickson a position as assistant judge advocate, but Dickson declined the appointment after learning of McClellan's contemptuous attitude toward President Lincoln.

|

Abraham Lincoln, George McClellan,

and Thomas Marshall Key |

On August 30, 1862, Confederate troops defeated Union forces in Richmond, Kentucky, and appeared to be moving further north toward Ohio. Governor David Tod called upon all loyal Ohioans to help defend their southern borders. Thousands of white men reported for duty, and these minutemen earned the nickname "The Squirrel Hunters."

|

| David Tod |

On September 2, hundreds of black males were violently and brutally taken from their homes, work, and farms by the Cincinnati Police. Cincinnati Mayor George Hatch was rumored to have little opposition to the Confederate Army, and even less respect for colored citizens. The African-American men who were taken by the police were held overnight in a mule-pen with no way of contacting their families.

The next day, September 3, General Lew Wallace appointed Dickson to be Acting Colonel in command of the black workers. Dickson found his troops laboring at Fort Mitchel. They were weary, anxious about their families, and indignant about the treatment they had received the night before. In the evening, Dickson dismissed the men to tend to their families as well as gather personal supplies for the days of work ahead. He promised them that he was forming the brigade for fatigue duty and they "should be kept together as a distinct body. . . that they should receive protection and the same treatment as white men. . . and that their sense of duty and honor would cause them to obey all orders given, and thus prevent the necessity of any compulsion." Dickson sent the 400 men home with orders to report back to him the next day at 5:00 a.m.

|

| Dickson and Wallace on Black Brigade Memorial |

On September 4, approximately 700 black men reported for duty. These men were divided into three small regiments and seventeen companies. They marched under a flag bearing the name "The Black Brigade of Cincinnati." The men of the Black Brigade performed many jobs in defending Cincinnati. The main tasks they were in charge of were making military roads, digging trenches and riffle-pits, felling forests, and building forts and magazines. During their first week of service, they received no compensation for their labor. The second week they were given $1.00 per day, and the third week they received $1.50 per day.

A letter in The Tribune dated September 7, said

While all have done well, the negroes, as a class, must bear away the palm. When martial law was declared, a few prominent colored men tendered their services in any capacity desired. As soon as it became known that they would be accepted, Mayor Hatch's police commenced arresting them everywhere, dragging them away from their houses and places of business without a moment's notice, shutting them up in negro-pens, and subjecting them to the grossest abuse and indignity. Mr. Hatch is charged with secession proclivities. During the recent riots against the negroes, the animus of his police was entirely hostile to them, and many outrages were committed upon that helpless and unoffending class. On this occasion, the same course was pursued. No opportunity was afforded the negro to volunteer; but they were treated as public enemies. They were taken over the river, ostensibly to work upon the fortification; but were scattered, detailed as cooks for white regiments, some of them half-starved, and all so much abused that it finally caused a great outcry. When Gen. Wallace's attention was called to the matter, he requested Judge William M. Dickson, a prominent citizen, who is related by marriage to President Lincoln, to take the whole matter in charge. Judge Dickson undertook the thankless task: organized the negroes into two regiments of three hundred each, made the proper provision for their comfort, and set them at work upon the trenches. They have accomplished more than any other six hundred of the whole eight thousand men upon the fortifications. Their work has been entirely voluntary. Judge Dickson informed them at the outset that all could go home who chose; that it must he entirely a labor of love with them. Only one man of the whole number has availed himself of the privilege; the rest have all worked cheerfully and efficiently. One of the regiments is officered by white captains, the other by negroes. The latter proved so decidedly superior that both regiments will hereafter be commanded by officers of their own race. They are not only working, but drilling; and they already go through some of the simpler military movements very creditably. Wherever they appear, they are cheered by our troops. Last night, one of the colored regiments, coming off duty for twenty-four hours, was halted in front of headquarters, at the Burnet House, front faced, and gave three rousing cheers for Gen. Wallace, and three more for Judge Dickson.

