Nellallitea Walker was born in Chicago, Illinois, on April 13, 1891, the daughter of Marie Hanson, a Danish immigrant, and Peter Walker, a West Indian man of predominantly African descent from Saint Croix. Her parents separated shortly after her birth, and he disappeared from their lives.

Her mother was a seamstress and domestic worker. After her mother married Peter Larsen, a Scandinavian, they had another daughter together. Nellie took her stepfather's surname, sometimes using versions of her name spelled as Nellye Larson, Nellie Larsen and, finally, settling on Nella Larsen. When Nella’s younger sister was born, Nella herself was the only visibly black person in her nuclear family. This difficult dynamic was exacerbated by her claim that Peter Larsen was ashamed of his African American stepdaughter.

The mixed family encountered discrimination among the ethnic white immigrants in Chicago of the time.

As a child, Nella lived a few years with her mother's relations in Denmark.

|

| Chicago in the 1890s |

At the age of 16, Nella attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee in 1907-08, where she studied science. The move to Nashville served to distance Nella from her family, something she welcomed because of the shame she had been made to feel during her upbringing. Regarding being seen in public with her family, she said her racial ethnicity “might make it awkward for them, particularly my half-sister.”

She returned to Denmark for four years, and audited classes at the University of Copenhagen. She then came back to the United States.

She was born 26 years after the Civil War ended.

|

| Fisk University |

She was born 26 years after the Civil War ended.

|

| Lincoln Hospital |

In 1914, Larsen enrolled in the nursing school at New York City's Lincoln Hospital and Nursing Home. Founded in the nineteenth century in Manhattan as a nursing home to serve blacks, the hospital elements had grown in importance. The total operation had been relocated to a newly constructed campus in the South Bronx. At the time, the nursing home patients were primarily black; the hospital patients were primarily white; the doctors were male and white; and the nurses and nursing students were female and black.

Upon graduating in 1915, Larsen went South to work at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, where she became head nurse at its hospital and training school. While in Tuskegee, she came in contact with Booker T. Washington's model of education and became disillusioned with it. Added to the poor working conditions for nurses at Tuskegee, Larsen stayed only until 1916.

|

| Tuskegee Institute |

|

| Elmer Imes |

They moved to Harlem in the 1920s. She and her husband knew the NAACP leadership: W.E.B. DuBois, Walter White, Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson and others. She and Imes were socialites, both in Harlem and in white intellectual circles in Greenwich Village. However, because of her mixed parentage, and because she didn't have a college degree, Larsen was alienated from the life of the black middle class, with its emphasis on school and family ties, its fraternities and sororities.

In 1921 Larsen worked nights and weekends as a volunteer with Ernestine Rose, to help prepare for the first exhibit of "Negro art" at the New York Public Library (NYPL). Encouraged by Rose, she became the first black woman to graduate from the NYPL Library School, which was run by Columbia University.

Larsen passed her certification exam in 1923 and spent her first year working at the Seward Park Branch on the Lower East Side, where she had strong support from her white supervisor Alice Keats O'Connor. O'Connor and another branch supervisor where she worked supported Larsen and helped integrate the staff of the branches. She next transferred to the Harlem branch, as she was interested in the cultural excitement in the neighborhood.

|

| Seward Park Branch |

Larsen passed her certification exam in 1923 and spent her first year working at the Seward Park Branch on the Lower East Side, where she had strong support from her white supervisor Alice Keats O'Connor. O'Connor and another branch supervisor where she worked supported Larsen and helped integrate the staff of the branches. She next transferred to the Harlem branch, as she was interested in the cultural excitement in the neighborhood.

|

| Harlem Branch Library |

|

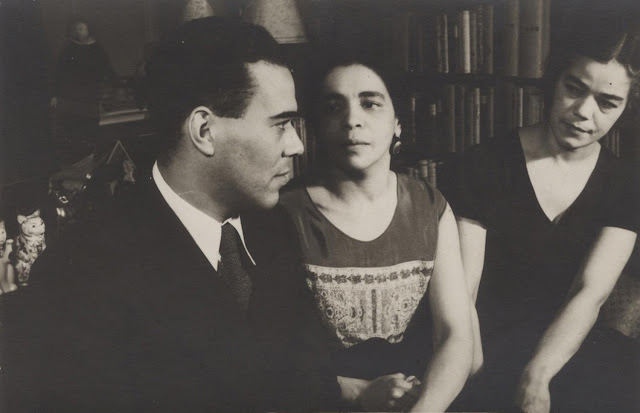

| Larsen |

She became a writer active in the interracial literary and arts community, where she became friends with Carl Van Vechten, a white photographer and writer. Van Vechten introduced Nella Larsen to his publishers, Blanche and Alfred Knopf, who later issued both her novels. Larsen and Van Vechten shared a warm friendship throughout the 1920s, when both were highly visible members of Harlem’s literary community.

|

| Carl Van Vechten |

In 1928, Larsen published Quicksand, a largely autobiographical novel, which received significant critical acclaim, if not financial success. The novel’s main character, Helga Crane, is the daughter of a white mother and black father. She faces hypocrisy and prejudice and her efforts to fit into various white and black communities are unsuccessful.

In 1929, she published Passing, her second novel, which was also critically successful. It dealt with issues related to two mixed-race women who were friends; each had taken different paths of racial identification and marriage. One married a man who identified as black, and the other a white man. The book explored their experiences of coming together again as adults.

Larsen and Imes were having difficulties by the late 1920s. After discovering his ling-term affair with a white woman, she filed for divorce.

In 1930, Larsen published Sanctuary, a short story for which she was accused of plagiarism. It was said to resemble Sheila Kaye-Smith's short story, Mrs. Adis, first published in the United Kingdom in 1919. Kaye-Smith wrote on rural themes, and was very popular in the US. Some critics thought the basic plot of Sanctuary, and some of the descriptions and dialogue, were virtually identical to her work. No plagiarism charges were proved, and Larsen received a Guggenheim Fellowship (the first African-American woman to receive this award) in the aftermath of the criticism.

She used it to travel to Europe for several years, spending time in Mallorca, Spain and Paris, France, where she worked on a novel about a love triangle, in which all the protagonists were white. She never published the book or any other works.

|

| Larsen, 1934 |

Many of her old acquaintances speculated that she, like some of the characters in her fiction, had crossed the color line to "pass" into the white community.

Larsen died in her Brooklyn apartment; her body was discovered on March 30, 1964; it was believed she had been dead about a week. She was 72 years old.

She was buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York.

|

| Nella Larsen's Grave |

No comments:

Post a Comment