James Fisk, Jr. was born in the hamlet of Pownal, Vermont.

He quit school at twelve to assist his father as a travelling peddler, selling housewares and notions. At fifteen he joined Van Amberg’s Mammoth Circus and Menagerie. At 18 he left the circus and resumed the peddling business. By age 21 he was running five wagons throughout New England.

He was 26 years old when the Civil War began.

|

| Washington, D.C. during the Civil War |

|

| Daniel Drew |

|

| Cartoon of Vanderbilt and Fisk |

|

| Jay Gould |

|

| William "Boss" Tweed |

She was an unemployed actress and a friend of Miss Wood. At the time Josie only owned one passable dress and her rent was overdue.

Though Jim Fisk had a wife back in Vermont, he was smitten by the girl, and not only paid her rent, but also provided her with finery. Josie Mansfield was considered extraordinarily beautiful. After meeting Jim Fisk, Josie gave up any attempt at acting.

Fisk and Gould created "The Gold Ring" in an attempt to corner the gold market; it culminated in the fateful Black Friday of September 24, 1869. Starting on September 20, Gould and Fisk had started to buy as much gold as they could. Just as they planned, the price went higher. Fisk's and Gould's effort collapsed when President U.S. Grant intervened to halt the Black Friday Panic. Then the price of gold plummeted, and investors scrambled to sell their holdings. Many investors had obtained loans to buy their gold. With no money to repay the loans, they were ruined. Gould escaped disaster by selling his gold before the market began to fall.

|

| Josie Mansfield |

Fisk and Gould created "The Gold Ring" in an attempt to corner the gold market; it culminated in the fateful Black Friday of September 24, 1869. Starting on September 20, Gould and Fisk had started to buy as much gold as they could. Just as they planned, the price went higher. Fisk's and Gould's effort collapsed when President U.S. Grant intervened to halt the Black Friday Panic. Then the price of gold plummeted, and investors scrambled to sell their holdings. Many investors had obtained loans to buy their gold. With no money to repay the loans, they were ruined. Gould escaped disaster by selling his gold before the market began to fall.

|

| September 24, 1869 - "Black Friday" |

Fisk was vilified by high society for his amoral and eccentric ways and by many pundits of the day for his business dealings; but he was loved by the workingmen of New York and the Erie Railroad.

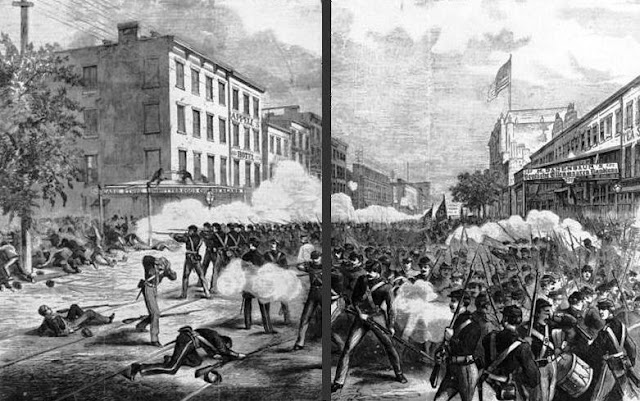

Fisk was vilified by high society for his amoral and eccentric ways and by many pundits of the day for his business dealings; but he was loved by the workingmen of New York and the Erie Railroad. He was known as "Colonel" for being the nominal commander of the 9th New York National Guard Infantry Regiment, although his only experience of military action with this unit was an inglorious role in the Orange Riot of July 12, 1871. The Orange Riots took place in Manhattan in 1870 and 1871, and involved violent conflict between Irish Protestants, called "Orangemen", and Irish Catholics, along with the New York City Police Department and the New York State National Guard.

|

| The Orange Riot of July 12, 1871 |

The riot caused the deaths of over 60 civilians, mostly Irish laborers, and three Guardsmen. Over 150 people were wounded, including 22 militiamen, 20-some policeman injured by thrown missiles and 4 who were shot, but not fatally. About 100 people were arrested.

|

| Edward Stokes |

|

| Josie Mansfield |

In a bid for money, Mansfield and Stokes tried to extort money from Fisk by threatening the publication of letters written by Fisk to Mansfield that allegedly proved Fisk's legal wrongdoings. A legal and public relations battle followed, but Fisk refused to pay Mansfield anything.

|

| Grand Central Hotel, New York City |

Stokes fired two shots at Fisk from a Colt pistol, one to the abdomen and one to the left arm. Stokes tried to flee but was captured.

Fisk gave a dying declaration identifying Stokes as the killer. He was 36 years old when he died.

|

| "He Never Went Back on the Poor" |

His coffin lay in state for a day at the Grand Opera House in New York City, the theater that he had owned and managed. More than twenty thousand people passed by to pay their respects and more than a hundred thousand more stood in the street.

Fisk was buried in the Prospect Hill Cemetery in Bratteboro.

The Fisk monument, created by sculptor Larkin G. Mead, has in a circle at its base four young women. Each of the women holds one of the following: a sack of coins, railway shares, steamship holdings, and an emblem of Fisk's patronage of the theater.

|

| Fisk Monument, Battlebro, Vermont |

The trial resulted in a hung jury—at least one juror was suspected of being bribed.

At his second trial Stokes was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to be hanged, but the verdict was overturned on appeal.

At his second trial Stokes was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to be hanged, but the verdict was overturned on appeal.

In his third trial Stokes was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to six years at Sing Sing Prison.

Josie Mansfield left New York for Paris, France where she married Robert L. Read, an expatriate American lawyer. When he died, she moved to Boston; then in 1899, in failing health, to Philadelphia to live with her sister. In 1909, in dire poverty, she moved with a brother to Watertown, South Dakota. Somehow she returned to Paris where she lived for many years. Josie died in 1931 at the American Hospital in Paris.

Edward Stokes served four years of a six-year prison sentence for manslaughter.

No comments:

Post a Comment