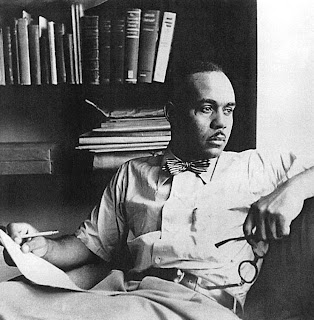

Ralph Ellison, named after Ralph Waldo Emerson, was born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, to Lewis Alfred Ellison and Ida Millsap. He was the grandson of former slaves. Lewis Alfred Ellison, a small-business owner and a construction foreman. Lewis, who loved children and read books voraciously, worked as an ice and coal deliverer. He died from a work-related accident when Ellison was only three years old. His mother Ida then raised Ralph and younger brother Herbert by herself, working a variety of jobs to make ends meet. Many years later, Ellison would find out that his father hoped he would grow up to be a poet.

Ellison was born about 50 years after the end of the Civil War.

In 1936, Ellison went to New York over the summer with the intent of earning enough money to pay for his college expenses, but ended up relocating. Ellison had every intention of returning to Tuskegee. But the Great Depression prevented him from earning the needed funds. He studied sculpture and photography. He made acquaintance with the artist Romare Bearden. Perhaps Ellison's most important contact would be with the author Richard Wright, with whom he would have a long and complicated relationship. After Ellison wrote a book review for Wright, Wright encouraged Ellison to pursue a career in writing, specifically fiction. The first published story written by Ellison was a short story entitled "Hymie's Bull," a story inspired by Ellison's hoboing on a train with his uncle to get to Tuskegee.

Wright was then openly associated with the Communist Party and Ellison was publishing and editing for communist publications, although his "affiliation was quieter," according to historian Carol Polsgrove in Divided Minds. Both Wright and Ellison lost their faith in the Communist Party during World War II when they felt the party had betrayed African Americans and replaced Marxist class politics with social reformism. In a letter to Wright, August 18, 1945, Ellison poured out his anger with party leaders: "If they want to play ball with the bourgeoisie they needn't think they can get away with it. ... Maybe we can't smash the atom, but we can, with a few well chosen, well written words, smash all that crummy filth to hell."

In the wake of this disillusion, Ellison began writing Invisible Man, a novel that was, in part, his response to the party's betrayal.

|

| Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison |

World War II was nearing its end when Ellison, reluctant to serve in the segregated army, chose merchant marine service over the draft. In 1946 he married his second wife, Fanny McConnell. She worked as a photographer to help sustain Ellison. From 1947 to 1951 he earned some money writing book reviews, but spent most of his time working on Invisible Man. Fanny also helped type Ellison's longhand text and assisted her husband in editing the typescript as it progressed.

Published in 1952, Invisible Man explores the theme of man’s search for his identity and place in society, as seen from the perspective of an unnamed black man in the New York City of the 1930s. In contrast to his contemporaries such as Richard Wright and James Baldwin, Ellison created characters that are dispassionate, educated, articulate and self-aware. Through the protagonist, Ellison explores the contrasts between the Northern and Southern varieties of racism and their alienating effect.

The narrator is "invisible" in a figurative sense, in that "people refuse to see" him, and also experiences a kind of dissociation. The novel, with its treatment of taboo issues such as incest and the controversial subject of communism, won the 1953 U.S. National Book Award for Fiction.

Ralph and Fanny Ellsion lived together in an apartment on Riverside Drive in New York City until Ellison died on April 16, 1994, of pancreatic cancer, and was buried at Trinity Church Cemetery in New York City.  |

| Sculpture memorial to Ralph Ellison and "Invisible Man" |

No comments:

Post a Comment