Lewis "Lew" Wallace was born in Brookville, Franklin County, Indiana to David Wallace and Esther French (Test) Wallace. His father was a graduate of the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York.

|

| Franklin County, Indiana |

|

| David Wallace |

His father married 19-year-old Zerelda Gray Sanders, who became a prominent suffragist and temperance advocate. They had six children together, and she was stepmother to David Wallace's three sons from his first marriage. Lew rejoined his family in Indianapolis.

In 1842, when Wallace learned of Texas’ War of Independence, he and a friend provisioned a canoe and set out down the White River to offer their services to James Bowie and Davy Crockett. Lew’s grandfather apprehended them a few miles downriver. A year later, when he was sixteen, his father kicked him out of the house and sent him off to earn a living, hoping to steer him away from art and other delinquent tendencies.

With reluctance, Lew followed his father into the legal profession, and he was preparing for the bar exam when the United States declared war with Mexico in 1846. He raised a company of militia and was elected a second lieutenant in the 1st Indiana Infantry regiment. He rose to the position of regimental adjutant and the rank of 1st lieutenant, serving in the army of Zacahary Taylor.

Lew imagined the conquest of Mexico would be full of the “gallantries” he’d read about in novels. Instead, his regiment was ordered to garrison a camp at the mouth of the Rio Grande, across the river from a small Mexican smuggler’s outpost, which the soldiers called “Bagdad.” The camp was soon beset with an epidemic of diarrhea so fatal that the survivors ran out of wood for coffins. The men heard of General Taylor’s victories from passing steamboats.

After hostilities, he was mustered out of the volunteer service on June 15, 1847, at the age of 20.

He was 33 years old when the Civil War began.

|

| Lew Wallace, circa 1850s |

As a young lawyer, he strove to win the favor of his future wife, Susan Arnold Elston, sister-in-law of U.S. Senator Henry S. Lane of Crawfordsville, the “Athens of Indiana.” The town acquired the nickname because of its prominent citizens, such as Lane, who helped found the Republican party, and the intellectual community of Wabash College, founded in 1832.

On May 6, 1852 in Crawfordsville, Wallace married Susan. They had one son, Henry Lane Wallace (1853–1926).

|

| Susan Elston Wallace |

In 1856, he was elected to the Indiana State Senate.

One day, Wallace accompanied a colleague to a tavern in nearby Danville, Illinois. The young lawyers met a man Wallace described as “the gauntest, quaintest, and most positively ugly man who had ever attracted me enough to call for study.” The man was engaged in a storytelling contest with several local lawyers, and, was running away with the competition, exhausting all comers with a seemingly endless store of well-spun yarns. It was Wallace’s first glimpse of Abraham Lincoln. His admiration for the fellow lawyer contributed to Wallace's decision to join the Republican Party.

His father, David Wallace died suddenly, without having been ill, on September 4, 1859 in Indianapolis, Indiana.

One day, Wallace accompanied a colleague to a tavern in nearby Danville, Illinois. The young lawyers met a man Wallace described as “the gauntest, quaintest, and most positively ugly man who had ever attracted me enough to call for study.” The man was engaged in a storytelling contest with several local lawyers, and, was running away with the competition, exhausting all comers with a seemingly endless store of well-spun yarns. It was Wallace’s first glimpse of Abraham Lincoln. His admiration for the fellow lawyer contributed to Wallace's decision to join the Republican Party.

|

| Abraham Lincoln |

|

| David Wallace |

Although not a strong abolitionist at the start of the Civil War, Indiana's Republican governor Oliver P. Morton asked him to help raise troops. Wallace, who sought a second chance for military glory, agreed on the condition that he be given command of a regiment.

|

| Oliver P. Morton |

|

| Winslow Homer's Illustration of Wallace in 1861 |

|

| Harper Weekly's Illustrations |

In February 1862, while preparing for an advance against Fort Henry, General Ulysses S. Grant sent two wooden gunboats down the Tennessee River for one last reconnaissance of the fort with Wallace aboard. During the campaign, Wallace's brigade was attached to General Charles Smith's division and occupied Fort Heiman across the river from Fort Henry. Grant's superior, General Henry Halleck, was concerned about Confederate reinforcements retaking the forts, so Grant left Wallace with his brigade in command at Fort Henry while the rest of the army moved overland toward Fort Donelson.

|

| Ulysses S. Grant |

|

| Lew Wallace, 1862 |

There were two main routes by which Wallace could move his unit to the front, and Grant (according to Wallace) did not specify which one he should take. Wallace chose to take the "upper" shunpike, which he believed was more usable and led to Shiloh Church; he had the day before written a letter to another officer stating his intention to do so. Grant later claimed that he had specified that Wallace take the "lower" route along the river to Pittsburg Landing.

