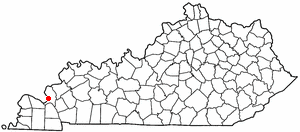

Andrew Jackson Smith was born into slavery in Lyon County, Kentucky, the son of Susan, a slave, and Elijah Smith, who owned her. As a boy, he was called "Andy."

|

| Cumberland River |

He was 18 years old when the Civil War began.

|

| Lyon County, Kentucky |

|

| Location of Smithland, Kentucky |

|

| John Warner |

During the fighting near the Peach Orchard, Smith supplied Warner with horses after the officer had two mounts shot out from under him. Smith was then struck by a "spent minie ball that entered his left temple, rolled just under the skin, and stopped in the middle of his forehead." The bullet was removed by the regimental surgeon. Smith had the scar for the rest of his life.

|

| Alfred Hartwell |

On November 30, 1864, both the 55th and its sister regiment, the 54th Massachusetts, participated in the Battle of Honey Hill in South Carolina. The two units came under heavy fire while crossing a swamp in front of an elevated Confederate position. Confederate fire killed and wounded half of the officers and a third of the enlisted men in Smith's thousand-man regiment. When the 55th's color bearer was killed, Smith took up the battle flags and carried them through the remainder of the fight. It was for this action that Smith was later awarded the Medal of Honor.

Had his actions on that day been properly recorded, he would have been rewarded with the Medal of Honor during his lifetime. The regimental commander, Colonel Hartwell, was severely wounded and carried from the battle early in the fighting. Hartwell completed his battle report at his home while recuperating from his wounds.

Smith was promoted to color sergeant soon after the battle. After the fall of Charleston, Hartwell marched his forces through the city, with the African-American troops at the head of his brigade. They occupied the city and dealt with the large number of refugees. The 55th Massachusetts Colored remained in the area and was later detailed as provost guard at Orangeburg, South Carolina.

Smith received his final discharge at Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina on August 29, 1865. He then went to Clinton, Illinois for a short time. He later moved to Eddyville, Kentucky where he used his mustering out pay to buy land. He eventually owned about a thousand acres.

The 1870 census listed Andrew Jackson Smith at age 26 in Lyon, Kentucky, with his wife, Mandy Smith 27. The 1910 census listed Andrew Jackson Smith at age 67, widowed.

|

| Published diary of Burt G. Wilder |

Among the letters written to support Smith’s application was one written by John Warner’s son, Vespasian, to Dr. Wilder on March 10, 1917:

Dear Sir:

Mr. Andy Smith of Grand River, Ky., having asked me to write you what I remember in relation to a wound he received at the battle of Shiloh, I will state that for some time before that battle he had been a servant of my father, who was the Major and afterwards Lieutenant Colonel in command of the 41st Illinois Volunteer Infantry, and when the battle opened, my father told Andy to keep him in sight with a canteen of water, and if he, my father, should fall, to come to him with the water.

That sometime after my father’s regiment became engaged the horse on which he was mounted was wounded and my father was dismounted and turning found Andy standing close to him and giving the wounded horse to Andy, told him to take it to the rear and stay there.

A short time afterwards a horse from which some Confederate had been shot, galloped out between the lines and my father rushed out, caught and mounted him.

Soon afterward this second horse was wounded and my father again dismounted and turning, found Andy standing close to him again and handing the second horse to Andy, told him to take it back and keep out of danger, and just then Andy received a gun shot wound in the head from the enemy. The above is all I remember of the matter.

Andy was certainly a brave and loyal boy.

Yours truly,

Vespasian Warner

|

| Andrew Jackson Smith, later in his life |

Andrew Jackson Smith died on March 4, 1932 at age 88.

|

| Grave of Andrew Jackson Smith |

|

Catherine Bowman and Andrew Smith Bowman at the unveiling of the commemorative Historic Marker placed approximately 3 miles south of Grand Rivers in Lyon County

Andrew Bowman of Indianapolis, Indiana, Smith’s grandson, was determined that his grandfather would receive the Medal of Honor. He spent several years collecting records, conducting research and working with government officials and a history professor at Illinois State University. Smith's records were found in the National Archives, where they had been since the end of the Civil War.

On January 16, 2001, 137 years after the Battle of Honey Hill, Smith was recognized for his actions. President Bill Clinton presented the Medal of Honor to his 93-year-old daughter, Caruth Smith Washington, along with several other of Smith's descendants during a ceremony at the White House.

|

| Caruth Smith Washington at the Medal of Honor Ceremony for her father, Andrew Jackson Smith |

The award culminated efforts by Washington and her late sister, Susan Shelton, who kept the record of Smith's Civil War service in a meticulous family history. "My mother told me all about Sgt. Smith when I just a baby," said Smith's grandson, Walter Shelton, of Richton Park, Illinois, one of eight family members present at the ceremony.

The family also credited the efforts of Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and former Representative Thomas Ewing (R-Ill.), who pushed legislation through Congress that secured the medal for Smith, as well as Sharon MacDonald, an Illinois State University professor, and Robert Beckman, a Dunlap, Illinois high school history teacher, who found Smith's service records in the National Archives and pursued the case with Durbin and Ewing.

"A wrong righted 84 years too late is a wrong righted nonetheless," Durbin said. "This day has been a long time coming. But, with the dedication of his family and the Illinois State University History Department, Sgt. Andrew Jackson Smith's contribution has finally taken its rightful place in history."

Smith's official Medal of Honor citation reads:

Over 23,000 African Americans in Kentucky enlisted in the Union Army. Only Louisiana provided a larger number.

Caruth Smith Washington died at the age of 104 on November 2012. She was believed to be the last direct descendant of a slave in America, born to Gertrude Catlett Smith and Andrew Jackson Smith. Caruth had been an educator and community activist in California and New York.

Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith, of Clinton, Illinois, a member of the 55th Massachusetts Voluntary Infantry, distinguished himself on 30 November 1864 by saving his regimental colors, after the color bearer was killed during a bloody charge called the Battle of Honey Hill, South Carolina. In the late afternoon, as the 55th Regiment pursued enemy skirmishers and conducted a running fight, they ran into a swampy area backed by a rise where the Confederate Army awaited. The surrounding woods and thick underbrush impeded infantry movement and artillery support. The 55th and 54th regiments formed columns to advance on the enemy position in a flanking movement. As the Confederates repelled other units, the 55th and 54th regiments continued to move into flanking positions. Forced into a narrow gorge crossing a swamp in the face of the enemy position, the 55th's Color-Sergeant was killed by an exploding shell, and Corporal Smith took the Regimental Colors from his hand and carried them through heavy grape and canister fire. Although half of the officers and a third of the enlisted men engaged in the fight were killed or wounded, Corporal Smith continued to expose himself to enemy fire by carrying the colors throughout the battle. Through his actions, the Regimental Colors of the 55th Infantry Regiment were not lost to the enemy. Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith's extraordinary valor in the face of deadly enemy fire is in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon him, the 55th Regiment, and the United States Army.

Over 23,000 African Americans in Kentucky enlisted in the Union Army. Only Louisiana provided a larger number.

Caruth Smith Washington died at the age of 104 on November 2012. She was believed to be the last direct descendant of a slave in America, born to Gertrude Catlett Smith and Andrew Jackson Smith. Caruth had been an educator and community activist in California and New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment