The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was one of the largest political rallies for human rights in United States history. It called for civil and economic rights for African Americans.

It took place in Washington, D.C. on Wednesday, August 28, 1963. Martin Luther King, Jr., standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, delivered his historic "I Have a Dream" speech advocating racial harmony during the march.

|

| Crowd around Lincoln Memorial |

The march is widely credited with helping to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The march was organized by a group of civil rights, labor, and religious organizations, under the theme "jobs, and freedom".

The march was organized by a group of civil rights, labor, and religious organizations, under the theme "jobs, and freedom".

|

| Bayard Rustin (left) and Cleveland Robinson (right), organizers of the March, on August 7, 1963 |

Earlier efforts to organize a demonstration included the March on Washington Movement of the 1940s. A. Philip Randoph was president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, president of the Negro American Labor Council, and vice president of the AFL-CIO; he was a key instigator in 1941. With Bayard Rustin, Randolph called for 10,000 black workers to march on Washington, in protest of discriminatory hiring by U.S. military contractors. Faced with a mass march scheduled for July 1, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 on June 25. The order established the Committee on Fair Employment Practice and banning discriminatory hiring in the defense industry. Randolph called off the March.

Randolph and Rustin continued to envision large marches during the 1940s, but all were called off. Their Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, held at the Lincoln Memorial on May 17, 1957, featured key leaders including Adam Clayton Powell, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Roy Wilkins. Mahalia Jackson performed.

The 1963 march was an important part of the rapidly expanding Civil Rights Movement, which involved demonstrations and nonviolent direct action across the United States.

1963 also marked the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln.

Randolph and Rustin began planning the march in December 1962. They envisioned two days of protest, including sit-ins and lobbying followed by a mass rally at the Lincoln Memorial. They wanted to focus on joblessness and to call for a public works program that would employ blacks. In early 1963 they called publicly for "a massive March on Washington for jobs". As they negotiated with other leaders, they expanded their stated objectives to "Jobs and Freedom" to acknowledge the agenda of groups that focused more on civil rights.

Randolph and Rustin began planning the march in December 1962. They envisioned two days of protest, including sit-ins and lobbying followed by a mass rally at the Lincoln Memorial. They wanted to focus on joblessness and to call for a public works program that would employ blacks. In early 1963 they called publicly for "a massive March on Washington for jobs". As they negotiated with other leaders, they expanded their stated objectives to "Jobs and Freedom" to acknowledge the agenda of groups that focused more on civil rights.

|

| James Farmer |

|

| Roy Wilkins |

Wilkins and Young initially objected to Rustin as a leader for the march, because he was a homosexual, had been affiliated with the Communist Party in the 1930s, and as a Quaker had been a Conscientious Objector during World War II. They eventually accepted Rustin as deputy organizer, on the condition that Randolph act as lead organizer and manage any political fallout.

Mobilization and logistics were administered by Rustin, a civil rights veteran and organizer of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, the first of the Freedom Rides to test the Supreme Court ruling that banned racial discrimination in interstate travel.

Rustin was a long-time associate of both Randolph and King. With Randolph concentrating on building the march's political coalition, Rustin built and led the team of 200 activists and organizers who publicized the march and recruited the marchers, coordinated the buses and trains, provided the marshals, and set up and administered all of the logistic details of a mass march in the nation's capital.

March organizers themselves disagreed over the purpose of the march. The NAACP and Urban League saw it as a gesture of support for a civil rights bill. Randolph, King, and the SCLC saw it as a way of raising both civil rights and economic issues to national attention. SNCC and CORE saw it as a way of challenging and condemning the Kennedy administration's inaction and lack of support for civil rights for African Americans.

Despite their disagreements, the group came together on a set of goals:

March organizers themselves disagreed over the purpose of the march. The NAACP and Urban League saw it as a gesture of support for a civil rights bill. Randolph, King, and the SCLC saw it as a way of raising both civil rights and economic issues to national attention. SNCC and CORE saw it as a way of challenging and condemning the Kennedy administration's inaction and lack of support for civil rights for African Americans.

Despite their disagreements, the group came together on a set of goals:

- Passage of meaningful civil rights legislation.

- Immediate elimination of school segregation.

- A program of public works, including job training, for the unemployed.

- A Federal law prohibiting discrimination in public or private hiring.

- A $2-an-hour minimum wage nationwide.

- Withholding Federal funds from programs that tolerate discrimination.

- Enforcement of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution by reducing congressional representation from States that disenfranchise citizens.

- A broadened Fair Labor Standards Act to currently excluded employment areas.

- Authority for the Attorney General to institute injunctive suits when constitutional rights are violated.

