John Woolman was the fourth child and eldest son in a family of thirteen children born to Samuel and Elizabeth Burr Woolman, who belonged to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). Samuel Woolman was a farmer who had inherited his house and farm in Burlington County of the New Jersey colony. John was named after Samuel's father, an early Quaker settler who had arrived in New Jersey in 1678.

Mount Holly, four miles away from the Woolman farm, was a village on Rancocas Creek, a tributary of the Delaware River. In John Woolman's day it was almost entirely a settlement of Friends.

Although the large family spent most of their time on the rural farm, they were educated not only in religion, but also in business, medicine and responsible citizenship.

Although the large family spent most of their time on the rural farm, they were educated not only in religion, but also in business, medicine and responsible citizenship.

As a child, John saw a robin's nest that held hatchlings. John began throwing rocks at the mother robin to see if he could hit her. After killing the mother bird, he was filled with remorse, thinking of the baby birds who had no chance of survival without her. He got the nest down from the tree and quickly killed the hatchlings, believing it to be the most merciful thing to do. This experience weighed on his heart. He was inspired to love and protect all living things from then on.

On going to a neighbour's house, I saw on the way a robin sitting on her nest, and as I came near she went off; but having young ones, she flew about, and with many cries expressed her concern for them. I stood and threw stones at her, and one striking her, she fell down dead. At first I was pleased with the exploit, but after a few minutes was seized with horror, at having, in a sportive way, killed an innocent creature while she was careful for her young. I beheld her lying dead, and thought those young ones, for which she was so careful, must now perish for want of their dam to nourish them. After some painful considerations on the subject, I climbed up the tree, took all the young birds, and killed them, supposing that better than to leave them to pine away and die miserably. . . . I then went on my errand, and for some hours could think of little else but the cruelties I had committed, and was much troubled.New Jersey's slave population grew from 2,581 in 1726 to nearly 4,000 in 1738. Slaves accounted for about 12 percent of the colony's population up to the Revolution.

In 1735,when John was 15 years old, a slave in Bergen County who attempted to set fire to a house was burned at the stake in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Slaves from all the neighboring townships, were compelled to be witnesses. Six years later, authorities in Hackensack burned at the stake two slaves who had been setting fire to barns.

In 1741, a series of suspicious fires and reports of slave conspiracy led to general hysteria in New York City. Thirty-one slaves and five whites were executed. New Yorkers claim that Roman Catholic priests are inciting slaves to burn the town on orders from Spain; four whites and 18 blacks are hanged in December, and 13 blacks are burned at the stake.

The west bank of the Hudson River was, like New York and Pennsylvania, originally part of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, and it faced the same chronic shortage of free labor as the rest of the region. The English proprietors who established New Jersey colony after the British take-over in 1664 were even more aggressive than the neighbor states in encouraging African slavery as a means to open up the land for agriculture and commerce. They offered 60 acres of land, per slave, to any man who imported slaves in 1664. In 1702, when New Jersey became a crown colony, Governor Edward Cornbury was dispatched from London with instructions to keep the settlers provided with "a constant and sufficient supply of merchantable Negroes at moderate prices." He likewise was ordered to assist slave traders and "to take especial care that payment be duly made."

But while slaves were encouraged, free blacks were not. Free blacks were barred by law from owning land in colonial New Jersey.

Slaves were especially numerous around Perth Amboy, which was the colony's main port of entry. By 1690, most of the inhabitants of the region owned one or more slaves. From 1713, after a violent slave uprising in New York, to 1768, the colony operated a separate court system to deal with slave crimes. Special punishments for slaves remained on the books until 1788. The colony also had laws meant to discourage slave revolts. Slaves were forbidden to carry firearms when not in the company of their masters, and anyone who gave or lent a gun to a slave faced a fine of 20 shillings. Slaves could not assemble on their own or be in the streets at night.

Slaves were especially numerous around Perth Amboy, which was the colony's main port of entry. By 1690, most of the inhabitants of the region owned one or more slaves. From 1713, after a violent slave uprising in New York, to 1768, the colony operated a separate court system to deal with slave crimes. Special punishments for slaves remained on the books until 1788. The colony also had laws meant to discourage slave revolts. Slaves were forbidden to carry firearms when not in the company of their masters, and anyone who gave or lent a gun to a slave faced a fine of 20 shillings. Slaves could not assemble on their own or be in the streets at night.

John Woolman died 87 years before the Civil War began.

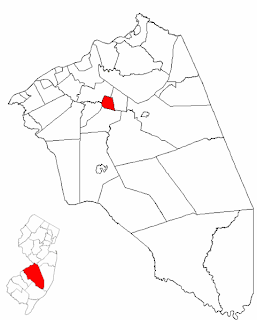

|

| Mount Holly |

As a Friends minister, he began traveling to other meetings and communities in his early twenties:

My esteemed friend Abraham Farrington being about to make a visit to Friends on the eastern side of this province, and having no companion, he proposed to me to go with him; and after a conference with some elderly Friends I agreed to go. We set out on the 5th of Ninth Month, 1743; had an evening meeting at a tavern in Brunswick, a town in which none of our Society dwelt; the room was full and the people quiet. Thence to Amboy, and had an evening meeting in the court-house, to which came many people, amongst whom were several members of Assembly, they being in town on the public affairs of the province. In both these meetings my ancient companion was engaged to preach largely in the love of the gospel. Thence we went to Woodbridge, Rahway, and Plainfield, and had six or seven meetings in places where Friends' meetings are not usually held, chiefly attended by Presbyterians, and my beloved companion was frequently strengthened to publish the word of life amongst them. As for me, I was often silent through the meetings, and when I spake it was with much care, that I might speak only what truth opened. My mind was often tender, and I learned some profitable lessons. We were out about two weeks.

New Jersey narrowly escaped a violent slave uprising in 1743. Somehow word had spread among slaves in Burlington County that Great Britain had outlawed slavery and they were being held in bondage illegally. At midnight on a certain date the slaves agreed to rise up, slit the throats of their masters and the masters' sons, capture the women, plunder the farms, and escape to the French and Indians. A slave let word of the plot slip during an argument with a white man, the authorities were alerted, and after an investigation 30 ringleaders were arrested. Because the plot had not actually gone into effect, only one man was hanged; the rest were sentenced to be flogged or had their ears cut off.

By the age of 26, Woolman had become an independent and successful tradesman. Eventually, he decided that the retail trade demanded too much of his time. He believed he had a calling to preach "truth and light" among Friends and others. In his Journal, he said that:

By the age of 26, Woolman had become an independent and successful tradesman. Eventually, he decided that the retail trade demanded too much of his time. He believed he had a calling to preach "truth and light" among Friends and others. In his Journal, he said that:

My mind, through the power of truth, was in a good degree weaned from the desire of outward greatness, and I was learning to be content with real conveniences, that were not costly, so that a way of life free from much entanglement appeared best for me, though the income might be small. I had several offers of business that appeared profitable, but I did not see my way clear to accept of them, believing they would be attended with more outward care and cumber than was required of me to engage in. I saw that an humble man, with the blessing of the Lord, might live on a little, and that, where the heart was set on greatness, success in business did not satisfy the craving; but that commonly, with an increase of wealth, the desire of wealth increased.

When I ate, drank, and lodged free-cost with people who lived in ease on the hard labor of their slaves I felt uneasy; and as my mind was inward to the Lord, I found this uneasiness return upon me, at times, through the whole visit. Where the masters bore a good share of the burden, and lived frugally, so that their servants were well provided for, and their labor moderate, I felt more easy; but where they lived in a costly way, and laid heavy burdens on their slaves, my exercise was often great, and I frequently had conversation with them in private concerning it.

. . . This trade of importing slaves from their native country being much encouraged amongst them, and the white people and their children so generally living without much labor, was frequently the subject of my serious thoughts. I saw in these southern provinces so many vices and corruptions, increased by this trade and this way of life, that it appeared to me as a dark gloominess hanging over the land; and though now many willingly run into it, yet in future the consequence will be grievous to posterity. I express it as it hath appeared to me, not once, nor twice, but as a matter fixed on my mind.

They traveled about 1,500 miles round-trip in three months. He preached on many topics, including slavery, during this and other trips.

A person at some distance lying sick, his brother came to me to write his will. I knew he had slaves, and, asking his brother, was told he intended to leave them as slaves to his children. As writing is a profitable employ, and as offending sober people was disagreeable to my inclination, I was straitened in my mind; but as I looked to the Lord, he inclined my heart to His testimony. I told the man that I believed the practice of continuing slavery to this people was not right, and that I had a scruple in my mind against doing writings of that kind; that though many in our Society kept them as slaves, still I was not easy to be concerned in it, and desired to be excused from going to write the will. I spake to him in the fear of the Lord, and he made no reply to what I said, but went away; he also had some concerns in the practice, and I thought he was displeased with me. In this case I had fresh confirmation that acting contrary to present outward interest, from a motive of divine love and in regard to truth and righteousness, and thereby incurring the resentments of people, opens the way to a treasure better than silver, and to a friendship exceeding the friendship of men.

. . . Scrupling to do writings relative to keeping slaves has been a means of sundry small trials to me, in which I have so evidently felt my own will set aside, that I think it good to mention a few of them.

Tradesmen and retailers of goods, who depend on their business for a living, are naturally inclined to keep the good-will of their customers; nor is it a pleasant thing for young men to be under any necessity to question the judgment or honesty of elderly men, and more especially of such as have a fair reputation. Deep-rooted customs, though wrong, are not easily altered; but it is the duty of all to be firm in that which they certainly know is right for them.

A charitable, benevolent man, well acquainted with a negro, may, I believe, under some circumstances, keep him in his family as a servant, on no other motives than the negro's good; but man, as man, knows not what shall be after him, nor hath he any assurance that his children will attain to that perfection in wisdom and goodness necessary rightly to exercise such power; hence it is clear to me, that I ought not to be the scribe where wills are drawn in which some children are made sale-masters over others during life.