Wallace arrived only to find that Sherman had been forced back and was no longer where he expected to find him. Sherman had been pushed back so far that Wallace was to the rear of the advancing Southern troops. A messenger from Grant arrived at 11:30 a.m. with word that Grant was wondering where Wallace was, and why he had not arrived near Pittsburg Landing, where the Union was making its stand.

Wallace believed he could launch a viable attack from where he was and hit the Confederates in the rear, but decided to countermarch his troops back along the same route and via a circuitous path direct to the bridge crossing Snake and Owl creeks. Rather than realigning his troops so that the rear guard would be in the front, Wallace chose to countermarch his column; he argued that his artillery would have been greatly out of position to support the infantry when it would arrive on the field. Wallace marched back to the midpoint on the "upper" road. He proceeded to march over a new third path that would intersect with the lower road to join the army on the field, but the road had been left in terrible conditions by recent rainstorms and previous Union marches. Progress was extremely slow, marching and countermarching a total of 15 miles in six and a half hours.

|

| Generals at the Battle of Shiloh |

“Well, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?” Sherman is said to have remarked to Grant on the night of April 6. “Yes,” Grant replied. “Lick ’em tomorrow, though.” With Wallace’s division finally in place, and Buell’s reinforcements having arrived overnight, Grant unleashed a vicious counterattack on April 7, pushing the rebels back over ground still littered with the dead and dying from the previous day’s fight. Wallace's division held the extreme right of the Union line and was the first to attack on April 7. Realizing they were now outnumbered, the Confederates beat a retreat in the afternoon.

At first, there was little fallout from this. Wallace was the youngest general of his rank in the army and was something of a "golden boy." Soon, however, civilians in the North began to hear the news of the horrible casualties at Shiloh, and the Army needed explanations. Both Grant and his superior, Halleck, placed the blame squarely on Wallace, saying that his incompetence in moving up the reserves had nearly cost them the battle. Sherman, for his part, remained silent on the issue.

|

| Generals Sherman and Grant |

In August 1862, Confederate General Kirby Smith and his forces moved through Kentucky; the Battle of Richmond was fought, and the results were disastrous for the Federals: 4,000 prisoners captured dwarfed approximately 1,000 killed and wounded Federal soldiers - all at a cost of about 450 killed and wounded Confederates. Ten thousand stands of arms, nine guns, and the Federal supply train were captured. Federal strength in the Bluegrass Region of Kentucky was effectively wiped out. Lexington, and the capital of Frankfort, lay scant miles ahead. The important cities of Cincinnati and Louisville appeared wide open to Confederate attack.

|

| Cincinnati Militia |

|

| View from Hooper Battery, Defense of Cincinnati |

On September 2, Kirby Smith took Lexington, and on the 3rd, Confederate cavalry took Frankfort. General Heth, with four brigades, fanned north to cover the approaches to Cincinnati. Confederate infantry was moving to take Falmouth and Williamstown, the two major approaches to Cincinnati. Farmers were hurrying livestock north towards the Ohio River.

In its lead editorial, The Cincinnati Gazette declared: "TO ARMS! TO ARMS! The time for playing war has passed. The enemy is fast approaching our city. Kentucky has already been invaded and our cities for the first time since the rebellion are seriously threatened . . . Let us prepare to resist an army of 100,000 men bent on our destruction."

General Ormsby Mitchel (a former professor of astronomy at the University of Cincinnati) soon joined generals Wallace and Wright, and Colonel Charles Wittlesey of the Engineering Corps: they set out to install a series of forts, gun emplacements, and rifle pits in the hills of Northern Kentucky.