At one point the black workers were only a mile away from the line of battle, unarmed, with only the cavalry between them and the Confederate troops.

|

| Black Brigade Monument in Cincinnati, Ohio |

By September 11, Confederate troops were retreating back into Kentucky. During a speech, General Wallace declared, "When the history of Cincinnati during the past two weeks comes to be written up, it will be said that it was the spades and not the guns that saved the city from attack by the Rebels."

|

| Black Brigade Memorial, Cincinnati, Ohio |

On September 20, 1862, the Black Brigade was dismissed to return to their homes and families. They presented Dickson with a ceremonial sword to thank him for his leadership and kindness.

Marshall P. H. Jones stepped forward and addressed the commander:

Colonel Dickson: The second day of September will ever be memorable in the history of the colored citizens of Cincinnati. Previous to that date the proffered aid of that class of citizens, for war purposes, was coldly, we may add, forcibly rejected. Many calls for aid and assistance to suppress this gigantic rebel lion, as full in their demands as the one on that day, so far as this class of persons is concerned, had been made, yet there was no demand for our services.

Deep in the memory of colored citizens of Cincinnati is written indelibly that eventful day, the second of September, 1862. We were torn from our homes, from the streets, from our shops, and driven to the mule-pen on Plum Street at the point of the bayonet, without any definite knowledge of what we were wanted for. Dismay and tenor spread among the women and children, because of the brutal manner in which arrests were made. The colored people are generally loyal. This undue method of enlisting them into the service of Uncle Sam had the appearance (though false) that the colored people had to be driven, at the point of the bayonet, to protect their homes, their wives, and their children. They went unwillingly, under such circumstances.

Contrast this with the alacrity with which they responded to the gentlemanly request, even before they knew they would be remunerated for their services.

Sir, I have been selected by the members of the Black Brigade to thank you --deeply thank you -- for the very great interest you have taken in our welfare, for your exertions and final success in collecting all of the different working parties into one brigade, for the kindness you have manifested to us in these trying times. We deeply thank you; our mothers thank you; our sweethearts thank you; our children will rise up, thank you, and call you blessed.

. . . Therefore, as a small expression of the high esteem the members of the Black Brigade entertain for you, they all, each and every one, present you this sword, the emblem of protection knowing that, whenever it is drawn, it will be drawn in favor of freedom. And should you be called on, under other circumstances, to demand the services of the Black Brigade, you will find they will rally around your standard in the defense of our country.

Dickson then thanked them:

Soldiers of the Black Brigade! You have finished the work assigned to you upon the fortifications for the defence of the city. You are now to be discharged.

You have labored faithfully; you have made miles of military roads, miles of rifle-pits, felled hundreds of acres of the largest and loftiest forest trees, built magazines and forts. The hills across yonder river will be a perpetual monument of your labors.

You have, in no spirit of bravado, in no defiance of established prejudice, but in submission to it, intimated to me your willingness to defend with your lives the fortifications your hands have built. Organized companies of men of your race have tendered their services to aid in the defence of the city. In obedience to the policy of the Government, the authorities have denied you this privilege.

In the department of labor permitted, you have, however, rendered a willing and cheerful service. Nor has your zeal been dampened by the cruel treatment received. The citizens, of both sexes, have encouraged you with their smiles and words of approbation; the soldiers have welcomed you as co-laborers in the same great cause. But a portion of the police, ruffians in character, early learning that your services were accepted, and seeking to deprive you of the honor of voluntary labor, before opportunity was given you to proceed to the field, rudely seized you in the streets, in your places of business, in your homes, everywhere, hurried you into filthy pens, thence across the river to the fortifications, not permitting you to make any preparation for camp-life. You have borne this with the accustomed patience of your race; and when, under more favorable auspices, you have received only the protection due to a, common humanity, you have labored cheerfully and effectively.

Go to your homes with the consciousness of having performed your duty, -- of deserving, if you do not receive, the protection of the law, and bearing with you the gratitude and respect of all honorable men.

You have learned to suffer and to wait; but, in your hours of adversity, remember that the same God who has numbered the hairs of our heads, who watches over even the fate of a sparrow, is the God of your race as well as mine. The sweat-blood which the nation is now shedding at every pore is an awful warning of how fearful a thing it is to oppress the humblest being.

|

Statue of William Dickson

receiving Black Brigade sword from Marshall P. H. Jones |

Dickson accepted the gift and led his troops through the streets with music playing and banners flying.

When the Civil War officially ended in April, 1865, the nation’s attention turned toward the questions of how to reunify the nation and “reconstruct” the states of the former Confederacy. In December 1865, at Oberlin College, Dickson delivered an address titled The Absolute Equality of all before the law, the only true basis of Reconstruction:

The long war with its destruction of precious life, its fearful waste, its harrowing anxieties, is now happily over. It has not been a failure. The object for which it was waged, has been completely attained. The rebellion is suppressed, and the territorial integrity of the Union is secure.

. . . The rebellion has gained nothing by its violation of law, nothing by its appeal from the decision of the ballot-box to the trial by battle. . . .

But, my friends, our work is only half done; reconstruction remains.

Force produces physical unity; this is not the basis of our institutions. We may not, with safety to ourselves, maintain permanently military control of rebel States. . . . Yet the rebels have invoked the war power; it is not for them to say when or how we shall lay it aside. We may not do this until the public safety permits. . . .

The fact is, and we might as well look it squarely in the face, with a few unimportant exceptions, the Southern whites yield sullenly and reluctantly to the decision of the sword. They are conquered, not converted.

Do not mistake me; I ask them of no unmanly self-abasement. I would not have them otherwise than proud of the prowess they have exhibited in the contest. But before I would give them a voice in the affairs of the nation, a vote to control your and my concerns, I would have a guaranty that this voice and this vote would be directed to the common good, that these would not be merely new and more dangerous weapons in their hands, to carry on the war against the Union.

. . . For example, many of these men are largely interested in the rebel debt. Can it be expected that they will vote for the repudiation of this debt and the payment of the National debt, incurred in their coercion? . . .

These rebel men have been accustomed all the days of their lives to eat their bread by the sweat of another's face; to make this condition of things perpetual, they have imbrued their hands in a brother's blood.

They have failed; henceforth they must share the common doom of the sons of Adam. They must work. The slave is free; and the immortal proclamation pledges the public faith, by the most sacred of obligations, to the maintenance of his freedom.

. . . At the commencement of this war, it was a common declaration of those who were in sympathy with the rebels, that the rebellion could not be put down; that history did not furnish an example of eight or ten millions of people determined on independence being conquered. These opinions were generally held by the rulers of Europe. But there was one important element left out of the calculation, namely, nearly one half of the population of the rebel States, were the determined enemies of the rebellion, and this half constituted the laboring class . This half neutralized, in the long run, the other half.

While I am not one of those who place the bravery of the negro soldiers above that of the white, it is a fact which will hardly denied, that but for the opposition of the entire negro population to the rebel cause, we could scarcely have succeeded; surely, had this force been added to the rebel side, we could not.

. . . I would so reconstruct the Southern States, that while I gave to the disloyal half their full equality before the law, I would paralyze their disloyal purposes by giving a like equality to the loyal half. What wrong is there is this? I give to the men who, for four years have been to destroy the nation full rights--the same which you and I have. The only condition imposed, is, that their loyal follow citizens shall have the problem of reconstructions is full harmony with the representative principle and all our institutions. It will in a brief time remove pro-consular governments, and restore the normal condition of all the States. The country can then rest satisfied that a full guaranty against any efforts of the rebels to do injury, under a restored government. This solution introduces no new element, no new principle into our government. It is but the complete application of the principles of our fathers, set forth in the declaration of independence.

. . . The rebels well knew, when they appealed to the tribunal of the sword, what the judgment must be, if the decision should be adverse to them. By the universal laws of war, the conquering power may impose such conditions of settlement, looking to its own safety and welfare, as it pleases; only these must not be in violation of the laws of humanity. This principle clearly gives the Government power to adopt the plan of reconstruction proposed. Surely it is not variance with the laws of humanity. This power also, maybe deprived from the present condition of the rebel States, and the peculiar structure of our Government. . . .

It is said there is a deeply rooted antagonism between the black and white races, forbidding their remaining together in the same country. If this is a fact, it is a very sad one; but it would not furnish an objection, specially against the plan of reconstruction under consideration. It would seem to apply equally to all plans. It is rather the statement of an insurmountable difficulty, than the solution of one. It is as if one were to complain of the light of the sun, or of the alternation of the seasons. For this is not a question of introducing four millions of negroes here; they are here now, and all plans that have ever been suggested for effecting their separation are purely chimerical. They cannot be separated, and yet, the declaration is, they cannot remain together. The ease would seem to be hopeless.

But happily this declaration is not true. The prejudices between these races are not different in character from other prejudices. There are prejudices between Irishmen and Englishmen; between Catholics and Protestants: between Christians and Jews. These have often been very violent and wars have grown out of them. Not, however, because of their differences but because one race sought to subordinate to itself another, or one sect sought to impose its tenets upon another. Peace prevailed when each race and each sect attended to its own business. When our fathers framed our Constitution, they understood these principles and applied them. They the different races and sects, by securing to each absolute equality before the law.

. . . Now we have the opportunity of applying these principles to this race and of thus removing the last exception. I would make the application. Prejudice yields to power and interest. . .

Again, it is objected, that the Southern negro is ignorant and unfit to vote. He seems to have been intelligent enough to be loyal, which was more than his master was. But I do not deny the ignorance; their condition of slavery forbids that it could be otherwise. Yet they share this ignorance in common with the poor whites; and I would be willing to apply to both these classes an educational test. Still I would not recommend this. Freedom is the school in which freemen are to be taught, and the ballot-box is a wonderful educator.

. . . As the force of the negro must enter into the formation of our civilization, it is to the interest of the white man not less than of the black man, that this force should be for good. It cannot be, however, unless the negro is moral, intelligent and industrious. How can we give him these desirable characteristics? We have only to consider the conditions under which white men have become moral, intelligent, and industrious, and apply these to the black man.

Our proposition thus becomes very simple; we must educate him and place before him the rewards of good conduct and the penalties of bad conduct.

We must give him entire equality before the law and all these things will follow. . . . We must educate him, and give him the condition of self-respect, if we would have his influence for good upon our civilization. . . And further, if we educate him and place him in a position in which he will respect himself, we may expect the most gratifying results to the common good. In an economic view this is a matter of the greatest moment. The increased production of an intelligent, self-respecting and industrious population can hardly be estimated. In the South thrift will take the place of waste; voluntary labor directed by an enlightened self-interest will take the place of compulsory labor directed by the lash; provident abstinence will save for a reserved fund, that which has heretofore been lost in careless expenditure. Fixed capital will thus arise; towns will spring up; the industrial arts will be cultivated; and prosperity and wealth will abound where want and poverty have prevailed. That rich southern soil with its generous climate, is a mine of untold wealth. It needs but the hand of free industry to bring it forth. All this would greatly contribute to lightening the load of our debt. These grateful people would gladly aid in the payment of the ransom for their redemption.

. . . The Golden Rule of our most holy religion commanding us to do unto others as we would that they should do unto us, requires it.

My friends, when I leave here should you think of what I have said, remember that I have not proposed to take anything from any man,--no, not even from the rebels. I indeed propose to them, their full restoration to all the rights of citizenship, as fully as we possess them our selves. I seek nothing which need be offensive to them; nothing which is unknown to their own history. In their better days, before slavery became their absorbing thought, free black men voted in many if not all the Southern States. While we are in the way of restoring the forfeited rights of the rebels, let us give to the loyal black man, now free, his ancient right to vote--a gift that costs no one anything, but the withholding of which from him makes him poor indeed. Nay, it is for the interest of the South far more than of the North that this should be done.

. . . If this plan of reconstruction is adopted a great and happy and prosperous future is open to the South.

But if the contrary course is taken; if the negro is to continue a poor and despised being, with no rights which a white man is bound to respect; if he is to be the subject of insult and outrage, with no other protection than the strength of his arm,--then indeed the future of the South is very dark. . .