Although in years past Randolph had supported "Negro only" marches, partly to reduce the impression that the civil rights movement was dominated by white communists, organizers in 1963 agreed that whites and blacks marching side by side would create a more powerful image.

The Kennedy Administration cooperated with the organizers in planning the March, and one member of the Justice Department was assigned as a full-time liaison. Chicago and New York City (as well as some corporations) agreed to designate August 28 as "Freedom Day" and give workers the day off.

To avoid being perceived as radical, organizers rejected support from Communist groups. However, some politicians claimed that the March was Communist-inspired, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) produced numerous reports suggesting the same. In the days before August 28, the FBI called celebrity backers to inform them of the organizers' communist connections and advising them to withdraw their support. When William Sullivan produced a lengthy report on August 23 suggesting that Communists had failed to appreciably infiltrate the civil rights movement, FBI Director J.Edgar Hoover rejected its contents.

Strom Thurmond, North Carolina senator, launched a prominent public attack on the March as Communist, and singled out Rustin in particular as a Communist and a gay man.

Organizers worked out of a building at West 130th St. and Lenox in Harlem, New York City. They promoted the march by selling buttons, featuring two hands shaking, the words "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom", a union bug, and the date August 28, 1963. By August 2 they had distributed 42,000 of the buttons.

Despite the protests of organizer Anna Arnold Hedgeman, no women were scheduled to speak at the March. Male organizers attributed this omission to the "difficulty of finding a single woman to speak without causing serious problems vis-à-vis other women and women's groups". Hedgeman read a statement at an August 16 meeting, charging:

I think really the main difference between somebody like Bayard Rustin and Senator Thurmond, Bayard came out of a tradition of authenticity, of openness. He was raised as a Quaker by his grandmother. And part of the Quaker values and tradition is, you know, being honest, searching for the truth and not really having secrets. And I think, as we all know, Senator Thurmond had plenty of secrets of his own, but he—and he was not quite so open about them.

~ Walter Naegle

|

| Bayard Rustin showing route of the march on map |

Despite the protests of organizer Anna Arnold Hedgeman, no women were scheduled to speak at the March. Male organizers attributed this omission to the "difficulty of finding a single woman to speak without causing serious problems vis-à-vis other women and women's groups". Hedgeman read a statement at an August 16 meeting, charging:

In light of the role of Negro women in the struggle for freedom and especially in light of the extra burden they have carried because of the castration of our Negro men in this culture, it is incredible that no woman should appear as a speaker at the historic March on Washington Meeting at the Lincoln Memorial.

As the march was being planned, activists across the country received bomb threats at their homes and in their offices. The Los Angeles Times received a message saying its headquarters would be bombed unless it printed a message calling the president a "Nigger Lover". Five airplanes were grounded on the morning of August 28 due to bomb threats. A man in Kansas City telephoned the FBI to say he would put a hole between King's eyes; the FBI did not respond. Roy Wilkins was threatened with assassination if he did not leave the country. A cartoon in the August 27th Roanoke World News depicted marchers with placards headed toward a big barrel labeled "Washington, D.C." with the title "Powder Keg" above it.

The Washington, D.C. police forces were mobilized to full capacity for the march, including reserve officers and deputized firefighters. A total of 5,900 police officers were on duty. The government mustered 2,000 men from the National Guard, and brought in 3,000 outside soldiers to join the 1,000 already stationed in the area.

The FBI and Justice Department refused to provide preventative guards for buses traveling through the South to reach D.C.

The Washington, D.C. police forces were mobilized to full capacity for the march, including reserve officers and deputized firefighters. A total of 5,900 police officers were on duty. The government mustered 2,000 men from the National Guard, and brought in 3,000 outside soldiers to join the 1,000 already stationed in the area.

The FBI and Justice Department refused to provide preventative guards for buses traveling through the South to reach D.C.

|

| Sign on Liquor Store Door |

Rustin pushed hard for an expensive ($16,000) sound system, maintaining "We cannot maintain order where people cannot hear." The system was obtained and set up at the Lincoln Memorial, but sabotaged on the day before the March. Its operators were unable to repair it. Walter Fauntroy contacted Attorney General Robert Kennedy and his civil rights liasion Burke Marshall, demanding that the government fix the system. Fauntroy reportedly told them: "We have a couple hundred thousand people coming. Do you want a fight here tomorrow after all we've done?" The system was successfully rebuilt overnight by the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