General Ormsby Mitchel (a former professor of astronomy at the University of Cincinnati) soon joined generals Wallace and Wright, and Colonel Charles Wittlesey of the Engineering Corps: they set out to install a series of forts, gun emplacements, and rifle pits in the hills of Northern Kentucky.

|

| Ormsby Mitchel |

Wallace learned about the poor treatment of the men. On September 4, 1862, he commissioned Judge William Martin Dickson as commander of the Black Brigade. After receiving his appointment, Colonel Dickson changed the brigade into a working regiment. On the evening of September 4, 1862, Dickson dismissed the men to tend to their families as well as gather personal supplies for the days of work ahead. He promised them that he was forming the brigade for fatigue duty and they "should be kept together as a distinct body,... that they should receive protection and the same treatment as white men,... and that their sense of duty and honor would cause them to obey all orders given, and thus prevent the necessity of any compulsion..." In return for these promises, Dickson expected the men to meet the next morning for work on the defensive fortifications. In his official report to Ohio Governor John Brough Dickson stated that around 400 men were present when he dismissed the brigade on September 4, 1862. The next day over 700 men reported ready for duty.

|

| Memorial to Black Brigade, Cincinnati, Ohio |

|

| Memorial to Black Brigade, Cincinnati, Ohio |

Kirby Smith had General Henry Heth push forward from Georgetown towards Cincinnati on September 6 with 6,000 troops. One of the hoped-for aspects of Braxton Bragg's invasion of Kentucky was that the predominantly Pro-Southern Bluegrass Region would come forth and help fill thinning Confederate ranks. For this purpose, Bragg brought some 20,000 additional rifles with which to equip these volunteers. Regretfully for Bragg, very few volunteers came forward.

|

| Henry Heth |

Public activities were restored, although, interestingly enough, circulars had to be issued in Cincinnati to the press regarding the printing of articles "of a seditious and treasonable character", and the city's journalists were requested "to exercise great caution in the publication of articles calculated unnecessarily to disturb the public mind."

Wallace received the nickname "Savior of Cincinnati" for his actions in September 1862. Before leaving, Wallace issued the following proclamation:

Several years after the war, Wallace met General Heth in the bar of the Burnet House and learned that Heth would have held Cincinnati for $15,000,000 ransom or else have sacked the city. The two veterans compared notes on the campaign, discussed the spies each had sent into the other's camp, and Heth learned that the seemingly unguarded spot where he had planned to attack was actually a trap set up by Wallace in which the Confederates would have been cut to pieces in a cross fire of artillery and sharpshooters.

The fact that a battle was not fought is due to Wallace's prompt and decisive action. Had he not taken command, nothing would have stood in the way of the Confederate army, which could have taken the city. Heth's plans to hold the city for ransom (as Jubal Early later did to Frederick, Maryland) or sack it indicated that he felt his forces were too weak to hold it for the Confederacy, but he might have caused the Union to divert troops from critical operations elsewhere. Wallace earned the city's gratitude, but the absence of a battle prevent him from regaining the standing he lost at Shiloh and kept the defense of Cincinnati from being as celebrated.

General Grant relieved Wallace of his command after learning of the defeat of Monocacy, but re-instated him two weeks later. Grant's memoirs of the war praised Wallace's delaying tactics at Monocacy:

During the disputed election of 1876, the Republican Party sent Wallace to oversee the original Florida recount. For his role in delivering the White House to Rutherford B. Hayes, he was rewarded with the governorship of the New Mexico territory, during a time of violence and political corruption.

Inspiration for Wallace’s next second novel came from an unlikely source: his own ignorance. Wallace often told the story of how, on a train trip in 1876, he met the well-known agnostic Colonel Robert Ingersoll, also a veteran of Shiloh.

The train was bound for Indianapolis and the Third National Soldiers Reunion, where thousands of Union Army veterans planned to rally, reminisce, and march in a parade. After hours of conversation in which Ingersoll questioned the evidence for God, heaven, Christ, and other theological concepts, Wallace came away realizing how little he knew about his own religion. “I was ashamed of myself, and made haste now to declare that the mortification of pride I then endured . . . ended in a resolution to study the whole matter, if only for the gratification there might be in having convictions of one kind or another.” Departing the train, he walked the pre-dawn streets of Indianapolis alone.

In true lawyer style, he hit the books: First the Bible, and then every reference book about the ancient Middle East he could find. He suspected that a novel about Jesus Christ would be scrutinized by experts, so the plants, birds, clothes, food, buildings, names, places—everything had to be exact. “I examined catalogues of books and maps, and sent for everything likely to be useful. I wrote with a chart always before my eyes—a German publication showing the towns and villages, all sacred places, the heights, the depressions, the passes, trails, and distances.” He traveled to multiple libraries across the country to ensure he had the exact measurements for the workings of a Roman trireme. He provided detail after detail on the design of Persian versus Greek versus Roman chariots. He did everything short of going to Jerusalem himself. Years later, when he actually visited the Holy Land, he tested his research and proudly said, “I find no reason for making a single change in the text of the book.”