About this time an ancient man of good esteem in the neighbourhood came to my house to get his will written. He had young negroes, and I asked him privately how he purposed to dispose of them. He told me. I then said, "I cannot write thy will without breaking my own peace," and respectfully gave him my reasons for it. He signified that he had a choice that I should have written it, but as I could not, consistently with my conscience, he did not desire it, and so he got it written by some other person.

A few years after, there being great alterations in his family, he came again to get me to write his will. His negroes were yet young, and his son, to whom he intended to give them, was, since he first spoke to me, from a libertine become a sober young man, and he supposed that I would have been free on that account to write it. We had much friendly talk on the subject, and then deferred it. A few days after he came again and directed their freedom, and I then wrote his will.

Near the time that the last-mentioned Friend first spoke to me, a neighbour received a bad bruise in his body and sent for me to bleed him, which having done, he desired me to write his will. I took notes, and amongst other things he told me to which of his children he gave his young negro. I considered the pain and distress he was in, and knew not how it would end, so I wrote his will, save only that part concerning his slave, and carrying it to his bedside, read it to him. I then told him in a friendly way that I could not write any instruments by which my fellow-creatures were made slaves, without bringing trouble on my own mind. I let him know that I charged nothing for what I had done, and desired to be excused from doing the other part in the way he proposed. We then had a serious conference on the subject; at length, he agreeing to set her free, I finished his will.

Woolman gave up his career as a tradesman and supported himself as a tailor; he also maintained a productive orchard. Geoffrey Plank, author of John Woolman's Path to the Peaceable Kingdom, wrote:

"I think I was most surprised by Woolman’s relative wealth and his commercial dealings. Woolman mentions in his journal that he was a successful draftsman and shopkeeper, but the implications of his financial success did not become clear until I examined his ledger books and worked out some of the details. In the mid- to late 1750s, at exactly the same time that Woolman was beginning to dramatize his opposition to slavery, he invested in hog production. He almost certainly sent pork to sugar-producing plantations in the Caribbean."

Many Friends believed that slavery was bad — even a sin — but they did not universally condemn slaveholding. The wealthiest members held slaves as domestic servants and for other work. Some Friends bought slaves from in order to treat them humanely and educate them. Other Friends seemed to have no opinion against slavery.

Throughout most of the colonial period, opposition to slavery among white Americans was virtually nonexistent. Settlers in the 17th and early 18th centuries came from sharply stratified societies in which the wealthy savagely exploited members of the lower classes. Lacking a later generation’s belief in natural human equality, they saw little reason to question the enslavement of Africans.

The first recorded formal protest against slavery, the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery was signed by German members of a Quaker congregation.

Throughout most of the colonial period, opposition to slavery among white Americans was virtually nonexistent. Settlers in the 17th and early 18th centuries came from sharply stratified societies in which the wealthy savagely exploited members of the lower classes. Lacking a later generation’s belief in natural human equality, they saw little reason to question the enslavement of Africans.

The first recorded formal protest against slavery, the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery was signed by German members of a Quaker congregation.

Woolman married Sarah Ellis, a fellow Quaker, in a ceremony at the Chesterfield Friends Meeting on August 18, 1749.

About this time, believing it good for me to settle, and thinking seriously about a companion, my heart was turned to the Lord with desires that He would give me wisdom to proceed therein agreeably to His will, and He was pleased to give me a well-inclined damsel, Sarah Ellis, to whom I was married the 18th of Eighth Month, 1749.Not much is known about the Woolman's marriage and family life. A daughter, Mary, was born on December 18, 1750, and was the only child to survive to adulthood. A son, William, was born in 1754 and lived only two months.

In 1752 Woolman became clerk of the Burlington Quarterly Meeting.

Woolman and Philadelphia Quaker Anthony Benezet were 'intimate friends,' according to George S. Brookes. Benezet quoted from Woolman, and Woolman borrowed writing strategies from Benezet. It is likely that the two of them worked together on the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Epistle of 1754.

In 1754, Woolman published Some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes:

Let us calmly consider their circumstance: and the better to do it, make their case ours.

Suppose then that our ancestors and we had been exposed to constant servitude, in the more servile and inferior employments of life; that we had been destitute of the help of reading and good company; that amongst ourselves we had had but few wise and pious instructors ; that the religious amongst our superiors seldom took notice of us; that while others in ease had plentifully heaped up the fruit of our labour, we had received barely enough to relieve nature; and being wholly at the command of others, had generally been treated as a contemptible, ignorant part of mankind; should we, in that case, be less abject than they now are?

Again, if oppression be so hard to bear, that a wise man is made mad by it, then a series of oppressions, altering the behaviour and manners of a people, is what may reasonably be expected.

. . . To apply humbly to God for wisdom, that we may thereby be enabled to see things as they are, and as they ought to be, is very needful. Hereby the hidden things of darkness may be brought to light, and the judgment made clear: we shall then consider mankind as brethren.

|

| Considerations on Keeping Negroes Part Second Printed by Benjamin Franklin, 1762 |

Until this year, 1756, I continued to retail goods, besides following my trade as a tailor; about which time I grew uneasy on account of my business growing too cumbersome. I had begun with selling trimmings for garments, and from thence proceeded to sell cloths and linens; and at length, having got a considerable shop of goods, my trade increased every year, and the way to large business appeared open, but I felt a stop in my mind.