Traveling by road, rail, and air, thousands arrived in Washington D.C. Organizers persuaded New York's MTA to run extra subway trains after midnight on August 28, and the New York City bus terminal was busy throughout the night with peak crowds. A total of 450 buses left New York City from Harlem. Maryland police reported that "by 8:00 a.m., 100 buses an hour were streaming through the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel." One reporter, Fred Powledge, accompanied African-Americans who boarded six buses in Birmingham, Alabama for the 750-mile trip to Washington. The New York Times carried his report:

The 260 demonstrators, of all ages, carried picnic baskets, water jugs, Bibles and a major weapon - their willingness to march, sing and pray in protest against discrimination. They gathered early this morning [August 27] in Birmingham's Kelly Ingram Park, where state troopers once [four months previous in May] used fire hoses and dog to put down their demonstrations. It was peaceful in the Birmingham park as the marchers waited for the buses. The police, now part of a moderate city power structure, directed traffic around the square and did not interfere with the gathering... An old man commented on the 20-hour ride, which was bound to be less than comfortable: "You forget we Negroes have been riding buses all our lives. We don't have the money to fly in airplanes."John Marshall Kilimanjaro, a demonstrator traveling from Greensboro, North Carolina, said:

Contrary to the mythology, the early moments of the March—getting there—was no picnic. People were afraid. We didn't know what we would meet. There was no precedent. Sitting across from me was a black preacher with a white collar. He was an AME preacher. We talked. Every now and then, people on the bus sang 'Oh Freedom' and 'We Shall Overcome,' but for the most part there wasn't a whole bunch of singing. We were secretly praying that nothing violent happened.The march commanded national attention by preempting regularly scheduled television programs. As the first event of such magnitude ever initiated and dominated by African Americans, the march also was the first to have its nature wholly misperceived in advance. Dominant expectations ran from paternal apprehension to dread. On the television show Meet the Press, reporters grilled Roy Wilkins and Martin Luther King about widespread foreboding that "it would be impossible to bring more than 100,000 militant Negroes into Washington without incidents and possibly rioting." Life magazine declared that the capital was suffering "its worst case of invasion jitters since the First Battle of Bull Run." The Pentagon readied nineteen thousand troops in the suburbs and the jails shifted inmates to other prisons to make room for those arrested in mass arrests. Hospitals made room for riot casualties by postponing elective surgery. With nearly 1,700 extra correspondents supplementing the Washington press corps, the march drew a media assembly larger than the Kennedy inauguration two years earlier.

On August 28, more than 2,000 buses, 21 chartered trains, 10 chartered airliners, and uncounted cars converged on Washington. All regularly scheduled planes, trains, and buses were also filled to capacity.

Although Randolph and Rustin had originally planned to fill the streets of Washington, D.C., the final route of the March covered only half of the National Mall. The march began at the Washington Monument and was scheduled to progress to the Lincoln Memorial with a program of music and speakers. Demonstrators were met at the monument by speakers and musicians.

|

| Joan Baez and Bob Dylan |

The march failed to start on time because its leaders were meeting with members of Congress. To the leaders' surprise, the assembled group began to march without them. The leaders met the March at Constitution Avenue, where they linked arms at the head of a crowd in order to be photographed 'leading the march'.

|

| Leading the March on Constitution Avenue |

The formal rally began at 1:15 p.m. with the singing of the National Anthem. Representatives from each of the sponsoring organizations addressed the crowd from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial. Speakers (dubbed "The Big Ten") included The Big Six; three religious leaders (Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish); and labor leader Walter Reuther. None of the official speeches were by women.

Following an invocation by Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle, the opening remarks were given by march director Philip Randolph. “We are the advanced guard of a massive moral revolution for jobs and freedom,” Randolph declared to the rally. Randolph insisted “that real freedom will require many changes in the nation’s political and social philosophies and institutions.” For example, he explained, ending housing discrimination would require civil rights activists to assert that “the sanctity of private property takes second place to the sanctity of a human personality.” Lending a decidedly American flavor to that implicitly socialist ideal, Randolph asserted that the history of slavery placed African Americans at the forefront of the revolution. “It falls to the Negro to reassert this proper priority of values,” the seventy-four-year-old trade unionist declared, “because our ancestors were transformed from human personalities into private property.”

Following an invocation by Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle, the opening remarks were given by march director Philip Randolph. “We are the advanced guard of a massive moral revolution for jobs and freedom,” Randolph declared to the rally. Randolph insisted “that real freedom will require many changes in the nation’s political and social philosophies and institutions.” For example, he explained, ending housing discrimination would require civil rights activists to assert that “the sanctity of private property takes second place to the sanctity of a human personality.” Lending a decidedly American flavor to that implicitly socialist ideal, Randolph asserted that the history of slavery placed African Americans at the forefront of the revolution. “It falls to the Negro to reassert this proper priority of values,” the seventy-four-year-old trade unionist declared, “because our ancestors were transformed from human personalities into private property.”

|

| A. Philip Randolph at the podium |

John Lewis of SNCC was the youngest speaker at the event. His speech took the Kennedy Administration to task for how little it had done to protect southern blacks and civil rights workers under attack in the Deep South. Copies of the SNCC speech had been distributed on August 27, and met with immediate disapproval from many of the organizers. Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle objected most strenuously to a part of the speech that called for immediate action and disavowed "patience". The government (and more moderate civil rights leaders) could not countenance SNCC's explicit opposition of Kennedy's civil rights bill. That night, O'Boyle and other members of the Catholic delegation began preparing a statement announcing their withdrawal from the March. Reuther convinced them to wait and called Rustin; Rustin informed Lewis at 2 A.M. on August 28 that his speech was unacceptable to key members of the March. Lewis did not want to change the speech. Other members of SNCC, including Stokely Carmichael, were also adamant that the speech not be censored.

|

| John Lewis |

Even after toning down his speech, Lewis called for activists to "get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes".

The following speakers were labor leader Walter Reuther and CORE chairman Floyd McKissick (substituting for CORE director James Farmer, who had been arrested in a protest in Louisiana.).

The Eva Jessye Choir then sang, and Rabbi Uri Miller, president of the Synagogue Council of America, offered a prayer. He was followed by National Urban League director Whitney Young, the National Catholic Council for Interracial Justice (NCCIJ) director Methew Ahmann, and NAACP leader Roy Wilkins.

|

| Martin Luther King, Jr. |

King drew shouts from the crowd as he emphasized "the fierce urgency of now" in contrast to "the luxury of cooling off" and "the tranquilizing drug of gradualism." He said:

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy; now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice; now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood; now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children. It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and quality.He urged people to "conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline" and "not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence" or "a distrust of all white people." He answered those in Congress and newspaper opinion columns who wanted to know when the Negro would be satisfied:

We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.

We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one.

We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs reading "for whites only." We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, now we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

|

| Martin Luther King, Jr. |

And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal ... I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!

The speech has been memorialized by the National Park Service with an inscription on the spot where King stood to deliver the speech.

The second one was withholding of federal funds from all programs in which discrimination exists.

The third was desegregation of all school districts in 1963.

The fourth was enforcement of the 14th Amendment, reducing congressional representation of states where citizens are disenfranchised.

The fifth was a new executive order banning discrimination in all housing supported by federal funds.

The sixth was authority for the attorney general to institute injunctive suits when any constitutional right is violated.

The seventh was a massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers, Negro and white, on meaningful and dignified jobs at decent wages.

The eighth was a national minimum wage act that will give all Americans a decent standard of living. Government surveys show that anything less than $2 an hour fails to do this.

Number nine was a broad and fair labor standards act to include all areas of employment which are presently excluded.

The last, number 10, a federal fair employment practices act barring discrimination by federal, state and municipal governments and by employers, contractors, employment agencies and trade unions.

After reading each demand, Rustin asked the crowd, "What do you say?" and the crowd cheered in support.

Randolph led the crowd in a pledge to continue working for the march's goals.

Two government agents stood by in a position to cut power to the microphone if necessary.

The program was closed with a benediction by Morehouse College president Benjamin Mays. After a mass singing of "We Shall Overcome," the crowd dispersed. The march ended at 4:20 p.m.

Television networks interviewed participants in the march, carried the speeches, offered news commentary on the events, and queried Congressmen. A. C. Nielson recorded huge jumps in television viewing for the March on Washington. Europeans saw it as well, in coverage "that rivaled that given astronaut landings." The BBC devoted major evening programming to the march and broadcast live coverage as received from the Telestar satellite. Southern senators and representatives gave terse comments that the march would have no effect at all on voting in Congress and would not influence the Civil Rights Bill's passage. Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina believed that the telecast to Europe was misleading to people there because they would be led to conclude that African Americans have no freedom. Alabama Governor George Wallace condemned the March on Washington as communist-directed and disturbing the peace. Wallace cultivated an appearance of sympathy for southern African Americans and a paternalistic expression of concern that "our fine Negroes" are being "misled."

Many participants said they felt the March was a historic and life-changing experience. Nan Grogan Orrock, the a student at Mary Washington College, said:

"You couldn't help but get swept up in the feeling of the March. It was an incredible experience of this mass of humanity with one mind moving down the street. It was like being part of a glacier. You could feel the sense of collective will and effort in the air."

Fifteen-year-old Ericka Jenkins from Washington said:

I saw people laughing and listening and standing very close to one another, almost in an embrace. Children of every size, pregnant women, elderly people who seemed tired but happy to be there, clothing that made me know that they struggled to make it day to day, made me know they worked in farms or offices or even nearby for the government. I didn't see teenagers alone; I saw groups of teenagers with teachers. White people [were] standing in wonder. Their eyes were open, they were listening. Openness and nothing on guard—I saw that in everybody. I was so happy to see that in the white people that they could listen and take in and respect and believe in the words of a black person. I had never seen anything like that.Days later Rustin emphasized that the march was “not a climax but a new beginning.” In October 1963, Rustin published "The Meaning of the March on Washington" in Liberation:

The ghastly bombings in Birmingham point up the success of the March on Washington — and at the same time expose the inadequacy of those of us who organized it. We were bombed because we were winning, not because we were losing. But our biggest mistake was to have carried out such a powerful March, with a quarter of a million people in the streets, and not to have understood that the counter-revolutionaries would strike back in some such demented way. We can perhaps be excused a little, in that we were overwhelmed with the machinery and busy working out our next moves. But we should have had the next steps ready. We should have done our part to get the masses ready to move.

. . . Historically, the March on Washington broadened the base of the civil rights movement. The March was not a Negro action; it was an action by Negroes and whites together. Not just the leaders of the Negro organizations, but leading Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish spokesmen called the people into the streets. And Catholics, Protestants, and Jews, white and black, responded. This response obviated the danger that the revolt would be an argument between Negroes and whites over a few jobs. It began the process of focusing attention where it belongs: on the problem of what kind of economic and political changes are required to make it possible for everyone to have jobs.

The civil rights movement alone cannot provide jobs for all. It cannot solve the problems raised by automation — and automation deprives more Negroes of jobs than any other single factor, including prejudice. Nor can it tackle alone the coalition of Dixiecrats and plutocrats which impairs the political and economic health of the country. . .

Most Americans are more interested in order than in law, more interested in law than in justice. This means that in the normal course of events they will line up behind the status quo rather than make the basic changes required to meet human needs. In practical terms, this means that it is better for the Negro to go on suffering for another hundred years than to cause a disturbance in Washington or embarrass Congress. That is why it was important to get thousands of white people into the streets in Washington. . . . until the successful completion of the March, the method was on trial. "Would 'they' not bring their guns and razors to Washington?" The March came off so beautifully that not only did it reassure our white allies, it also put our opponents on the spot. That some of them responded so cruelly, with the bombings in Birmingham (incited as they were, whether intentionally or not, by Governor Wallace and the "hold-the-line" Senators) and the subsequent shootings by Southern policemen, heightened the contrast between the nonviolent revolutionists and the status quo defenders of "law and order.

. . . Inseparable from the problem of politics-as-usual is the problem of "business as usual." Historically, the significance of the March will be seen to have less to do with civil rights than with economic rights: the demand for jobs. The problem of how to get jobs for Negroes is really the problem of how to get jobs for people. And this brings us up against the whole power structure. The tentacles of the power structure reach all the way from Birmingham to New York and Pittsburgh and Chicago, even as they also reach from New York, Pittsburgh, and Chicago to Birmingham, Danville, and Jackson. We must put the total structure of the country under scrutiny, including the war economy. Not only does war industry fail to provide butter and schools, houses and hospitals, but it provides the least jobs per dollar spent of any sector of industry. It is the most highly automated part of the economy.

Under automation, we are faced with a new civil war situation all over again. Once again the union cannot endure only half free. It cannot survive if it is divided into those who receive high incomes and those who are unemployed and subsist on the dole. The white unemployed and the labor unions have not challenged this situation. The March did. The program was inadequate, but a crucial first step was made. . .

The need of the civil rights movement is not to get someone else to manipulate power. They will not do it in our interests. Our need is to exert our own power, and the main power we have is the power of our black bodies, backed by the bodies of as many white people as will stand with us. We need to use these bodies to create a situation in which society cannot function without yielding to our just demands. We need to make things unworkable until Negroes have jobs, equality, and freedom.

There has been talk of violence, especially by those in the North. If violence could ever be justified, it would be justifiable now for the Negroes of Birmingham.

But we are not interested in retaliation. We want our freedom. And we cannot get our freedom with guns. You cannot integrate a school or get a job with a machine gun.

The only way we can do these things is to use our bodies in such a way that the school or the factory cannot operate successfully without integrating us.

The same holds true for our pressing overall demands. The civil rights movement cannot go much further without taking on society. Until we do so there will be a continuation of the brutalization and serfdom that is the daily lot of the majority of Negroes and a large number of whites. We need to go into the streets all over the country and to make a mountain of creative social confusion until the power structure is altered.

We need in every community a group of loving troublemakers, who will disrupt the ability of the government to operate until it finally turns its back on the Dixiecrats and embraces progress.

My words may seem extreme. But both the demands and the needs of the Negro people go so far beyond the present political possibilities that disruption is inevitable. The only question is whether it will be violent or nonviolent, creative or uncreative. In the present framework of Southern brutality, aided by the leaders of both major parties and abetted by the apathy and "patience" of the white masses, there is no longer any viability for a minority nonviolent movement. Furthermore, there is a moral deterioration that takes place if the individual must face the brutalization and murder of little children, the furious violence of the Southern police, and the hypocrisy of the Kennedy administration, without a big enough response.

It is not a question of debating, in a vacuum, the morality of violence and nonviolence, on the one hand, or of "respect for law" versus civil disobedience, on the other. It is a question of program, of taking the offensive in an adequate way. For this, there must the masses in motion.

There is no possibility of a practical program through violence.

But unless those who organized and led the March on Washington hold together and give the people a program based on mass action, the whole situation will deteriorate and we will have violence, tragic self-defeating violence which will do immeasurable harm to whites and Negroes alike and will postpone indefinitely the day when all men will be free.

The mass media identified King's speech as a highlight of the event and focused on this oration to the exclusion of other aspects. For several decades, King took center stage in narratives about the March. More recently, historians and commentators have acknowledged the role played by Bayard Rustin in organizing the event.

For hundreds of civil rights veterans, August 28 will also always be Bayard’s Day, the crowning achievement of one of the movement’s most effective, and unconventional, activists.

“When the anniversary comes around, frankly I think of Bayard as much as I think of King,” says Eleanor Holmes Norton, a March volunteer. “King could hardly have given the speech if the march had not been so well attended and so well organized. If there had been any kind of disturbance, that would have been the story.”

"Bayard Rustin, in my judgment, the only man in the United States who could have organized that march."

In the weeks before the march, planners were checking off details by the thousand: buses booked, speeches vetted, slogans written, portable toilets rented. At the Harlem headquarters, Rustin toggled between the political (brokering podium time for dozens of competing groups) and the practical (determining whether peanut butter or sandwiches with mayonnaise would stand up better in a Washington August). Between phone calls, he drilled the hundreds of off-duty police officers and firefighters who had volunteered to serve as marshals. He made them take off their guns and coached them in the techniques of nonviolent crowd control he had brought back from a pilgrimage to India.

“We used to go out to the courtyard to watch,” says Rachelle Horowitz, a longtime Rustin lieutenant who served as the march’s transportation coordinator. “It was like, see Bayard tame the police.”

For hundreds of civil rights veterans, August 28 will also always be Bayard’s Day, the crowning achievement of one of the movement’s most effective, and unconventional, activists.

“When the anniversary comes around, frankly I think of Bayard as much as I think of King,” says Eleanor Holmes Norton, a March volunteer. “King could hardly have given the speech if the march had not been so well attended and so well organized. If there had been any kind of disturbance, that would have been the story.”

|

| Eleanor Holmes Norton |

In the weeks before the march, planners were checking off details by the thousand: buses booked, speeches vetted, slogans written, portable toilets rented. At the Harlem headquarters, Rustin toggled between the political (brokering podium time for dozens of competing groups) and the practical (determining whether peanut butter or sandwiches with mayonnaise would stand up better in a Washington August). Between phone calls, he drilled the hundreds of off-duty police officers and firefighters who had volunteered to serve as marshals. He made them take off their guns and coached them in the techniques of nonviolent crowd control he had brought back from a pilgrimage to India.

“We used to go out to the courtyard to watch,” says Rachelle Horowitz, a longtime Rustin lieutenant who served as the march’s transportation coordinator. “It was like, see Bayard tame the police.”

The 53-year-old known at the time as “Mr. March-on-Washington” was a lanky, poetry-quoting black Quaker intellectual who wore his hair in a graying pompadour. He’d had a fleeting association with a communist youth group in the 1930s and had been a Harlem nightclub singer in the 1940s (and was still given to filling corridors and meeting rooms with his high troubadour tenor). He had gone to prison as a conscientious objector during World War II — he used his time there to take up the lute — and had been jailed more than 25 other times as a protester.

In films of the rally, Rustin is a constant presence on the podium, blowing cigarette smoke behind Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, mouthing the words to “Stand by Me” with Mahalia Jackson. He is at King’s side, mesmerized, or maybe exhausted, as King thunders across the ages, “Free at last, free at last, thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

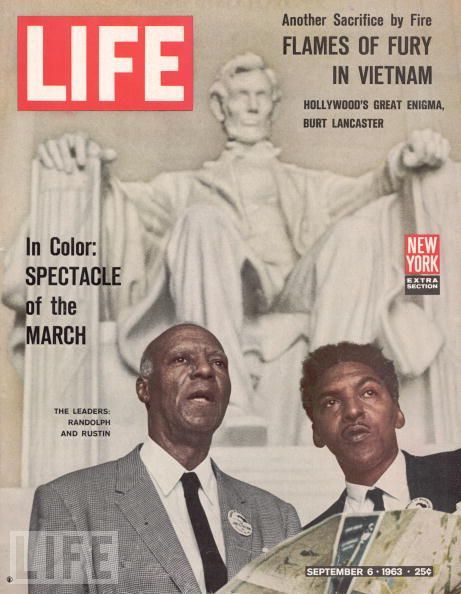

A week later, Rustin’s picture was on the cover of Life magazine, standing next to Randolph at the feet of the towering marble Lincoln.

A week later, Rustin’s picture was on the cover of Life magazine, standing next to Randolph at the feet of the towering marble Lincoln.

|

| LIFE Magazine Cover with A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin |

Joyce Ladner, a SNCC representative, remembered:

"Lena Horne came over where we were standing to talk to my mother, and in listening to them [it] was my first experience in learning some of the things that my mother had been subjected to," Lee-Payne recalls. "Having to enter hotels through the back door, in things that they saw, in driving in a bus or on a train going from one state or city to the other. Those were things that my mother had never shared with me." Horne and Lee-Payne's mother didn't talk for a very long time, Lee-Payne says, "but they talked about the purpose for being there and what it meant to them, so in sharing those things, it was enlightening to me."

SNCC organizer Bob Zellner wrote in 2002 that

In 2010, Glenn Beck held a rally at the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, the anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington. Martin Luther King III, a son of Dr. King, wrote the following in an editorial in the August 25 edition of The Washington Post:

Joyce Ladner

We went to Washington the day before the March and we checked into the old Statler Hilton hotel on 16th Street. Malcolm X held forth in the Hilton hotel lobby all afternoon. I was absolutely mesmerized by him. So were a lot of others because there was a crowd of people around him all the time. I remember that he called the March on Washington the "Farce on Washington." It gave me a lot to think about. Were we engaged in a farce? Had I spent the summer working on a cause that was nothing more than a show? I decided not.

Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte and Charlton Heston at the Lincoln Memorial

My yellow "Reserved Section" pass allowed me to see the March from the vantage point of the Lincoln Memorial. Bayard was very democratic about who could be on the podium. There were union workers, civil rights leaders including Roy Wilkins, John Lewis, Whitney Young, and there were the celebrities of the day — Josephine Baker, who had flown in from Paris, the civil rights fundraisers Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte, Jimmy Baldwin, Joan Baez, Bobby Dylan, Odetta, Charlton Heston, Lena Horne, Marlon Brando and Mahalia Jackson for starters...

|

| Charlton Heston with James Baldwin and Marlon Brando |

What I remember most is standing on the podium looking out at the 250, 000 people. It was a sight to behold. One had to see it to believe it. Despite the conflict over John's speech, I felt emboldened because of the large number of people who came. I didn't feel so isolated anymore. I was also very happy that our hard work that summer had led to such a great success.

I also remember when Lena Horne took me by the hand and told Nancy Dickerson, the CBS correspondent to interview me instead of her. She said "this young lady lives in Mississippi." This was the first time I understood the power of the media because Mother saw the interview on CBS news. I reasoned that if Mother could see the support for the March from our little hamlet of Palmers Crossing, (outside Hattiesburg) Mississippi, then surely she would feel that the commitment Dorie and I made to fight for justice was worth the price. I lived to see the day when she was more proud than frightened for us.

Edith Lee-Payne was from Detroit, and the day of the March was her 12th birthday. She still has the black and white banner she's holding in the picture. In the top left corner it says, "I was there." Her Aunt Edith was volunteering at the Red Cross tent. Lee-Payne's mother had once worked as an entertainer and knew a lot of people in show business. She was a dancer who opened for Cab Calloway, and she sometimes baby-sat for Sammy Davis Jr. when he was just a child star.

"Lena Horne came over where we were standing to talk to my mother, and in listening to them [it] was my first experience in learning some of the things that my mother had been subjected to," Lee-Payne recalls. "Having to enter hotels through the back door, in things that they saw, in driving in a bus or on a train going from one state or city to the other. Those were things that my mother had never shared with me." Horne and Lee-Payne's mother didn't talk for a very long time, Lee-Payne says, "but they talked about the purpose for being there and what it meant to them, so in sharing those things, it was enlightening to me."