Offering the satisfaction of a revenge plot while preaching the gospel of compassion, Ben-Hur resonated with a country that was moving from vengeance to forgiveness itself. The National Soldiers Reunion that Wallace and Ingersoll attended in 1876, at the tail end of Reconstruction, was a strictly Union event, with speeches and parades honoring the North’s just cause. But at the Reunion held just two years later in 1878, in Cincinnati, blue mingled with gray: Joe Johnston, John Bell Hood, and Robert E. Lee’s nephew Fitzhugh were among the invitees, and the order of the day was celebrating the heroism of combatants on both sides of the conflict. Ex-rebels were now in the halls of power as well.

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880) was not an immediate success, but within two years it had gained momentum. The same morning President Garfield finished reading it, he wrote a thank-you note to Wallace, and within the month offered him the ambassadorship to Turkey. Ulysses S. Grant confessed he was so absorbed with the story, he read it for thirty hours straight. The novel’s readership wasn’t confined to Union veterans. In an Indiana newspaper, the historian S. Chandler Lighty discovered Winnie Davis’ account of reading Ben-Hur aloud to her father “from 10 o’clock until daybreak, both of us oblivious to the flight of time.” Her father was Jefferson Davis, the former Confederate president.

Victorians who swore off novels because of their immoral influence eagerly picked up Ben-Hur—were even encouraged to by their pastors. It became required reading in grade schools across the United States. For those who considered theater sinful, the spectacle of the Broadway version lured them in for twenty-one years, not to mention the touring show that required four entire trains to transport all the scenery and livestock. More than twenty million people saw Ben-Hur on stage between 1899 and 1920, complete with live horses running on hidden treadmills to recreate the chariot race. One reverend from San Francisco, who had never attended a play, was finally tempted into seeing the much-hyped production. He described the experience as both “delightful and disappointing,” noting the clunky stagecraft and stilted acting. Yet he was won over enough to declare that he would return to the theater again.

The book made Lew Wallace a celebrity, sought out for speaking engagements, political endorsements, and newspaper interviews.

It was the vindication Wallace had longed for since 1862. But even this failed to satisfy him. The Century article, with its repetition of the standard account of Wallace’s mistakes, became the Shiloh chapter of Grant’s memoirs. The exoneration appeared as a footnote, one that Wallace worried would be ignored by most readers. Rightly, as it would turn out.

But Ben-Hur opened the doors of opportunity. The position of minister plenipotentiary to the Ottoman Empire had an annual salary of $7,500, a princely sum for the time. He served from 1881 to 1885; Wallace’s first official duty as minister to Turkey was to relieve his predecessor—former General James Longstreet, the trusted Lee lieutenant who had fought at Chickamauga, Antietam, and Gettysburg. After the war, Longstreet had joined the Republican Party and been embraced by his former enemies.

Despite using many friends in Washington to influence the government, Wallace's offer in 1898 to raise and lead a division of soldiers for the Spanish-American War was refused; when he attempted to enlist as a private, he was rejected given his age of 71.

There were so many rumors about Wallace’s faith—that he was an atheist or that he had gone to the Holy Land to disprove the existence of Christ—he felt it necessary to introduce his autobiography by dispelling them. He wrote in his autobiography, “In the very beginning, before distractions overtake me, I wish to say that I believe absolutely in the Christian conception of God. As far as it goes, this confession is broad and unqualified, and it ought and would be sufficient were it not that books of mine—Ben-Hur and The Prince of India—have led many persons to speculate concerning my creed. . . . I am not a member of any church or denomination, nor have I ever been. Not that churches are objectionable to me, but simply because my freedom is enjoyable, and I do not think myself good enough to be a communicant.”

His stepmother, Zenalda Wallace, died March 19, 1901 and was buried next to her husband in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

Wallace died of stomach cancer at the age of 77 on February 15, 1905 in Crawfordsville.

In the days following his death, nearly every newspaper in the country carried an obituary, many of them as lead stories that jumped to full-page spreads. The Cincinnati Enquirer announced the news with a headline overwrought even by fin de siècle standards, though not atypical of the coverage:

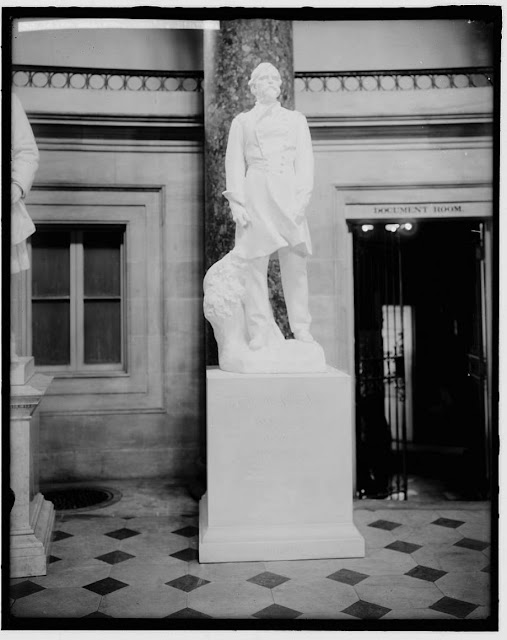

The state of Indiana commissioned a marble statue of Wallace dressed in a military uniform, which was made by the sculptor Andrew O'Connor. It was placed in the National Statuary Hall Collection in 1910. He is the only novelist honored in the hall.

In Cincinnati, The Cincinnati Gazette summed up the situation on September 14:

"Thanks to the promptitude of Generals Wright and Wallace, and the patriotism, courage and valor of the people, the Rebel movement toward Cincinnati has been frustrated and rolled back. In a remarkably brief space of time our cities, which were practically defenseless, became bastions of military might as our whole male population arose enmasse. The patience that they endured, the severe labor of trenches and tented fields for many days in succession presented a remarkable instance of how quickly a citizen can be converted into a soldier. Assisted by loyalists from other areas, we had an army in less than a week that was a proud example of what the West can do to meet invasion. Cincinnati is a large and wealthy city, attractive as a prize to the enemy. Hereafter, it must not be undefended as hitherto; we must have troops for home defense."

|

| Monument to Dickson and Wallace, Cincinnati, Ohio |

For the present, at least, the enemy have fallen back and your cities are safe….When I assumed command there was nothing to defend you with, except a few half-finished works and some dismounted guns; yet I was confident. the energies of a great city are boundless; they have only to be aroused, united and directed. You were appealed to. The answer will never be forgotten.

Paris may have seen something like it in her revolutionary days, but the cities of America never did. Be proud that you have given them an example so splendid. The most commercial of people, you submitted to a total suspension of business, and without a murmur adopted my principle–'Citizens for labor, soldiers for battle.'

In coming time, strangers, viewing the works on the hills of Newport and Covington, will ask, 'Who built these intrenchments?' You will answer, 'We built them.' If they ask, 'Who guarded them?' you can reply, 'We helped in thousands.' If they inquire the result, your answer will be, 'The enemy came and looked at them, and stole away in the night.'

You have won much honor; keep your organizations ready to win more. Hereafter be always prepared to defend yourselves.

The fact that a battle was not fought is due to Wallace's prompt and decisive action. Had he not taken command, nothing would have stood in the way of the Confederate army, which could have taken the city. Heth's plans to hold the city for ransom (as Jubal Early later did to Frederick, Maryland) or sack it indicated that he felt his forces were too weak to hold it for the Confederacy, but he might have caused the Union to divert troops from critical operations elsewhere. Wallace earned the city's gratitude, but the absence of a battle prevent him from regaining the standing he lost at Shiloh and kept the defense of Cincinnati from being as celebrated.

Wallace's most notable service came in July 1864 at the Battle of Monocacy in Maryland. Although the forces under his command were defeated by Confederate General Jubal Early, Wallace was able to delay Early's advance toward Washington, D.C. for an entire day. This gave the city defenses time to organize and repel Early, who arrived at Fort Stevens in Washington at around noon on July 11, two days after defeating Wallace at Monocacy.

General Grant relieved Wallace of his command after learning of the defeat of Monocacy, but re-instated him two weeks later. Grant's memoirs of the war praised Wallace's delaying tactics at Monocacy:

If Early had been but one day earlier, he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent. ... General Wallace contributed on this occasion by the defeat of the troops under him, a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory.

Later in the war, Wallace directed the U.S. government's secret efforts to aid Mexico in expelling the French occupation forces which had seized control of their country in 1864.

In 1865 he participated in the military commission trial of the Lincoln assassination conspirators.

He was also involved in the court-martial of Henry Wirz, the commandant in charge of the South's Andersonville prison camp.

|

| Henry Wirz |

|

| “Over the Deadline,” a painting by Lew Wallace based on testimony given at the trial of Andersonville commandant Henry Wirz. |

|

| Wallace's Sketch of Arnold |

During the Lincoln conspiracy trial, Wallace passed the time making sketches of the accused, which he later used as the basis for a large oil painting.

