Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, at the Clay homestead in Hanover County, Virginia. Henry was the seventh of nine children of the Reverend John Clay and Elizabeth Hudson Clay. The Revolutionary War had begun two years ealier, and he was three years old when he watched the British troops ransack his family home.

His father, a Baptist minister nicknamed "Sir John," died in 1781, four years after Henry's birth. At the time of his death, John Clay owned more than 22 slaves, making him part of the planter class in Virginia (those men who owned 20 or more slaves). He father left two slaves to each of his sons, and his widow received 18 slaves and 464 acres of land.

Ten years later, Elizabeth Clay married Capt. Henry Watkins, who was an affectionate stepfather. Henry Watkins moved the family to Richmond, Virginia. Elizabeth had seven more children with Watkins, bearing a total of sixteen.

His stepfather secured employment for Henry in the office of the Virginia Court of Chancery, where he displayed an aptitude for law. There he became friends with George Wythe. Hampered by a crippled hand, Wythe chose Clay as his secretary.

His father, a Baptist minister nicknamed "Sir John," died in 1781, four years after Henry's birth. At the time of his death, John Clay owned more than 22 slaves, making him part of the planter class in Virginia (those men who owned 20 or more slaves). He father left two slaves to each of his sons, and his widow received 18 slaves and 464 acres of land.

Ten years later, Elizabeth Clay married Capt. Henry Watkins, who was an affectionate stepfather. Henry Watkins moved the family to Richmond, Virginia. Elizabeth had seven more children with Watkins, bearing a total of sixteen.

His stepfather secured employment for Henry in the office of the Virginia Court of Chancery, where he displayed an aptitude for law. There he became friends with George Wythe. Hampered by a crippled hand, Wythe chose Clay as his secretary.

|

| George Wythe |

Henry Clay was born six years before the Revolutionary War ended, and died nine years before the Civil War began.

|

| Clay's Law Office in Lexington, Kentucky |

After beginning his law career, Clay married Lucretia Hart on April 11, 1799, at the Hart home in Lexington, Kentucky. They were married for more than 50 years and had eleven children (six daughters and five sons). Seven of Clay's children died before him and his wife. By 1835 all six daughters had died of varying causes, two when very young, two as children, the other two as young women: from whooping cough, yellow fever, and complications of childbirth.

Clay was a second cousin of Cassius Clay, who became an abolitionist in Kentucky.

|

| Cassius Marcellus Clay |

In 1803, Clay was elected to serve as the representative of Fayette County in the Kentucky General Assembly. As a legislator, Clay advocated a liberal interpretation of the state's constitution and initially the gradual emancipation of slavery in Kentucky, although the political realities of the time forced him to abandon that position.

In 1806 the Kentucky legislature elected him to the United States Senate. On December 29, 1806, Clay was sworn in as senator, serving for less than one year that first time. When elected by the legislature, Clay was below the constitutionally required age of thirty; his age did not appear to have been noticed. Three months and 17 days into his Senate service, he reached the age of eligibility.

When Clay returned to Kentucky in 1807, he was elected the Speaker of the state House of Representatives.

On January 3, 1809, Clay introduced a resolution to require members to wear homespun suits rather than those made of imported British cloth. Two members voted against the measure: one was Humphrey Marshall, an "aristocratic lawyer who possessed a sarcastic tongue." Clay and Marshall nearly came to blows on the Assembly floor, and Clay challenged Marshall to a duel. The duel took place on January 9. They each had three turns. Clay grazed Marshall once, just below the chest. Marshall hit Clay once in the thigh.

|

| Humphrey Marshall |

In the summer of 1811, Clay was elected to the United States House of Representatives. He was chosen Speaker of the House on the first day of his first session, something never done before or since. During the fourteen years following his first election, he was re-elected five times to the House and to the speakership.

Like other Southern Congressmen, Clay took slaves to Washington, D.C. to work in his household. They included Aaron and Charlotte Dupuy, their son Charles and daughter Mary Ann.