SNCC organizer Bob Zellner wrote in 2002 that

The impact the march had on me was that it provided dramatic proof that the sometimes quiet and always dangerous work we did in the deep South had had a profound national impact. The spectacle of a quarter of a million supporters and activist gave me an assurance that the work I was in the process of dedicating my life to was worth doing.

It is hard to enumerate the changes the last forty years have witnessed. Formal and de jure segregation is dead for the moment. White supremacy and racism has learned to be more effective and less visible. White privilege can be maintained without the overt trappings of apartheid. Class can replace race as the great divide and "respectable" people are free to advocate and enable massive upward distribution of wealth without being seen as sexist, racist, or any of those other to be avoided labels.

The forces that constituted the target of the March those forty years ago are still in power and MLK is now an emasculated saint of sweetness and light and "nonviolence." Those who have elevated him and now sing his praises, did not sing his praises when he was preparing a radical poor people march on Washington, and opposing the war in Vietnam. And it goes without saying that our non-elected President and his family retainers have not adopted nonviolence as their weapon of choice in Afghanistan and the new world order of continuous war where the terrorists replace the worn out old red bear.In 2013, the Economic Policy Institute launched a series of reports around the theme of "The Unfinished March". These reports analyze the goals of the original march and assess how much progress has been made. They echo the message of Randolph and Rustin that civil rights cannot transform people's quality of life unless accompanied by economic justice. They say that many of the March's primary goals—including housing, integrated education, and widespread employment at living wages—have not been accomplished. They argue that although legal advances were made, black people still live in concentrated areas of poverty ("ghettos"), where they receive inferior education and suffer from widespread unemployment.

In 2010, Glenn Beck held a rally at the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, the anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington. Martin Luther King III, a son of Dr. King, wrote the following in an editorial in the August 25 edition of The Washington Post:

This weekend Glenn Beck is to host a "Restoring Honor" rally at the Lincoln Memorial. While it is commendable that this rally will honor the brave men and women of our armed forces, who serve our country with phenomenal dedication, it is clear from the timing and location that the rally's organizers present this event as also honoring the ideals and contributions of Martin Luther King Jr.

I would like to be clear about what those ideals are.

Vast numbers of Americans know of my father's leadership in opposing segregation. Yet too many believe that his dream was limited to achieving racial equality. Certainly he sought that objective, but his vision was about more than expanding rights for a single race. He hoped that even in the direst circumstances, we could overcome our differences and replace bitter conflicts with greater understanding, reconciliation and cooperation.

My father championed free speech. He would be the first to say that those participating in Beck's rally have the right to express their views. But his dream rejected hateful rhetoric and all forms of bigotry or discrimination, whether directed at race, faith, nationality, sexual orientation or political beliefs. He envisioned a world where all people would recognize one another as sisters and brothers in the human family. Throughout his life he advocated compassion for the poor, nonviolence, respect for the dignity of all people and peace for humanity.

Although he was a profoundly religious man, my father did not claim to have an exclusionary "plan" that laid out God's word for only one group or ideology. He marched side by side with members of every religious faith. Like Abraham Lincoln, my father did not claim that God was on his side; he prayed humbly that he was on God's side.

He did, however, wholeheartedly embrace the "social gospel." His spiritual and intellectual mentors included the great theologians of the social gospel Walter Rauschenbush and Howard Thurman. He said that any religion that is not concerned about the poor and disadvantaged, "the slums that damn them, the economic conditions that strangle them and the social conditions that cripple them[,] is a spiritually moribund religion awaiting burial." In his "Dream" speech, my father paraphrased the prophet Amos, saying, "We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream."

The title of the 1963 demonstration, "The Great March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom," reflected his belief that the right to sit at a lunch counter would be hollow if African Americans could not afford the meal. The need for jobs and shared economic prosperity remains as urgent and compelling as it was 47 years ago. My father's vision would include putting millions of unemployed Americans to work, rebuilding our tattered infrastructure and reforms to reduce pollution and better care for the environment.

In my efforts to help realize my father's dream, supporting justice, freedom and human rights for all people, I have conducted nonviolence workshops and outreach in communities across this country and numerous other nations. My experiences affirm the enduring truth of my father's words: that "injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere" and that "we are all bound together in a single garment of destiny."

I pray that all Americans will embrace the challenge of social justice and the unifying spirit that my father shared with his compatriots. With this commitment, we can begin to find new ways to reach out to one another, to heal our divisions, and build bridges of hope and opportunity benefiting all people. In so doing, we will not merely be seeking the dream; we will at long last be living it.

No comments:

Post a Comment