Through the mercies of the Almighty, I had, in a good degree, learned to be content with a plain way of living. I had but a small family; and, on serious consideration, believed truth did not require me to engage much in cumbering affairs. It had been my general practice to buy and sell things really useful. Things that served chiefly to please the vain mind in people, I was not easy to trade in; seldom did it; and whenever I did I found it weaken me as a Christian.

The increase of business became my burden; for though my natural inclination was toward merchandise, yet I believed truth required me to live more free from outward cumbers; and there was now a strife in my mind between the two. In this exercise my prayers were put up to the Lord, who graciously heard me, and gave me a heart resigned to His holy will. Then I lessened my outward business, and, as I had opportunity, told my customers of my intentions, that they might consider what shop to turn to; and in a while I wholly laid down merchandise, and followed my trade as a tailor by myself, having no apprentice.

I also had a nursery of apple trees, in which I employed some of my time in hoeing, grafting, trimming, and inoculating.

He was concerned about treatment of animals. In later life, he avoided riding in stagecoaches, as he felt their operation was too often cruel and injurious to the teams of horses. In the season of harvest, when it was customary among farmers to kill a calf or sheep for the laborers, Woolman was unwilling that the animal should be slowly bled to death, as the custom was. To to spare it unnecessary suffering, he had a smooth block of wood prepared for the neck of the creature, and a single blow killed it.

Woolman worked within the Friends' tradition of seeking the guidance of the Spirit of Christ and patiently waiting to achieve unity in the Spirit. As he went from one Friends' meeting to another, he expressed his concern about slaveholding. Gradually various Quaker Meetings began to see the evils of slavery; their minutes reflected their condemnation of the practice.

We set off in the Fifth Month, 1757. . . . We crossed the river Susquehanna, and lodged at William Cox's in Maryland. . . On the 11th, we crossed the rivers Patowmack and Rapahannock, and lodged at Port Royal.

|

| 1757 Map of Maryland and Delaware Counties and the Southern Part of New Jersey |

On the way we had the company of a colonel of the militia, who appeared to be a thoughtful man. I took occasion to remark on the difference in general betwixt a people used to labour moderately for their living, training up their children in frugality and business, and those who live on the labour of slaves; the former, in my view, being the most happy life. He concurred in the remark, and mentioned the trouble arising from the untoward, slothful disposition of the negroes, adding that one of our labourers would do as much in a day as two of their slaves. I replied that free men, whose minds were properly on their business, found a satisfaction in improving, cultivating, and providing for their families; but negroes, labouring to support others who claim them as their property, and expecting nothing but slavery during life, had not the like inducement to be industrious.

After some further conversation I said, that men having power too often misapplied it; that though we made slaves of the negroes, and the Turks made slaves of the Christians, I believed that liberty was the natural right of all men equally. This he did not deny, but said the lives of the negroes were so wretched in their own country that many of them lived better here than there. I replied, "There is great odds in regard to us on what principle we act"; and so the conversation on that subject ended.

I may here add that another person, some time afterwards, mentioned the wretchedness of the negroes, occasioned by their intestine wars, as an argument in favour of our fetching them away for slaves.

To which I replied, if compassion for the Africans, on account of their domestic troubles, was the real motive of our purchasing them, that spirit of tenderness being attended to, would incite us to use them kindly, that, as strangers brought out of affliction, their lives might be happy among us.

And as they are human creatures, whose souls are as precious as ours, and who may receive the same help and comfort from the Holy Scriptures as we do, we could not omit suitable endeavours to instruct them therein; but that while we manifest by our conduct that our views in purchasing them are to advance ourselves, and while our buying captives taken in war animates those parties to push on the war and increase desolation amongst them, to say they live unhappily in Africa is far from being an argument in our favour.

. . . Soon after a Friend in company began to talk in support of the slave-trade, and said the negroes were understood to be the offspring of Cain, their blackness being the mark which God set upon him after he murdered Abel, his brother; that it was the design of Providence they should be slaves, as a condition proper to the race of so wicked a man as Cain was. Then another spake in support of what had been said.

To all which I replied in substance as follows: that Noah and his family were all who survived the flood, according to Scripture; and as Noah was of Seth's race, the family of Cain was wholly destroyed.

One of them said that after the flood Ham went to the land of Nod and took a wife; that Nod was a land far distant, inhabited by Cain's race, and that the flood did not reach it; and as Ham was sentenced to be a servant of servants to his brethren, these two families, being thus joined, were undoubtedly fit only for slaves.

I replied, the flood was a judgment upon the world for their abominations, and it was granted that Cain's stock was the most wicked, and therefore unreasonable to suppose that they were spared. As to Ham's going to the land of Nod for a wife, no time being fixed, Nod might be inhabited by some of Noah's family before Ham married a second time; moreover the text saith "That all flesh died that moved upon the earth" (Gen. vii. 21). I further reminded them how the prophets repeatedly declare "that the son shall not suffer for the iniquity of the father, but every one be answerable for his own sins."