Before Clay's election as Speaker of the House, the position had been that of a rule enforcer and mediator. Clay made the position one of political power second only to the President of the United States. He immediately appointed members of the War Hawk faction (of which he was the "guiding spirit") to all the important committees, effectively giving him control of the House. This was a singular achievement for a 34-year-old House freshman.

Before Clay's election as Speaker of the House, the position had been that of a rule enforcer and mediator. Clay made the position one of political power second only to the President of the United States. He immediately appointed members of the War Hawk faction (of which he was the "guiding spirit") to all the important committees, effectively giving him control of the House. This was a singular achievement for a 34-year-old House freshman.

Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun helped to pass the Tariff of 1816 as part of the national economic plan Clay called "The American System". It was designed to allow the fledgling American manufacturing sector, largely centered on the eastern seaboard, to compete with British manufacturing through the creation of tariffs. After the conclusion of the War of 1812, British factories were overwhelming American ports with inexpensive goods. To persuade voters in the western states to support the tariff, Clay advocated federal government support for improvement to infrastructure, principally roads and canals. These improvements would be financed by the tariff and by sale of the public lands, prices for which would be kept high to generate revenue.

|

| John Calhoun |

Henry Clay helped establish and became president in 1816 of the American Colonization Society (ACS), a group that wanted to establish a colony for free American blacks in Africa. It founded Monrovia, in what became Liberia, for that purpose. The group was made up of both abolitionists from the North, who wanted to end slavery, and slaveholders, who wanted to deport free blacks to reduce what they considered a threat to the stability of slave society. On the "amalgamation" of the black and white races, Clay said that "The God of Nature, by the differences of color and physical constitution, has decreed against it." Clay presided at the founding meeting of the ACS on December 21, 1816, at the Davis Hotel in Washington, D.C.

He was admired by a young Abraham Lincoln, who referred to Clay as "my beau ideal of a statesman." Although Lincoln is not known to have ever met Henry Clay, there can be little doubt of the profound impact Clay had on him. Lincoln often quoted Clay in speeches in order to reinforce his own ideas or, at times, even in place of them. In the great debates with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln quoted Clay no fewer than 41 times. In 1862, Lincoln appointed Henry Clay’s son Thomas to the posts of Minister to Nicaragua and ultimately to Honduras for little more reason than that he was Henry Clay’s son. In 1864, Henry Clay’s son John sent Lincoln a snuff box owned by his father.

|

| Abraham Lincoln as a young congressman |

Clay was appointed Secretary of State by President John Quincy Adams in 1825.

.jpg) |

| Decatur House, Washington, D.C. |

The jury ruled against Dupuy, deciding that any agreement with her previous master Condon did not bear on Clay. Because Dupuy refused to return voluntarily to Kentucky, Clay had his agent arrest her. She was imprisoned in Alexandria, Virginia before Clay arranged for her transport to New Orleans, where he placed her with his daughter and son-in-law Martin Duralde. Mary Ann Dupuy was sent to join her mother, and they worked as domestic slaves for the Duraldes for another decade.

In 1840 Henry Clay finally gave Charlotte and her daughter Mary Ann Dupuy their freedom. He kept her son Charles Dupuy as a personal servant, frequently citing him as an example of how well he treated his slaves. Clay granted Charles Dupuy his freedom in 1844.

|

| Charles Dupuy |

|

| Aron Dupuy |

After the election of Andrew Jackson as president in 1829, Clay led the opposition to Jackson's policies. His supporters included the National Republicans, who were beginning to identify as "Whigs" in honor of ancestors during the Revolutionary War. They opposed the "tyranny" of Jackson, as their ancestors had opposed the tyranny of King George III.