Wallace resigned from the army on November 30, 1865. After the end of the war, Wallace continued to try to help the Mexican army to expel the French and was offered a major general's commission in the Mexican army. Multiple promises by the Mexicans were never fulfilled, and Wallace incurred deep financial debt. Dissatisfied with his careers as a soldier, politician, and lawyer, he began writing in earnest. Wallace published his first novel in 1873.

Wallace resigned from the army on November 30, 1865. After the end of the war, Wallace continued to try to help the Mexican army to expel the French and was offered a major general's commission in the Mexican army. Multiple promises by the Mexicans were never fulfilled, and Wallace incurred deep financial debt. Dissatisfied with his careers as a soldier, politician, and lawyer, he began writing in earnest. Wallace published his first novel in 1873.

As governor, Wallace offered amnesty to many men involved in the Lincoln County War. In the process he met with the outlawed William Henry McCarty, also known as Billy the Kid. On March 17, 1879, the pair arranged that the Kid would act as an informant and testify against others involved in the Lincoln County War, and, it has been claimed, that in return the Kid would be "scot free with a pardon in [his] pocket for all [his] misdeeds." According to this account, Wallace, facing the political forces then ruling New Mexico, was unable to come through on his end of the bargain. The Kid returned to his outlaw ways and killed additional men.

|

| William Henry McCarty, aka "Billy the Kid" |

Inspiration for Wallace’s next second novel came from an unlikely source: his own ignorance. Wallace often told the story of how, on a train trip in 1876, he met the well-known agnostic Colonel Robert Ingersoll, also a veteran of Shiloh.

|

| Robert Ingersoll |

In true lawyer style, he hit the books: First the Bible, and then every reference book about the ancient Middle East he could find. He suspected that a novel about Jesus Christ would be scrutinized by experts, so the plants, birds, clothes, food, buildings, names, places—everything had to be exact. “I examined catalogues of books and maps, and sent for everything likely to be useful. I wrote with a chart always before my eyes—a German publication showing the towns and villages, all sacred places, the heights, the depressions, the passes, trails, and distances.” He traveled to multiple libraries across the country to ensure he had the exact measurements for the workings of a Roman trireme. He provided detail after detail on the design of Persian versus Greek versus Roman chariots. He did everything short of going to Jerusalem himself. Years later, when he actually visited the Holy Land, he tested his research and proudly said, “I find no reason for making a single change in the text of the book.”

He began the book in Indiana, writing in the shade of what would come to be known as the Ben-Hur beech, and finished it in Santa Fe While serving as governor.

|

| Wallace writing under Ben-Hur Beech Tree |

|

| Ben-Hur, A Tale of the Christ |

Ben-Hur became the best-selling American novel of the 19th century, surpassing Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. By 1900 it had been printed in thirty-six English-language editions and translated into twenty others, including Indonesian and Braille. It outsold every book except the Bible until Gone With the Wind came out in 1936, and resurged to the top of the list again in the 1960 when the film version with Charlton Heston was released.

The book has never been out of print and has been adapted for film four times.

|

| Charlton Heston as Ben-Hur |

|

| 1959 Poster for Ben-Hur |

|

| Heston in Chariot Race |

|

| Ramon Novarro as Ben-Hur, 1925 |

The book made Lew Wallace a celebrity, sought out for speaking engagements, political endorsements, and newspaper interviews.

The historian Victor Davis Hanson has argued that the novel drew from Wallace's life, particularly his experiences at Shiloh, and the damage it did to his reputation. The book's main character, Judah Ben-Hur, accidentally causes injury to a high-ranking commander, for which he and his family suffer tribulations and calumny. He first seeks revenge, and then redemption.

In 1884, Century Magazine commissioned a series of firsthand accounts of Civil War battles. With his literary star on the rise, Wallace was asked to contribute one of the first, on Fort Donelson. His article appeared in December, alongside serial installments of Huckleberry Finn and William Dean Howells’ The Rise of Silas Lapham. Whatever satisfaction Wallace took in keeping such august company was soon replaced by apprehension, however, when he learned that Grant, deeply in debt and suffering from cancer, had also agreed to write for the Century series after years of refusing to revisit the war. His subject would be Shiloh. Wallace’s ignominious role in the fight threatened to return to the national stage. Grant wrote an article again stating his belief that Wallace had taken the wrong road on the first day of battle.