I was troubled to perceive the darkness of their imaginations, and in some pressure of spirit said, "The love of ease and gain are the motives in general of keeping slaves, and men are wont to take hold of weak arguments to support a cause which is unreasonable. I have no interest on either side, save only the interest which I desire to have in the truth. I believe liberty is their right, and as I see they are not only deprived of it, but treated in other respects with inhumanity in many places, I believe He who is a refuge for the oppressed will, in His own time, plead their cause, and happy will it be for such as walk in uprightness before Him." And thus our conversation ended.One Biblical argument, widespread at a time when most people were prepared to accept the literal truth of the Bible, took the Africans to be the descendants of Canaan. In the biblical account of the peopling of the world by the sons of Noah after the Flood, Canaan was condemned to be "a servant of servants unto his brethren," because his father Ham had seen "the nakedness of his father"; and Canaan was believed to have settled in Africa. Noah's curse served conveniently to explain the color of the Africans' skin and their supposed "natural" indebtedness to the other nations of the world, particularly to the Europeans, the alleged descendants of Japheth, whom God had promised to "enlarge." This reading of the Book of Genesis merged easily into a medieval iconographic tradition in which devils were always depicted as black.

Woolman lived out the Friends' Peace Testimony by protesting the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the North American front of the Seven Years War between Great Britain and France. In 1755, he decided to oppose paying those colonial taxes that supported the war and urged tax resistance among fellow Quakers in the Philadelphia Meeting, even at a time when settlers on the frontier were being attacked by French and allied Native Americans. Some Quakers joined him in his protest, and the Meeting sent a letter on this issue to other groups.

Money being made current in our province for carrying on wars, and to be called in again by taxes laid on the inhabitants, my mind was often affected with the thoughts of paying such taxes; and I believe it right for me to preserve a memorandum concerning it.

I was told that Friends in England frequently paid taxes, when the money was applied to such purposes. I had conversation with several noted Friends on the subject, who all favoured the payment of such taxes; some of them I preferred before myself, and this made me easier for a time; yet there was in the depth of my mind a scruple which I never could get over; and at certain times I was greatly distressed on that account.

I believed that there were some upright-hearted men who paid such taxes, yet could not see that their example was a sufficient reason for me to do so, while I believe that the Spirit of truth required of me, as an individual, to suffer patiently the distress of goods, rather than pay actively. . . To do a thing contrary to my conscience appeared yet more dreadful.

When this exercise came upon me, I knew of none under the like difficulty; and in my distress I besought the Lord to enable me to give up all, that so I might follow Him wheresoever He was pleased to lead me. Under this exercise I went to our Yearly Meeting at Philadelphia in the year 1755; at which a committee was appointed of some from each Quarterly Meeting, to correspond with the meeting for sufferers in London; and another to visit our Monthly and Quarterly Meetings. After their appointment, before the last adjournment of the meeting, it was agreed that these two committees should meet together in Friends' school-house in the city, to consider some things in which the cause of truth was concerned. They accordingly had a weighty conference in the fear of the Lord; at which time I perceived there were many Friends under a scruple like that before mentioned.

As scrupling to pay a tax on account of the application hath seldom been heard of heretofore, even amongst men of integrity, who have steadily borne their testimony against outward wars in their time, I may therefore note some things which have occurred to my mind, as I have been inwardly exercised on that account. From the steady opposition which faithful Friends in early times made to wrong things then approved, they were hated and persecuted by men living in the spirit of this world, and suffering with firmness, they were made a blessing to the Church, and the work prospered.

. . . Friends thus met were not all of one mind in relation to the tax, which, to those who scrupled it, made the way more difficult. To refuse an active payment at such a time might be construed into an act of disloyalty, and appeared likely to displease the rulers not only here but in England; still there was a scruple so fixed on the minds of many Friends that nothing moved it. It was a conference the most weighty that ever I was at, and the hearts of many were bowed in reverence before the Most High. Some Friends of the said committees who appeared easy to pay the tax, after several adjournments, withdrew; others of them continued till the last.He did not refuse to quarter soldiers, but would not accept pay, explaining that he acted “in passive obedience to authority.”

Orders came to some officers in Mount Holly to prepare quarters for a short time for about one hundred soldiers. An officer and two other men, all inhabitants of our town, came to my house. The officer told me that he came to desire me to provide lodging and entertainment for two soldiers, and that six shillings a week per man would be allowed as pay for it. The case being new and unexpected, I made no answer suddenly, but sat a time silent, my mind being inward. I was fully convinced that the proceedings in wars are inconsistent with the purity of the Christian religion; and to be hired to entertain men, who were then under pay as soldiers, was a difficulty with me. I expected they had legal authority for what they did; and after a short time I said to the officer, If the men are sent here for entertainment, I believe I shall not refuse to admit them into my house, but the nature of the case is such that I expect I cannot keep them on hire. One of the men intimated that he thought I might do it consistently with my religious principles. To which I made no reply, believing silence at that time best for me. Though they spake of two, there came only one, who tarried at my house about two weeks, and behaved himself civilly. When the officer came to pay me, I told him I could not take pay, having admitted him into my house in a passive obedience to authority. I was on horseback when he spake to me, and as I turned from him, he said he was obliged to me; to which I said nothing; but, thinking on the expression, I grew uneasy; and afterwards, being near where he lived, I went and told him on what grounds I refused taking pay for keeping the soldier.Woolman's Journal revealed a moral awareness of the issues behind the French and Indian War. He understood that those who had gone out to live upon the western frontier had often done so to escape the usurious rents set by wealthy landowners. Woolman noted that the extending of English settlements meant that, for the Indians, "those wild beasts they chiefly depend on for their subsistence are not so plenty as they were," and, having been driven back by force, now have to pass over mountains, swamps, and barren deserts to bring their skins and furs to trade. And this led him "into a close, laborious inquiry whether I, as an individual, kept clear from all things which tended to stir up or were connected with war, whether in this land or Africa, and my heart was deeply concerned in future I might be in all things keep steadily to the pure Truth."