|

| Andrew Jackson |

|

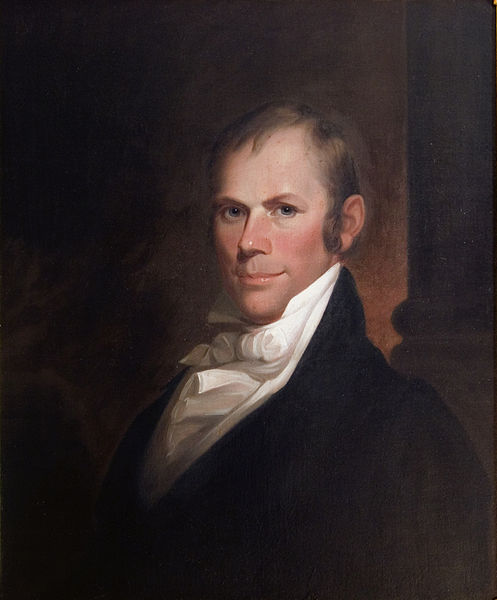

| Henry Clay |

|

| William Henry Harrison |

|

| James Polk |

In 1844, Clay was nominated by the Whigs against James Polk, the Democratic candidate. Clay lost in part due to national sentiment in favor of Polk's campaign.to settle the northern boundary of the United States with Canada, then under the control of the British Empire. Clay opposed admitting Texas as a state because he believed it would reawaken the slavery issue and provoke Mexico to declare war. Polk took the opposite view, supported by most of the public, especially in the Southern United States. The election was close; New York's 36 electoral votes proved the difference, and went to Polk by a slim 5,000 vote margin.

|

| Clay Campaign Banner, 1844 |

|

| Death of Lt. Henry Clay, Jr. in Mexican American War |

|

| Jefferson Davis |

|

| Zachary Taylor |

|

| Henry and Lucretia Clay on their 50th Wedding Anniversary, 1849 |

During his term, the controversy over the expansion of slavery in new lands had reemerged with the addition of the lands ceded to the United States by Mexico in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War. David Wilmot, a Northern congressman, had proposed preventing the extension of slavery into any of the new territory in a proposal referred to as the "Wilmot Proviso".

|

| David Wilmot |

- Admission of California as a free state, ending the balance of free and slave states in the senate

- Organization of the Utah and New Mexico territories without any slavery provisions, giving the right to determine whether to allow slavery to the territorial populations

- Prohibition of the slave trade, but not the ownership of slaves, in the District of Columbia

- A more stringent Fugitive Slave Act

- Establishment of boundaries for the state of Texas in exchange for federal payment of Texas's ten million dollar debt.

- A declaration by Congress that it did not have the authority to interfere with the interstate slave trade.

The Omnibus bill, despite Clay's efforts, failed in a crucial vote on July 31 with the majority of his Whig Party opposed. He announced on the Senate floor the next day that he intended to persevere and pass each individual part of the bill.

|

| Stephen Douglas |

Clay was given much of the credit for the Compromise's success. It quieted the controversy between Northerners and Southerners over the expansion of slavery, and delayed secession and civil war for another decade.

Senator Henry Foote of Mississippi, later said, "Had there been one such man in the Congress of the United States as Henry Clay in 1860–'61 there would, I feel sure, have been no civil war."

He died of tuberculosis at the age of 75.

|

| "Death of Henry Clay", with his son, Thomas, sitting at his bedside |

|

| Telegraph from Thomas Clay to family: "Our Father is no more" |

Following the Senate funeral on June 30, citizens from Washington, D.C., and all the surrounding towns gathered in the streets to watch as a gilded hearse transported Clay's remains to the railroad depot. The elaborately decorated coffin, along with six designated Congressional representatives, Clay family members, and other dignitaries, departed at 4:00 p.m. on a special train to Baltimore. Baltimore officials met Clay's body early on the morning of July 1, and a procession through the city followed at noon. The Baltimore Weekly Sun declared that all businesses closed, and "The city presented a gloomy and mournful aspect … The bells of all the churches, engine houses and other places were tolled … the sidewalks completely jammed up with men, women and children, all eager to take a last look at the remains of the great American statesman." Clay lay in repose on a specially constructed catafalque in the rotunda of the Exchange Building until the next day, as thousands of people filed by to see his face, which was exposed through a glass window in his metal coffin.