Our fathers, yielding to the embarrassments of the day permitted negro slavery to remain, with the expectation, it is true, that it would soon pass away. Alas, what a fearful mistake! This action has been the cause of all our woe. Shall we repeat this mistake? Shall we learn no lesson from this sad experience? God grant that it may be otherwise. Let us catch the inspiration of our Martyr President at the field of Gettysburg; let us join in his prayer "That this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that Government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

Within a year of the war's end, Dickson, only thirty-nine, became ill from "nervous prostration." For the rest of his life he lived as a semi-invalid, and removed himself from the legal and political scene. However, he maintained a keen interest which he expressed in his private correspondence and in essays and letters written for publication, on such topics as reconstruction, black suffrage, and civil service reform. He had many correspondents and personal associations, and included some of the leading figures of the era.

Dickson wrote of Lincoln with respect, affection and honesty: he analyzed Lincoln's character and political talents, noting both strengths and weaknesses. An essay, "Abraham Lincoln at Cincinnati," written for Harper's Magazine in 1884, described Lincoln's visits to the city during the course of his career. It discussed his long relationship with Stephen A. Douglas, and described his legal and political acumen and the force of his personality.

|

| George McClellan |

A memoir written later in Dickson's life features colorful characterizations of McClellan, Lincoln, and the Washington scene early in the war. He wrote an essay, "A Leaf from the Unwritten History of the Rebellion," in response to the publication of George McClellan's autobiography, which was published in 1887. Dickson's essay damned McClellan as a weak and cautious leader who "organized the army not for victory, but for defeat," and whose influence remained long after he himself departed: "His impress remained almost to the end. His army could stand up and be killed; but it never had the confidence that leads to victory." He characterized McClellan's headquarters as a den of intrigue and plotting, with one element so loyal to McClellan that they would have overthrown the government for him. McClellan himself, Dickson believed, despised Lincoln both "as the representative of the abolition sentiment" and for his "ungainly gait and low birth." He permitted his staff to make the president " a subject for ridicule and merriment." One of his aides referred to Lincoln as "the d-----d old Gorilla."

Dickson also wrote, in an unpublished draft, in defense of his former partner Thomas Marshall Key. Stanton's friend, Don Piatt, wrote in his book, Memories of the Men Who Saved the Union, that Key was the "evil genius" behind McClellan. Dickson acknowledged Key's influence but laid the credit for McClellan's failure at McClellan's own feet.

|

| Don Piatt |

Dickson considered himself a Republican, one of the founders of the party, and despaired at the corruption and machine politics which increasingly characterized his party during the Gilded Age of late nineteenth century America. Dickson watched and wrote with distaste as his party betrayed, in his eyes, the ideals of its originators, to become the voice of corporate power and government by class division.

|

| George William Curtis |

During a correspondence of over 20 years with his longtime friend George William Curtis, social reformer and editor of Harper's Weekly, Dickson commiserated and argued over the fortunes and philosophy of the Republican party and its leading lights. Topics of discussion include the Grant administration, the Hayes presidency, Roscoe Conkling, Grover Cleveland and civil service reform, tariff issues, the character and career of James Blaine, the Harrison administration, various Republican office-holders, and their shared view of the decline of their beloved party.

Near the end of his life Dickson resigned his membership in the Lincoln Club and supported the Democrats in their tariff reform efforts, joining with his friend Curtis in condemning the Republican party as "a boodle party" which has lost its "moral enthusiasm."

Dickson's wife, Annie, died in 1885 after more than 30 years of marriage.

Dickson died on October 15, 1889, in a noontime accident on the Mount Auburn incline railway in Cincinnati. Nine passengers had entered the car at the foot of the incline. A cable broke just as the car reached the top, and it went crashing down into the passenger station below. The iron gate that formed the lower end of the track was thrown sixty feet down the street. Dickson, who was 62 years old, was one of the first of the wounded to die.

|

| Mount Auburn Incline |

From The Cincinnati Lancet-Clinic, October 19, 1889:

Last Tuesday the people of this city were horrified with the news of the giving way of the cable and car connection on this inclined plane, by which five persons were instantly killed and as many more mortally or dangerously injured.

|

| Mount Auburn Incline |

He was buried in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati.

|

| Dickson Grave in Spring Grove Cemetery |

His friend George Curtis eulogized Dickson in Harper's Weekly as "one of that most valuable class of citizens who take the most active and intelligent interest in the observation of public affairs, which they seek to influence by the pen."