Woolman's views on slavery were not only unusual for whites in his day, but even unusual among his fellow Quakers. His method was moral persuasion backed up by consistent practice. In 1758, he preached a sermon against slavery in a rural community between Philadelphia and Baltimore. He was then taken to the home of Thomas Woodward for dinner. When Woolman determined that the "Negro servants" were actually slaves, he quietly slipped out of the house without saying a word. The owner's conscience was so troubled, the next morning he vowed to liberate his slaves.

Over time, and working on a personal level, he individually convinced many Quaker slaveholders to free their slaves. As Woolman traveled, when he accepted hospitality from a slaveholder, he insisted on paying the slaves for their work in attending him. He refused to be served with silver cups, plates, and utensils, as he believed that slaves in other regions were forced to dig such precious minerals and gems for the rich. He observed that some owners used the labor of their slaves to enjoy lives of ease, which he found to be the worst situation. He could condone those owners who treated their slaves gently, or worked alongside them. He also thought slavery was spiritually damaging to the slave owners.

I joined in company with my friends, John Sykes and Daniel Stanton, in visiting such as had slaves. Some, whose hearts were rightly exercised about them, appeared to be glad of our visit, but in some places our way was more difficult. I often saw the necessity of keeping down to that root from whence our concern proceeded, and have cause in reverent thankfulness humbly to bow down before the Lord who was near to me, and preserved my mind in calmness under some sharp conflicts, and begat a spirit of sympathy and tenderness in me towards some who were grievously entangled by the spirit of this world.

|

| Newport, Rhode Island |

Understanding that a large number of slaves had been imported from Africa into the town, and were then on sale by a member of our Society, my appetite failed; I grew outwardly weak . . .

The London Epistle for 1758, condemning the unrighteous traffic in men, was read, and the substance of it embodied in the discipline of the meeting; and the following query was adopted, to be answered by the subordinate meetings:

Are Friends clear of importing negroes, or buying them when imported; and do they use those well where they are possessed by inheritance or otherwise, endeavouring to train them up in principles of religion?At the close of the Yearly Meeting, John Woolman requested those members of the Society who held slaves to meet with him in the chamber of the house for worship, where he expressed his concern for the well-being of the slaves, and his sense of the iniquity of the practice of dealing in, or holding them as property.

In 1759, Woolman wrote a second letter, sometimes called the Pacifist Epistle. In response to the draft, he emphasized principled objection, decrying objectors who merely “pretend scruple of conscience.”

Woolman gave up the wearing of dyed clothing, both because they represented what he would call a 'superfluity', and because the dyes were made from indigo, a product of slave labor. He ate no sugar for the same reasons.

Slave traders were excluded from the Society of Friends in 1761 by American Quakers, despite the fact that many Quakers continued to own slaves.

|

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

In 1761, Woolman was in Philadelphia on a visit to some Friends who had slaves, to convince them to free the slaves. There he met a group of Indians from Wyalusing. He writes that:

in conversation with them by an interpreter, as also by observations on their countenance and conduct, I believed some of them were measurably acquainted with that divine power which subjects the rough and froward will of creature; and at times I felt inward drawings toward a visit to that place, of which I told none except my dear wife until it came to some ripeness.

In June 1763, John Woolman left his home in Mount Holly to travel on horseback to Wyalusing, Pennsylvania, because

[I had for] … many years felt love in my heart toward the natives of this land who dwell far back in the wilderness, whose ancestors were the owners and possessors of the land where we dwell, and who for a very small consideration assigned their inheritance to us…It was a war zone. The night before Woolman left home, a delegation of Friends rode out from Philadelphia and roused him out of bed to try to talk him out of going at that time. They brought fresh news of hostilities increasing on the frontier. Woolman went the next morning, knowing this, and also clear that he was in God’s care. His actions would be for the good, even if he did not survive. One week into the journey, on a rainy morning, sitting in his tent on swampy ground, he asked himself why he was there. He wrote this answer:

Love was the first motion, and then a concern arose to spend some time with the Indians, that I might feel and understand their life and the spirit they live in, if haply I might receive some instruction from them, or they be in any degree helped forward by my following the leadings of truth amongst them.