Wallace wrote Grant imploring him toa bsolve him of wrongdoing. He also visited Grant to plead with him in person. He arrived on the same day that Twain was paying a call to the former president, bearing an offer to publish his memoirs (and to pay his friend a handsome 70 percent royalty). “There’s many a woman in this land that would like to be in my place,” said Julia Grant when the two callers met in the parlor, “and be able to tell her children that she once sat elbow to elbow with two such great authors as Mark Twain and General Wallace.”

Shortly after the article was published, however, Grant had a change of heart. The widow of a general who had been killed in action at Shiloh had come across a letter from Wallace to her husband, dated April 5, 1862. It was the letter Wallace had sent to the commander of the neighboring division at Shiloh, announcing his plans to use the shunpike should trouble arise. It convinced Grant of what Wallace had long argued. The letter “modifies very materially what I have said, and what has been said by others, about the conduct of General Lew. Wallace at the battle of Shiloh,” Grant wrote. He still maintained that he’d ordered Wallace to take the river road, but allowed that his wishes may have been lost in the fog of war: “My order was verbal, and to a staff officer who was to deliver it to General Wallace, so that I am not competent to say just what order the general actually received.”

Wallace wrote Grant imploring him toa bsolve him of wrongdoing. He also visited Grant to plead with him in person. He arrived on the same day that Twain was paying a call to the former president, bearing an offer to publish his memoirs (and to pay his friend a handsome 70 percent royalty). “There’s many a woman in this land that would like to be in my place,” said Julia Grant when the two callers met in the parlor, “and be able to tell her children that she once sat elbow to elbow with two such great authors as Mark Twain and General Wallace.”

Shortly after the article was published, however, Grant had a change of heart. The widow of a general who had been killed in action at Shiloh had come across a letter from Wallace to her husband, dated April 5, 1862. It was the letter Wallace had sent to the commander of the neighboring division at Shiloh, announcing his plans to use the shunpike should trouble arise. It convinced Grant of what Wallace had long argued. The letter “modifies very materially what I have said, and what has been said by others, about the conduct of General Lew. Wallace at the battle of Shiloh,” Grant wrote. He still maintained that he’d ordered Wallace to take the river road, but allowed that his wishes may have been lost in the fog of war: “My order was verbal, and to a staff officer who was to deliver it to General Wallace, so that I am not competent to say just what order the general actually received.”

It was the vindication Wallace had longed for since 1862. But even this failed to satisfy him. The Century article, with its repetition of the standard account of Wallace’s mistakes, became the Shiloh chapter of Grant’s memoirs. The exoneration appeared as a footnote, one that Wallace worried would be ignored by most readers. Rightly, as it would turn out.

Despite his great fame and fortune from Ben-Hur Wallace lamented, "Shiloh and its slanders! Will the world ever acquit me of them? If I were guilty I would not feel them as keenly."

Wallace had struggled financially through much of his life. His correspondence is full of enthusiastic accounts of railroad investments and mining prospects that never pan out; he patented unprofitable improvements to railway ties, automatic fans, and the fishing rod.

Wallace had struggled financially through much of his life. His correspondence is full of enthusiastic accounts of railroad investments and mining prospects that never pan out; he patented unprofitable improvements to railway ties, automatic fans, and the fishing rod.

|

| James Longstreet |

When Wallace returned from Constantinople four years later, Ben-Hur had become Harper & Brothers’ top-selling title. A steady stream of royalty checks freed Wallace from the practice of law (“that most detestable of occupations,” he called it) and from his creditors. “I contemplate with great satisfaction the pains that will wrench his little pigeon heart when he hears that all my debts are paid,” Wallace wrote of one of them, his brother-in-law.

Wallace enjoyed his newfound wealth. He built the finest luxury apartment building in Indianapolis—the Blacherne, named for an imperial palace in Constantinople—and kept a grand apartment for himself.

“I want a study, a pleasure-house for my soul, where no one could hear me make speeches to myself, and play the violin at midnight if I chose,” he wrote to his wife, Susan, in 1879. “A detached room away from the world and its worries. A place for my old age to rest in and grow reminiscent, fighting the battles of youth over again.”

Wallace designed a writing study, built 1895–1898, near his residence in Crawfordsville, Indiana. A larger-than-life limestone frieze of the face of Judah Ben-Hur—a wholly imagined visage—hovers over the entrance to the study.

Finished in 1898, the building is more castle than study. The grounds once included a moat stocked with fish, until Wallace realized the hazard it posed to neighborhood children and had it filled in.