On July 2, the delegation left Baltimore with Clay's body on another train, and passed through Wilmington, Delaware, where his coffin was again unloaded and placed in repose at City Hall. The Congressional committee, augmented by town committees from both Baltimore and Wilmington, then accompanied the body back on the train to Philadelphia, where they arrived at 9:00 p.m. Clay's remains were paraded for two hours through Philadelphia in a torch-lit procession to Independence Hall, which "was brilliantly lit up with bonfires, and [where] thousands of ladies had congregated inside its walls to witness the passage of the procession." Clay's coffin was placed on a cenotaph in the center of Independence Hall, and crowds of people flocked to see it through the night.

When Clay's boat arrived at Castle Garden in New York City on the afternoon of July 3, thousands of people were on hand to greet it, and "an immense military and civic procession was then formed, which escorted the remains to the City Hall" in an open hearse. New York City, long a hotbed of support for Clay and home of the Whig Clay Festival Association, which had organized public birthday celebrations for Clay, tried to outdo all the previous cities in the lavish honors it paid to Clay. The procession accompanying Clay's remains through New York streets lasted more than three hours as hotels, theaters, "The City Hall, Broadway, Chatham Street, and Park Row were literally shrouded in mourning." New Yorkers paid respects to Clay as he lay in state at City Hall overnight, although visitors were unable to gaze upon his face. The face plate was not removed from his coffin because of the hot weather that threatened to damage his remains before they reached Kentucky.

All day on July 4, "great numbers of citizens" continued to file past his coffin, which was displayed with huge floral tributes and a sign reading "A Nation Mourns Its Loss." Since Independence Day fell on a Sunday, clergy all over town preached sermons that wove together a commemoration of the national holiday and a eulogy for Clay.

Clay's funeral delegation departed New York City on the morning of July 5 to travel up the Hudson River aboard the steamer Santa Claus. At Albany, Clay's coffin was accompanied by fire companies bearing torches to the New York state capitol, where guards attended the body overnight. The next morning, Clay's body traveled west through Schenectady, Utica, Rome, Syracuse, and Rochester to Buffalo, where he was loaded directly on the Erie steamer Buckeye State, which carried him overnight to Ohio.

Clay's funeral delegation departed New York City on the morning of July 5 to travel up the Hudson River aboard the steamer Santa Claus. At Albany, Clay's coffin was accompanied by fire companies bearing torches to the New York state capitol, where guards attended the body overnight. The next morning, Clay's body traveled west through Schenectady, Utica, Rome, Syracuse, and Rochester to Buffalo, where he was loaded directly on the Erie steamer Buckeye State, which carried him overnight to Ohio.

On the morning of July 7, Clay's remains arrived in Cleveland and then moved via rail through Columbus to Cincinnati, arriving on July 8. In Cincinnati, "a large procession of military, Free Masons, Odd Fellows, Firemen and citizens, conducted the remains through a portion of the city" for more than an hour as over 10,000 people gathered outside heavily draped public buildings. After the procession through Cincinnati, Clay's remains were placed aboard the U.S. mail boat Ben Franklin bound for Louisville. Onlookers gathered on the river's banks to catch a glimpse of Clay's coffin, and several papers emphasized the touching scene as the boat passed Rising Sun, Indiana, where "grouped together were some 200 ladies, one of whom was dressed in the deepest mourning, attended by the rest dressed in white with armlets of black ribbon."

On July 9, Clay's body made its final journey via rail from Louisville through Frankfort to Lexington.

|

| Funeral Procession in Lexington |

Clay's headstone reads: "I know no North — no South — no East — no West."

After Clay’s death, a local committee was formed to oversee the construction of “a national monument of colossal proportions” in the Lexington Cemetery.

By the time of his death, his only surviving sons were James Brown Clay and John Morrison Clay, who inherited the estate and took portions for their use.

|

| James Brown Clay |

No comments:

Post a Comment