And as it pleased the Lord to make way for my going at a time when the troubles of war were increasing, and when by reason of much wet weather travelling was more difficult than was usual at that season, I looked upon it as a more favorable opportunity to season my mind and bring me into a nearer sympathy with them.He was traveling with his friend Benjamin Parvin and four Native American guides, one man and three women, whom he had met one month earlier while they were in Philadelphia on business. Woolman had agreed to join with them as companions for their return. In addition to the six who traveled together to Wyalusing, various Quakers housed fed the group. Indians also offered food, shelter and assistance. During the journey, further news arrived of forts taken, settlers killed and scalped, Indian families relocating and warriors on the move.

In this lonely journey I did this day greatly bewail the spreading of a wrong spirit, believing that the prosperous, convenient situation of the English requires a constant attention to divine love and wisdom, to guide and support us in a way answerable to the will of that good, gracious and almighty Being who hath an equal regard to all mankind.

And here luxury and covetousness, with the numerous oppressions and other evils attending them, appeared very afflicting to me, and I felt in that which is immutable that the seeds of great calamity are sown and growing fast on this continent.

Between the English settlements and Wehaloosing we had only a narrow path, which in many places is much grown up with bushes, and interrupted by abundance of trees lying across it. These, together with the mountain swamps and rough stones, make it a difficult road to travel, and the more so because rattlesnakes abound here, of which we killed four.

People who have never been in such places have but an imperfect idea of them; and I was not only taught patience, but also made thankful to God, who thus led about and instructed me, that I might have a quick and lively feeling of the afflictions of my fellow-creatures, whose situation in life is difficult.Woolman yearned for his countrymen to turn away from luxury and greed before it was too late, and to follow Christ’s example by living simply and abundantly in equality and love.

At our Yearly Meeting at Philadelphia this day, John Smith, of Marlborough, aged upwards of eighty years, a faithful minister, though not eloquent, stood up in our meeting of ministers and elders, and appearing to be under a great exercise of spirit, informed Friends in substance as follows: "That he had been a member of our Society upwards of sixty years, and he well remembered that, in those early times, Friends were a plain, lowly-minded people, and that there was much tenderness and contrition in their meetings. That, at twenty years from that time, the Society increasing in wealth and in some degree conforming to the fashions of the world, true humility was less apparent, and their meetings in general were not so lively and edifying. That at the end of forty years many of them were grown very rich, and many of the Society made a specious appearance in the world; that wearing fine costly garments, and using silver and other watches, became customary with them, their sons, and their daughters.

. . . Having hired a man to work, I perceived in conversation with him that he had been a soldier in the late war on this continent; and he informed me in the evening, in a narrative of his captivity among the Indians, that he saw two of his fellow-captives tortured to death in a very cruel manner.

This relation affected me with sadness, under which I went to bed; and the next morning, soon after I awoke, a fresh and living sense of divine love overspread my mind, in which I had a renewed prospect of the nature of that wisdom from above which leads to a right use of all gifts, both spiritual and temporal, and gives content therein. Under a feeling thereof, I wrote as follows: --

"Hath He who gave me a being attended with many wants unknown to brute creatures given me a capacity superior to theirs, and shown me that a moderate application to business is suitable to my present condition; and that this, attended with His blessing, may supply all my outward wants while they remain within the bounds He hath fixed, and while no imaginary wants proceeding from an evil spirit have any place in me?

. . . Doth pride lead to vanity? Doth vanity form imaginary wants? Do these wants prompt men to exert their power in requiring more from others than they would be willing to perform themselves, were the same required of them?

Do these proceedings beget hard thoughts? Do hard thoughts, when ripe, become malice? Does malice, when ripe, become revengeful, and in the end inflict terrible pains on our fellow-creatures and spread desolations in the world?

. . . Remember then thy station as being sacred to God. Accept of the strength freely offered to thee, and take heed that no weakness in conforming to unwise, expensive, and hard-hearted customs, gendering to discord and strife, be given way to.Woolman's final journey was to England in 1772. During the voyage he stayed in steerage and spent time with the crew, rather than in the better accommodations in cabins enjoyed by some passengers. He attended the British London Yearly Meeting, and the Friends resolved to include an anti-slavery statement in their Epistle.

Stage-coaches frequently go upwards of one hundred miles in twenty-four hours; and I have heard Friends say in several places that it is common for horses to be killed with hard driving, and that many others are driven till they grow blind. Post-boys pursue their business, each one to his stage, all night through the winter. Some boys who ride long stages suffer greatly in winter nights, and at several places I have heard of their being frozen to death.

So great is the hurry in the spirit of this world, that in aiming to do business quickly and to gain wealth, the creation at this day doth loudly groan.

In England he visited the Quarterly and subordinate meetings of Friends in seven counties, and wrote essays upon "Loving our Neighbours," "A Sailor's Life," and "Silent Worship."

His last public testimony was in the York Meeting on behalf of the poor and enslaved.

Woolman contracted smallpox, and was cared for at the home of Thomas Priestman. a tanner on Marygate Lane. Aoccording to Thomas P. Slaughter, author of The Beautiful Soul of John Woolman, on September 29, Woolman made plans for his funeral:

He was buried in in the Friends' Burial Ground Bishophill in York on October 9, 1772.