There is the rocking-chair desk that Wallace fashioned so he could write comfortably outdoors. From his life as a soldier there is a uniform from his 11th Regiment (also known as the Indiana Zouaves), his battle sword, and his lucky buckeye trimmed in silver. Objects from Wallace’s travels, interests, and exploits crowd every available space from floor to ceiling, making this visitor somewhat chagrined by her own lack of industriousness. But the most striking features are the white oak, glass-enclosed bookcases spreading across three sides of the room, still holding Wallace’s personal library. The shelves offer a glimpse into how Wallace spent his free time.

In 1882, five Freemasons decided they wished to see a Shrine organization in Indianapolis. They joined the Shrine Temple at Cincinnati, Ohio, and had that temple's help in establishing an Indianapolis temple. The local organization of the Shrine, called the Indianapolis Shriners, was given its charter on June 4, 1884. The first potentate was John Brush; Lew Wallace Lew was in the first Ceremonial Class, held in 1885. By the end of the first year, there were 105 members. The Murat Temple was built in 1909.

Speaking in 1895 at the dedication of the Chickamauga battlefield, Wallace described the Confederates as having made “an honest mistake.” He encouraged his audience to remember “not the cause, but the heroism it invoked.”

|

| Wallace in his study |

|

| Wallace's Study |

Wallace designed a writing study, built 1895–1898, near his residence in Crawfordsville, Indiana. A larger-than-life limestone frieze of the face of Judah Ben-Hur—a wholly imagined visage—hovers over the entrance to the study.

|

| Face of Judah Ben-Hur over Studay Entrance |

Finished in 1898, the building is more castle than study. The grounds once included a moat stocked with fish, until Wallace realized the hazard it posed to neighborhood children and had it filled in.

|

| Wallace's unfinished painting, The Conspirators |

|

| Murat Shriner's Temple, Indianapolis |

|

| Wallace on cover of Harper's Weekly, 1886 |

Despite using many friends in Washington to influence the government, Wallace's offer in 1898 to raise and lead a division of soldiers for the Spanish-American War was refused; when he attempted to enlist as a private, he was rejected given his age of 71.

There were so many rumors about Wallace’s faith—that he was an atheist or that he had gone to the Holy Land to disprove the existence of Christ—he felt it necessary to introduce his autobiography by dispelling them. He wrote in his autobiography, “In the very beginning, before distractions overtake me, I wish to say that I believe absolutely in the Christian conception of God. As far as it goes, this confession is broad and unqualified, and it ought and would be sufficient were it not that books of mine—Ben-Hur and The Prince of India—have led many persons to speculate concerning my creed. . . . I am not a member of any church or denomination, nor have I ever been. Not that churches are objectionable to me, but simply because my freedom is enjoyable, and I do not think myself good enough to be a communicant.”

|

| Wallace's Carriage |

|

| Zenalda Wallace |

In the days following his death, nearly every newspaper in the country carried an obituary, many of them as lead stories that jumped to full-page spreads. The Cincinnati Enquirer announced the news with a headline overwrought even by fin de siècle standards, though not atypical of the coverage:

Ended

Is the Chariot Race

In Which He Drove Pegasus to Lasting Fame

And General Lew Wallace Succumbs to Death

Author of Ben-Hur Had Hoped to Be Restored

By the Gentler Agencies of Spring

But Failed to Muster the Necessary Strength

To Resist Winter’s Rigor and the Encroachment of Disease—Sketch of His Career

He was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Crawfordsville. Over his grave stands an obelisk draped in a granite rendering of Old Glory. His epitaph is a line taken from Ben-Hur: “I would not give one hour of life as a Soul for a thousand years of life as a man.”

Wallace's last literary work was his own autobiography, published posthumously in 1906.

In 1907, the first fifteen-minute, unauthorized film version was released and Wallace’s son took up the cause, suing the filmmaker for using the plot and title of Ben-Hur without permission of the author’s estate. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court and firmly established the copyright infringement laws for the movie industry that are still in use today.

Wallace's last literary work was his own autobiography, published posthumously in 1906.

In 1907, the first fifteen-minute, unauthorized film version was released and Wallace’s son took up the cause, suing the filmmaker for using the plot and title of Ben-Hur without permission of the author’s estate. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court and firmly established the copyright infringement laws for the movie industry that are still in use today.

|

| Statue of Wallace in National Statuary Hall, Washington, D.C. |

The state of Indiana commissioned a marble statue of Wallace dressed in a military uniform, which was made by the sculptor Andrew O'Connor. It was placed in the National Statuary Hall Collection in 1910. He is the only novelist honored in the hall.

No comments:

Post a Comment