A plaque at Littlegarth, off Marygate Lane in York, marks where he stayed and died.

Woolman contracted smallpox, and was cared for at the home of Thomas Priestman. a tanner on Marygate Lane. Aoccording to Thomas P. Slaughter, author of The Beautiful Soul of John Woolman, on September 29, Woolman made plans for his funeral:

He was concerned that too much would be spent on it. The Friends around him reassured him that they would bear the costs, but he would not accept this gift. He instructed them to sell all the clothes he had brought on the trip and spend no more than the proceeds to bury him. He also vetoed an oak coffin, reasoning that it was a wood better used for other purposes than just to rot in the ground.They encouraged Woolman to eat, but it was difficult:

In the night, a young woman having given him something to drink, he said, "My child, thou seemest very kind to me, a poor creature; the Lord will reward thee for it." . . . Being asked if he could take a little nourishment, after some pause he replied, "My child, I cannot tell what to say to it; I seem nearly arrived where my soul shall have rest from all its troubles."John Woolman passed away on October 7, 1772. He died less than two weeks before his 52nd birthday.

|

| Chair in which John Woolman died |

He was buried in in the Friends' Burial Ground Bishophill in York on October 9, 1772.

A plaque at Littlegarth, off Marygate Lane in York, marks where he stayed and died.

The Journal of John Woolman was published posthumously in 1774 by Joseph Crukshank, a Philadelphia Quaker printer. It is considered a prominent American spiritual work and is the longest-published book in the history of North America other than the Bible, having been continuously in print since 1774.

Woolman did not succeed in eradicating slavery within the Society of Friends in colonial America; however, his personal efforts helped change Quaker viewpoints. In 1775, Quakers played a dominant role in the formation of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, the first antislavery society in America. The Pennsylvania Gradual Abolition Act of 1780 was the first emancipation statute in the United States. After the American Revolutionary War and independence, in 1790 the Pennsylvania Society of Friends petitioned the United States Congress for the abolition of slavery. While unsuccessful at the national level, Quakers contributed to Pennsylvania's abolition of slavery.

In addition, in the first two decades after the war, they were active together with Methodist and Baptist preachers in the Upper South in persuading many slaveholders to manumit their slaves. The percentage of free people of color rose markedly during those decades, for instance, from less than one to nearly ten percent in Virginia.

After the Revolutionary War, many northern states rapidly passed laws to abolish slavery, but New Jersey did not pass abolish it until 1804, and then in a process of gradual emancipation similar to that of New York. However, in New Jersey, some slaves were held as late as 1865. (In New York, they were all freed by 1827.) The law made African Americans free at birth, but required children born to slave mothers to serve lengthy apprenticeships as a type of indentured servant until early adulthood for the masters of their slave mothers. New Jersey was the last of the Northern states to abolish slavery completely. The last 16 slaves in New Jersey were freed in 1865 by the Thirteenth Amendment.

Woolman did not succeed in eradicating slavery within the Society of Friends in colonial America; however, his personal efforts helped change Quaker viewpoints. In 1775, Quakers played a dominant role in the formation of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, the first antislavery society in America. The Pennsylvania Gradual Abolition Act of 1780 was the first emancipation statute in the United States. After the American Revolutionary War and independence, in 1790 the Pennsylvania Society of Friends petitioned the United States Congress for the abolition of slavery. While unsuccessful at the national level, Quakers contributed to Pennsylvania's abolition of slavery.

In addition, in the first two decades after the war, they were active together with Methodist and Baptist preachers in the Upper South in persuading many slaveholders to manumit their slaves. The percentage of free people of color rose markedly during those decades, for instance, from less than one to nearly ten percent in Virginia.

|

| New Jersey Advertisements for Runaway Slaves July 1781 |

The John Woolman Memorial in Mount Holly, New Jersey is located near one of his former orchards. The memorial and museum is located in a brick house built between 1771-1783, reportedly for Woolman's daughter and her husband.

|

| The John Woolman Memorial in Mount Holly, New Jersey |

"When we remember that all nations are of one blood; that in this world we are but sojourners; that we are subject to the like afflictions and infirmities of the body, the like disorders and frailties in mind, the like temptations, the same death and the same judgment; and that the All-wise Being is judge and Lord over us all, it seems to raise an idea of a general brotherhood and a disposition easy to be touched with a feeling of each other’s afflictions.

But when we forget these things and look chiefly at our outward circumstances, in this and some ages past, constantly retaining in our minds the distinction betwixt us and them with respect to our knowledge and improvement in things divine, natural, and artificial, our breasts being apt to be filled with fond notions of superiority, there is danger of erring in our conduct toward them.

. . . To consider mankind otherwise than brethren, to think favours are peculiar to one nation and exclude others, plainly supposes a darkness in the understanding.

For as God’s love is universal, so where the mind is sufficiently influenced by it, it begets a likeness of itself and the heart is enlarged towards all men. Again, to conclude a people froward, perverse, and worse by nature than others (who ungratefully receive favours and apply them to bad ends), this will excite a behavior toward them unbecoming the excellence of true religion."

~ John Woolman